Like the old adage goes: Careful what you wish for.

In 2001 and 2002, the softwood lumber and steel industries pleaded for the Bush administration to protect them from foreign imports that were ruining their respective businesses. Both got their wish. But each has experienced varying degrees of relief, and much of the hope and hand-wringing over protective trade measures never really made it out of Pandora's box.

For example, businesses that use steel and softwood lumber were adamant about the negative effect on their companies, and some fears have certainly been realized. However, on the whole, they appear less than advertised. Nor have the protective measures been a boon to the targeted industries. Indeed, the protective measures on softwood lumber imports have compounded the woes of the U.S. industry.

For steel, it appears that neither the greatest fears nor hopes will be realized by either steel makers or users. According to a January 2003 report by Gary Hufbauer and Ben Goodrich of the International Institute of Economics (IIE), U.S. steel policy "has not been nearly as helpful to the U.S. steel industry as partisans hoped. At the same time, it is not nearly as bad as some steel consumers and foreign exporters may have feared."

A protective primer

While the steel and softwood lumber industries came to be protected by different routes and are protected by different trade measures, they share many basic traits. Both industries faced a surge of foreign imports in the late 1990s through the early part of the new millennium, which pushed down prices and made life miserable for U.S. firms. Both industries sought, and received, government protection in the form of surcharges on imports (either duties or tariffs, which are technically different but, in practice, have the same effect) from certain countries believed to be the biggest source of import problems.

For softwood lumber, the U.S. Department of Commerce ruled in 2001 that Canadian exports to this country were being subsidized by the Canadian government and that sawmills there were selling lumber at below-market prices (called dumping in trade lingo). As a consequence, the federal government enforced so-called countervailing and anti-dumping duties—in essence, import taxes paid to the U.S. government—totaling 32 percent starting in May 2001. After further investigation, the duty was finalized at 27 percent and became effective in May 2002.

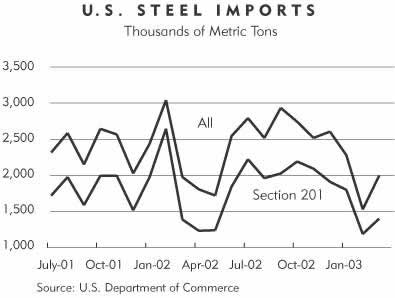

The steel industry, on the other hand, was in effect given a "time out" from harsh foreign competition. Though steel imports were not found to be subsidized or dumped in the U.S. market, the Bush administration enacted "safeguard" provisions (under Section 201 of the 1974 Trade Act) and imposed tariffs of up to 30 percent on a host of steel imports starting in March 2002.

One major difference between the protective measures of the two industries is their duration. Steel safeguard measures have an initial expiration date of three years, though they can be reapproved. Softwood lumber duties remain in effect until such time as Canadian imports are not subsidized by government or dumped by firms—though each government has a different interpretation of subsidies and dumping—or until the countries reach a mutual agreement on corrective action. In both cases, protective measures are being hotly contested by the foreign countries affected.

You should see the other guy

The net result of these trade protections is, at best, mixed. By many accounts, tariffs against steel imports have helped the domestic steel industry. But that doesn't mean the benefits have been evenly spread, even among steel producers. Domestic steel production is split roughly in half between integrated (or blast furnace) mills and the newer-generation mini-mills (or electric arc furnace). Integrated steel mills make almost all flat-rolled steel—sheet- or plate-like final products that manufacturers twist and mold into other goods like cars and appliances. About one-third of the production of minimills is flat-rolled steel, and the other two-thirds is made up of so-called long products—rebar, structural steel (like girders), wire rod and the like.

That distinction is important, because when it comes to the tariffs, "the difference lies not in total production, but in the products [each] makes," according to Thomas Danjczek, president of the Steel Manufacturers Association (SMA), a minimill industry group.

Rather than a uniform tariff across all steel imports, the Bush administration levied sliding-scale tariffs based on perceived pressures from imports. As a result, "the benefits of Section 201 disproportionately favored flat-rolled production" because they were hit harder by imports, Danjczek said. Producers of long products were supposedly hurt less by imports, and where tariffs were imposed, they tended to be smaller than tariffs imposed for flat-rolled products.

As such, the tariffs offer integrated mills more protection from imports. According to data from Commerce, imports of Section 201 products declined by about 2.2 million metric tons from 2001 to 2002. However, imports of flat-rolled products alone—the main product of integrated mills—decreased by 3 million metric tons, meaning that cumulative imports of all other "protected" steel products actually increased.

