Many images might come to mind when you hear the word "organic." Perhaps it's that friendly farmer who sells you tomatoes every summer. Or maybe it's the free-range chicken you buy once a week at your neighborhood co-op. Or it could be the expanding natural foods aisle at your local supermarket.

Whatever the case, with U.S. sales of $7.8 billion in 2000 and projections of nearly $20 billion by 2005, it's more than healthy eaters taking notice. More farmers see the industry as a way to diversify and to protect against the low-price spiral plaguing traditional operations, and federal and state governments are just starting to recognize and help the organic farming industry.

Following the passage of the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) developed a set of standards that products must meet to wear the official "organic" label. For example, products must be grown in soil that has been free of prohibited substances for at least three years; pest control must depend on biological diversity instead of synthetic pesticides or fertilizers. And there are accreditation agencies and organizations throughout the country to verify producers' growing and handling procedures.

Still considered a niche farm industry, there is very little data on organics—which some consider ironic given the vast research networks of the USDA and literally hundreds of other ag-based research groups, from crop associations to land grant universities.

The most reliable, comprehensive source—the USDA's Agricultural Census—was last conducted in 1997. While the state of the industry has likely changed significantly over the last five years, it is safe to say that organic products are grown or raised on a very small proportion of farmland—only 0.2 percent, or 1.3 million acres, were certified pasture or cropland in 1997.

But consumer demand has been on the rise for over a decade and is expected to continue, fueled by increasing concern with health issues and an ever-growing variety of processed organic products ranging from frozen dinners to soft drinks. According the Economic Research Service (ERS) of the USDA, the number of U.S. certified organic farmers grew 40 percent between 1992 and 1997 to a total of 5,021 growers, while organic acreage increased 44 percent to 1.3 million acres. Packaged Facts, a marketing research firm, reports that sales for organic products had a compounded annual growth rate of 22 percent from 1996 to 2000.

Strong demand for organic products, coupled with the fact that they are also more labor and resource intensive than conventional farm products, has translated into premium prices. According to a study conducted by researchers from South Dakota State University, price premiums for common Midwestern organic crops like soybeans and corn can range as high as more than double that of their conventional counterparts. For example, in 1999 organic soybean prices averaged 117 percent higher than conventional soybeans, and in 2000 were 175 percent higher.

Ron Desens of Litchfield, Minn., depends on that price premium. A farmer of about 300 organic acres of soybeans, oats, hay, pasture, cattle and broilers, Desens said, "I just don't think a small [conventional] farm could support our family."

Given strong demand, high prices and potential profits, the main question might be why more farmers haven't "gone organic." The answer appears to be part financial and part cultural, and complemented by a lack of information and research support on organic farming demand, techniques and marketing strategies.

Source: Economic Research Service, U.S. Department

of Agriculture

Down on the organic farm

An organic farm is probably the closest thing that farm advocates will ever get to a return of the small farm. According to a 1997 report from the Organic Farming Research Foundation (OFRF), the majority of U.S. organic farms were family operations, averaging about 140 acres compared with full-time conventional farms in the district that often run in the thousands of acres. For example, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture reported that in 2000 the majority of state organic farmers had fewer than 250 acres.

Despite the premium prices, organic farming is not a cash cow, at least not for most. About half of organic farmers grossed less than $15,000 per year, while 34 percent grossed anywhere from $15,000 to $100,000 yearly. According to the USDA, overall agricultural output in 2000 reached slightly over $100,000 per farm.

One major hurdle facing organic farmers is finding the right place to sell their products. "We go to a farmers' market every week and sell about two tons of organic hay a year to a horse farmer," says Desens, whose farm is about 65 miles from the Twin Cities. "It's easier to sell in metro areas, and you get a higher price."

But while direct marketing offers the advantage of cutting out the middleman and offering higher profit margins, the communications and marketing expertise necessary can be daunting to many farmers. A 1997 OFRF survey of organic farmers found that 80 percent of organic goods were marketed to wholesalers rather than to retailers or consumers.

Packaged Facts estimates that a mere 3 percent of total organic sales were from direct markets in 2000—although that's roughly twice the level of conventional farms—while 49 percent of organic sales came from mass market outlets, such as traditional supermarkets and drugstores. Another 31 percent came from natural foods supermarkets like the Whole Foods chain, which currently amasses nearly $2 billion in annual sales in 117 stores nationwide and expects to reach $4 billion by 2003.

Interviews with organic farmers in the Ninth District reveal that most do the bulk of the work themselves, sometimes with the aid of family members or temporary workers, especially at harvest times. Oftentimes farmers take over their family's conventional farm and gradually make the shift to an organic system afterward. Dennis Schill of Hannah, N.D., began operating his family's farm in 1985, and now runs a mostly organic operation of 640 acres of grassland, hay, trees and conservation acres, in addition to raising sheep and broilers.