Trade protections also create exaggerated scapegoats, conveniently deflecting attention away from sources of domestic competition. With higher average production costs, integrated steel producers and their unionized workforces "concentrate their blame on imports, [but] over half of the decline in traditional integrated steel production is attributable to the rise of domestic minimills," like giants Nucor and Steel Dynamics, according to Hufbauer and Goodrich.

Danjczek acknowledged that minimills are in comparatively better financial shape than most integrated mills thanks to newer technology, nonunion labor and few of the burdensome retirement and other legacy costs of integrated steel mills. But the minimill sector is also struggling to compete with cheap imports and other pressures—evident in the fact that it has seen twice the number of bankruptcies as integrated mills over the last four years or so. "There's no solace in being the healthiest patient in the cancer ward," Danjczek said.

[The Bush administration also placed more than 1,000 individual steel products—most of them small-volume niche products-on an "exclusion" list that exempted these imports from any tariff. The rationale is that these customized products have little or no domestic competition and would not threaten the safeguard intentions of the tariffs. The full effect of these exclusions on either steel-making or steel-consuming firms, however, is complicated and not addressed in this article.]

Softwood: Is there a do-over button?

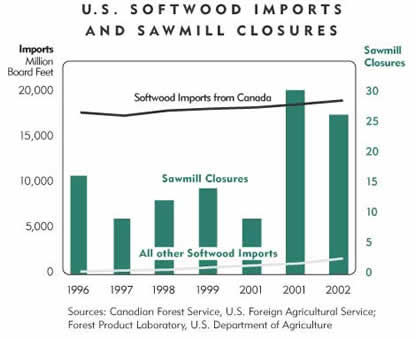

By most assessments, the softwood lumber protections have actually backfired, particularly in the short term. The domestic industry pleaded for protection from Canadian imports, whose low costs were forcing dozens of sawmill closures across the country. Between 1996 and 2000, there were 60 softwood sawmill closures in the United States, according to research by Henry Spelter of the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wis.

But the hardest years were yet to come in 2001 and 2002, when the duties on Canadian softwood lumber imports were first introduced and later finalized. In just those two years, 56 U.S. softwood mills got shuttered, according to Spelter. Through the first three months of this year, there have been at least three closures of U.S. sawmills, including one in Libby, Mont., along with temporary production curtailments at about 20 other mills, according to Spelter, Random Lengths (an industry newsletter) and other sources. Spelter estimated that more than 4,000 (net) U.S. sawmill jobs have been lost since 2001.

In the district, Montana has easily the largest softwood lumber industry with 26 sawmills and capacity of almost 3 million cubic meters. It added one mill—North End Timber in Olney—but saw at least eight mills close from 1995 to early 2003, according to industry tracking by Spelter. Minnesota has seen only one closure among its 10 sawmills since 2001, and today has a capacity of about 420,000 cubic meters.

Four of Wisconsin's nine sawmills are located in the district, with a capacity of almost 500,000 cubic meters, and there have been no closures or openings since at least 1995, according to Spelter. The Upper Peninsula of Michigan has five mostly small mills with a capacity of almost 400,000 cubic meters, more than three-quarters of which comes from a new Louisiana Pacific plant opened about five years ago in Gwinn. The Dakotas have no softwood lumber industry.

The reason for the widespread U.S. closures was simple, albeit counterintuitive to the expected effect of the import duties. Rather than close down mills in Canada because of the increased cost, Canadian sawmills went into overdrive and ramped up production, increasing annual softwood production in 2002 by almost 5 percent and pushing 2 percent more exports into the United States, despite the 27 percent duties, according to data from the Canadian Forest Service (see chart below).

There were two underlying motivations for higher Canadian production, according to a number of sources. The first was that sawmills were looking to lower their unit costs enough so they could internally absorb part of the 27 percent duty. By lowering their unit costs through economies of scale, firms were also hoping that subsequent Commerce administrative reviews of the duties would show that Canadian firms were not dumping wood illegally into the U.S. market, according to Susan Phelps, an economist with the Canadian Forest Service.

One industry consultant, asking to remain unnamed for fear of retribution from clients, said that motivation is half right, but all wrong. "There is always the incentive to lower the cost of production," he said. Canadian mills can and will lower their unit costs by going full throttle on production, but only incrementally. In the end, it's a failed strategy, both for mills and for the industry.

"By increasing production you can affect prices much more than cost. You can lower your variable cost some, but not that much," the source said. The subsequent increase in softwood supply puts faster downward pressure on prices than it does on a company's cost structure. "In the long run it's not an effective strategy."

The second, and related, motivation for higher production amounts to a trade game of chicken between the Canadian industry and U.S. regulators. Canadian mill owners believe that U.S. softwood duties eventually will be deemed illegal by the World Trade Organization (WTO), which arbitrates such international trade disputes, and then rescinded by the United States. If that happened, all or part of previous duties paid might be retroactively returned to sawmills. However, if the duties are not overturned, or if prices don't rebound for other reasons, said the industry source, "you'll see production screech to a halt in Canada."

Trickle up, down economics

Analyzing the effects of trade protection also demands a look outside the targeted industries, to upstream raw material suppliers and downstream users and sellers of steel and lumber goods. Combined, there are literally tens of thousands of businesses involved in processing raw materials into finished products for each industry, and determining benefits or harm at the firm level is virtually impossible because numerous factors contribute to a firm's profitability (or lack thereof), including trade measures.

However, for steel, it is fairly safe to say that some upstream raw material suppliers have been helped. The taconite mines of northern Minnesota and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, which send all of their production to integrated steel firms, celebrated the tariffs. "The tariffs have had a [beneficial impact] primarily on our customers, the integrated steel mills," said Frank Ongaro, president of the Minnesota Iron Mining Association. "The tariffs are doing what they are supposed to be doing" by allowing the steel industry to reorganize and become more competitive, which in turn "will provide some certainty in demand for our product."

Still, the taconite industry remains in tenuous condition. In May, EvTac Mining closed down mine operations in Eveleth, Minn., idling 450 workers. It also forced the layoff of about 80 employees by a local railroad company that hauls crude taconite to processing plants, and then takes finished pellets to Duluth Harbor for transport to integrated steel plants along the Great Lakes.

In fact, the taconite industry was seeking more help than it ultimately received. It lobbied for additional tariffs on unfinished slab imports that integrated steel companies can use in their blast furnaces in place of taconite pellets. "We believed [a tariff on unfinished slab] would have been directly beneficial to the taconite industry," Ongaro said. But rather than a tariff on the first ton imported, the Bush administration placed a tariff quota on unfinished slab, whereby tariffs don't kick in unless imports exceed normal levels.

The tariff effect on downstream steel users is more difficult to pinpoint. Prices spiked shortly after tariffs were imposed, which had a chilling effect for manufacturers. In testimony last year before the House Committee on Small Business, Erick Ajax of E.J. Ajax and Sons of Fridley, Minn., said that steel tariffs have "undermined our competitiveness." The firm is a three-generation family business that makes hinges and other steel parts for appliances and electrical enclosures.

Ajax told committee members that most of the firm's long-term contracts to buy steel were broken shortly after the tariffs were imposed, which forced the company to buy in spot markets, which increased their cost for raw steel by 30 percent to 60 percent, and also extended lead times from days to months. The company lost several clients, and within six months after the tariffs were imposed, Ajax laid off 20 percent of its workforce.

But monthly surveys of steel-using manufacturers by the American Institute for International Steel (AIIS) show that booking prices for most major products dropped considerably after the initial spike, and buyers of hot- and cold-rolled steel were looking at a moderate oversupply of steel through the first quarter of this year.

For softwood lumber, most firms throughout the supply chain are hurting because of Canada's production push. "Overall, we haven't seen any significant change here," said Doug Dennee, a buyer for Lake States Lumber in Aitkin, Minn., a lumber distribution center with $100 million in sales with outlets also in Osseo, Minn., and Sparta and Schofield in Wisconsin. The firm is also building a large wood treatment plant in Duluth.

Dennee said the company was hoping the duties would push up low lumber prices because the company makes its money based on price margins, rather than lumber volume. As prices increase, so too does their fixed margin; the opposite happens as prices decrease. But with the exception of a brief price spike in 2001, prices have remained low since import duties were imposed. So despite record demand, "we're barely scraping by working on small margins. It's not a pretty industry," Dennee said.

Given low lumber prices, one might think that manufacturers of component wood products are enjoying the softwood duties. Not so. The Wood Truss Council of America reported in a December policy report that a two-tier pricing system has evolved, whereby Canadian component manufacturers pay a lower (nonduty) price for their lumber. Raw lumber can constitute up to 50 percent of the cost of a manufactured component like a truss (used in roof framing), and there are currently no import duties on manufactured wood products. As a result, Canadian firms can "sell manufactured components in U.S. markets at much lower prices."

Win, lose or drawing unemployment

Much of the discussion of the winners and losers in these trade measures focuses on jobs. Finding anecdotes to fill out an argument is easy, but figuring out what they cumulatively say about the efficacy of trade protection is not.

Steel-using manufacturers, like Ajax, said the protections would push up their input costs and cause massive layoffs. The data seem to suggest as much: Transportation equipment and fabricated metal sectors both lost at least 5,000 jobs in Wisconsin alone from 2000 to 2002, while the industrial machinery sector there lost closer to 15,000, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

But a jobs barometer can be very misleading. For starters, the exact role of trade protection in jobs that are either saved or lost is largely unknown; there are many other economic factors to weigh in a company's profitability, including the strength of domestic and world economies. Nonetheless, jobs that are saved or lost are often entirely attributed to trade protections.

Several studies have attempted to put a finer point on the cost of steel tariffs in terms of jobs, but most are based on economic modeling. A study for the Consuming Industries Trade Action Coalition put the job-loss figure among steel-consuming firms at between 15,000 and 50,000. In contrast, reports by Peter Morici of the University of Maryland and the American Iron and Steel Institute reported employment in steel-intensive industries has actually grown.

But almost no one has done the tedious legwork of aggregating net job losses or gains at various sector levels (much less throughout the processing chain from raw material to finished good) and determined a more precise effect of tariffs and duties. Spelter's tracking of sawmill closings is unique in its thoroughness and timeliness of that particular sector, and even he concedes it has shortcomings. Hufbauer and Goodrich of the IIE acknowledged that "analysts can only make educated guesses as to the magnitude of worker layoffs."

In fact, so little concrete information is available regarding the impact of tariffs on steel-consuming industries that the House Ways and Means Committee sent the International Trade Commission on a fact-finding mission to answer this and other data questions. That report is due out by the end of September.

Show me the money

In the long run, with or without future protections, U.S. producers of steel and softwood lumber are likely to struggle unless they can rein in a simple problem: too much unprofitable capacity. Count all the jobs you want—at the end of the day, profits are the only thing that can keep firms alive and employees working, save lifelong government intervention. And while consolidation has been under way for the steel and softwood lumber industries, neither has seen much capacity permanently shuttered. That's not bad if profits remain healthy, but that hasn't been the case, and trade protections are more likely to exacerbate the situation.

Isolating the effects of softwood lumber duties on U.S. firm profits is difficult because the largest companies are conglomerates that produce many different wood products, including lumber. With that caveat, profits for the 31 largest U.S. forestry and paper firms dropped from $7 billion in 1999 to $1.5 billion by 2001, with 12 companies reporting losses, according to the Global Forest and Paper Industry group at PricewaterhouseCoopers. Annual figures for 2002 were not available, but through the first quarter of 2003, the seven largest U.S.-based forest and paper firms saw their net earnings drop 59 percent over the same period a year earlier.

For the steel industry, 34 producers have filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy since 1999, according to a January 2003 report to the SMA board of directors. But so far, profitability has not returned to the steel industry because only a small amount of domestic and international capacity has been permanently closed down, particularly among integrated steel mills, which generally have higher costs per ton than minimills. With slackening demand from slow U.S. and world economies, prices have generally been low, except for a brief spike when the tariffs were first imposed.

Hufbauer and Goodrich from the IIE point out that the steel-making industry is likely to take an after-tax loss for 2002, despite the Section 201 safeguards. But a closer look by the authors at SEC filings found that profit margins for the minimill industry have been in the black for the last eight years (though 2001 was particularly lean), while the integrated industry has been in the red for the past four years.

The problem of unprofitable capacity is very much a global issue. The excess capacity wrung out of U.S. steel mills will be more than offset by the growth in Chinese capacity alone, with far higher costs per ton. The steel safeguards, according to Danjczek of the SMA, amount to "a 5- to 6-ton solution to a 30-ton problem." At the end of the three-year safeguarding period, "the [U.S.] industry will be better off, but the core capacity issue will not have been addressed. ... There are too many [steel] tons chasing too few orders."

The domestic steel industry is also very fragmented for a mature industry, with the top four global steel firms holding only 15 percent of the market. "There are some who will tell you we have a long way to go" regarding consolidation, Danjczek said.

An (almost) empty winner's circle

By rights, the softwood lumber industry should not be looking at the same problem regarding profits. U.S. softwood lumber consumption hit a record 56 billion board feet last year, most of which was used for structural framing in houses, and 19 billion was imported from Canada, also a record.

But strong demand has not managed to budge prices much. Prices did spike to over $400 per thousand board feet in May 2001—which are high, but well off record highs-in anticipation of the duties imposed later that year. Since then, however, average softwood prices have dropped and stayed low and relatively stable.

That's because sawmill capacity continues to grow in spite of the duties, the closures and the low prices, which in turn has pumped up supply. Dennee of Lake States Lumber said that without a hot home-building market pushing record lumber demand, "we'd have really seen some ugly prices."

Spelter, from the Forest Products Lab, points out in a report earlier this year that while some capacity shuts down in lean times, often it is brought back online later. At the same time, profitable sawmills increase capacity to take better advantage of economies of scale. From 1996 to 2002, the buzz of 15 new mills came online in the United States along with numerous plant expansions. So, despite the carnage wrought by more than 100 mill closures in the United States during those seven years, the U.S. industry expanded by more than 6 million cubic meters, or almost 8 percent. Canadian capacity during this time grew almost 12 million cubic meters, or 17 percent.

In the final tally, Dennee sees few winners in the softwood controversy, save one. "The only one that's winning is the guy building his house. Did the Canadian mills win? No. Did U.S. mills win? No. Wholesaler? No. Retailer? No. Only the home buyer won."

Many believe trade protections have only postponed the inevitable. In a late January 2003 speech, David Phelps, president of the AIIS, said that "trade protection would only delay restructuring, and the weak companies would return to the bad habits that made them weak. The strong companies, on the other hand, do not need the protection in the first place."

For the last three-plus decades, the steel industry has been among the most frequent user of trade protection, all "in the name of averting layoffs and restoring the industry to financial health," according to the IIE's Hufbauer and Goodrich. "If trade protection could foster industrial prosperity, the U.S. steel industry would be doing very well."

Wooden psyche

Ultimately, the supply and profitability problem is not likely to go away unless governments stop their habit of helping struggling firms. But that's a difficult hurdle, even in the United States, because these are mature industries and their downfall is particularly visible at the local level.

Forests, for example, have played a vital role in the Canadian psyche. Almost half of the country is forested, and its 418 million hectares of forest represents 10 percent of the world's supply. Forests are considered a national asset—90 percent are owned by the crown—and are managed and harvested as a social contract of sorts between firms, workers, communities and government.

In fact, Canadian appurtenances—minority property rights or privileges—"require a company to run a manufacturing facility as a condition of their tenure," and also establish minimum cutting requirements to keep the mill in operation, according to Brian Payne, president of Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada. In a union press release, Payne said a U.S. Commerce proposal to change the Canadian pricing system to a market-based auction system (like in the United States) would "throw away more than a half a century of public policy which connects the right to harvest timber to an obligation to provide employment and community stability."

The Council of Forest Industries, the "provincial voice" of the British Columbia forest industry, reports that 31 local areas, containing 270 communities, depend on forest activity, for more than 20 percent of the area's income. In Quebec, forest resources provide 100 percent of manufacturing jobs in 135 towns and villages, according to AMBSQ, the regional forest industry association.

As such, regardless of prices or supply, Canada is going to cut some softwood and a majority of that production will get exported, most likely to the United States, and the government has shown interest in helping the industry survive whatever the price. The government has already approved about $340 million to support the health of people and communities whose livelihood depends on softwood lumber.

Some Canadian officials have even called for make-work measures to keep the industry spinning. In a letter to the Canadian Minister of Foreign Trade, Payne said the country "should take exceptional measures to increase Canadian demand for lumber by funding a nonprofit housing and renovation program."

Dennee acknowledged the social dilemma. "That [Canadian] town is dependent on that sawmill ... so it's not that easy to turn out the lights" on the mill and, by extension, the town. "The [Canadian] mills are very reluctant to do that."

"Ride it out"

Economic theory would have predicted—or at least not been surprised by—much of what has transpired in either industry. Economists often rail against trade protections as wasteful because they artificially and inefficiently restrict choice, and in the process they distort markets.

Advocates of trade protection point out that such measures help level the international playing field—that U.S. firms cannot be expected to compete against heavily subsidized foreign competitors. Maybe, if you're talking about some moral notion of fairness. But in a broad financial sense, it's actually good business to let other countries subsidize your consumption.

Though it's counterintuitive to the typical political response for help, the loser in the business subsidies war is the country doing the subsidizing, because it transfers tax dollars (which buy down the price of exported goods) to the country where those goods are purchased. If Canadian subsidies lower the lumber costs for a new house in the United States by say, $500, that's a direct transfer of dollars (or other assets) from Canadian taxpayers to U.S. homeowners.

Canada might have a big lumber industry, but to pay for lumber subsidies, it has to raise taxes on other industries or sell off scarce forest resources at below-market value. The winner is the United States; while it might lose lumber-producing jobs, homeowners will have $500 to invest or spend elsewhere, which will create jobs in other industries.

* Weighted average of 15 key framing lumber prices. Source: Random Lengths |

| March 31, 2001: Expiration of Softwood Lumber Agreement. August 2001: Commerce levies 19.3% preliminary coutervailing duty against Canadian softwood lumber, declared retroactive to May 19 due to evidence of impact surge. October 2001: Commerce issues preliminary ruling implementing an additional 12.6% anti-dumping duty on Canadian softwood imports. April 2002: Commerce lowers final duties on Canadian softwood imports to 27.2%; Commerce also rules that lumber imports "threaten" rather than cause injury to the U.S. industry, thereby forgiving all bonds posted on Canadian softwood lumber imports during the previous year. May 22, 2002: Enforcement of duty begins; there are rampant anecdotes about increased Canadian shipments prior to this date. Total shipments through April 2002 are up 7% over previous year and set a new record for that period. January 2003: Commerce presents Canadian officials with a proposed solution for eliminating the duties and asks provinces to adopt auctions and other market-based pricing practices used in the United States. Canadian officials reject the proposal, in part because it would end minimum cutting requirements that keep many mills in small communities in business. |

Protective trade measures, in essence, ask foreign countries to stop subsidizing our consumers. Such measures remain popular because they offer immediate and direct help to a particular industry and its workers. The pain of these measures is redistributed and diffused upstream and downstream, where cumulative effects can be harder to discern.

Other political realities also influence the crafting of trade protections. In the case of steel tariffs, Hufbauer and Goodrich say they "were driven not by an economic match between problems and solutions but by two political motivations." The first was the "noble" intent of passing the Trade Promotion Authority, which they described as a "one step back, two steps forward" approach to liberalizing free trade; the second motivation was a "less noble goal of buying the steel industry's support in congressional and presidential elections."

The administration also tiptoed its political way through steel exclusions. Along with the 1,000-plus product exclusions, imports from more than 100 different (mostly developing) countries were also excluded from tariffs, including Latin and South American countries the administration is courting in a hemispheric trade pact called the Free Trade Area of the Americas.

But this political nit-picking can backfire. For example, formal objections to steel safeguards from foreign countries rose almost sixfold in just the first nine months of 2002 compared with all of 2001. More importantly, it has dampened negotiations to cut global steel capacity among major producing countries.

For the moment, these trade protections are a matter for the WTO. But regardless of the WTO's position, unfavorable rulings can be mitigated by either party through time-consuming appeals, or by narrowly interpreting the decision. In the softwood debate, WTO rulings in November and March had both sides claiming victory because each found sections that supported its viewpoint in the controversy.

In late March, a WTO panel issued a negative ruling on the legality of the Section 201 steel remedy, but it is unlikely to have much impact. The WTO has similarly ruled against the United States in other cases of steel safeguards, but none has led to a repeal of tariffs or quotas in question. What's more, any negotiating period between the WTO and affected parties to end the current tariffs would likely extend beyond the safeguard's remaining time of less than two years.

While trade protection is hotly debated in Washington and elsewhere, firms outside the Beltway often decide it's not worth holding their breath. Joe Lind operates a sawmill—"we're kind of a one-horse outfit"—in Hysham, Mont., located in the lower eastern half of the state. In this case, he's the horse, with occasional help from his sons and others when he needs it. He custom cuts about 1,000 "rough and green" board feet a day, mostly to maintain local ranches. He gets his logs from private timber stands because he can't compete with the big sawmills in public forest auctions.

Regarding the duties on Canadian softwood, "I don't see that it's had much effect. ... There seems to be a lot of lumber going through [his area] from the north," Lind said. Cheap lumber will always be popular "as long as people can get it, and I don't blame them. That's business," Lind said. "I don't think there's anything you can do about it but ride it out."

See earlier fedgazette articles on both the softwood and steel industries.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.