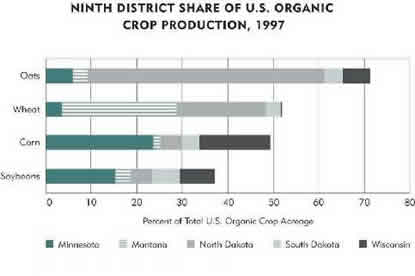

In fact, Ninth District states have a strong presence in organic farming, with Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota and Montana all ranked in the top six in the nation for certified organic acreage as of 1997, and South Dakota ranked 11th (see table below).

North Dakota, for example, was the nation's leader in acreage for organic oats, millet, rye and total organic grain production. It was also the leader in organic flax and sunflowers, maintaining almost 12,000 acres, or about 60 percent of the U.S. total. Montana was the second highest producer of total grain and the leading producer of organic wheat (nearly 32,000 acres). Minnesota was second in organic soybeans, fourth in corn. It also grew nearly half of the nation's buckwheat and had the third highest number of organic milk cows, behind Wisconsin. Much like conventional farming, district organic farmers harvested almost no fruits or vegetables.

Support group for organic hurdlers

New organic farmers face many obstacles when starting out. "In the beginning, the biggest problem is your own lack of experience," said Robert Quinn, an organic farmer of 3,000 total acres rotated between winter wheat, kamut wheat, alfalfa and various other crops in Big Sandy, Mont. That sentiment was echoed by Schill, who mentions a high "learning curve" that new organic farmers must climb.

And there are other hurdles. For example, to grow certified organic produce, soil must be kept free of banned synthetic materials for three years prior to certification. Doing so leaves both crops and farmers in a "premium limbo" between organic and conventional prices.

Compared with their conventional cohorts in the field, organic farmers get very little help. They receive none of the government subsidies of conventional farmers; very little research is done to enhance yields, tackle weed problems, find new markets or discover new products; very few ag programs are specifically designed to provide information or support in starting an organic farm or helping it remain viable.

The OFRF found in a 1997 study that only 34 of 30,000 USDA projects could be categorized as "strong organic," or highly concerned with organic issues.

Minnesota was ahead of the national curve when it became the second state in the country to define organic requirements in 1986. But other states—not to mention the farm industry—have been slow to the bandwagon. Montana, for example, was one of 10 states to receive organic certification accreditation just this year. On North Dakota's Department of Agriculture Web site, only a single article was devoted to general information on organic farming; South Dakota currently has no state-run organic program to speak of. Only three years ago, there was no such thing as organic livestock.

Basic, comprehensive information on the organic industry is unavailable after 1997, and data on the number of organic farms and farms per state is nonexistent. Catherine Greene, agricultural economist and USDA expert on organic farming, admits that up-to-date information on the industry is hard to come by. "It's been a very hard sector to capture because it's very small, and it hasn't been able to fit into our producer survey system."

Greene also theorizes that the high price of data mining, compounded in small part by a long-standing cultural tradition of conventional farming, is what has kept organic research largely on the backburner. "Data collection is unbelievably expensive. To get any new data is an enormous challenge."

Little help

But the lack of organic data stems at least in part from inertia. Along with the absence of USDA research, ag programs at land-grant universities across the country—a common source of research and support for conventional farming—has all but left the organic field fallow.

An OFRF review of agricultural research at these institutions found that less than two-hundredths of 1 percent of acreage—151 of 883,000 acres—in the land grant system was being used for certified organic research in 1997. About 80 percent of those acres were in Minnesota.

The dearth of government-funded research, aid and other support in the past has forced organic farmers to look to different sources for support and advice. Many attend regional seminars, or band together in formal organizations and informal networks. An OFRF survey of organic farmers found that university extension advisers, state agriculture departments and the USDA were ranked 10th, 11th and 12th (respectively, among 12 resource choices) for their usefulness as information resources.

When they need help or advice, most organic farmers simply ask their neighbors. The OFRF survey found that "other farmers" was the highest-rated information resource. "I've got a neighbor about 20 miles away who's been an organic farmer longer than I have, and he acts as a kind of mentor to me," Schill said.

Robert Quinn co-owns a 700-acre farm near his own farm, where he can experiment with organic techniques. "Every year we experiment somewhere on our farm. It's always in change," he said.

The primrose path: What lies ahead?

Given the size of the industry, some say organic farming is getting proportional attention. North Dakota's 88,000 organic acres, for example, represent three-tenths of 1 percent of the state's 27 million acres of cropland.

Better organization and support for organic farmers also appear to be on the way. For example, the USDA published its final regulation of organic production in December 2000, which mandates that all products labeled or sold as organic must adhere to national standards by Oct. 21 of this year.

The USDA is also making small, but important, strides in researching organic farming techniques and trends, including pilot programs to analyze foreign markets and weed management. Greene is currently at work on an updated report on the organic industry that will contain information from 2000 and 2001, due out sometime this year. Individual states are also joining the effort. Minnesota has an organic cost-share program to defray certification costs for farmers by up to two-thirds, or about $200.

In this year's farm bill, organic farming received about $20 million for several programs along with exemptions from federal marketing orders—a pittance compared to what most other conventional crop farmers got, "but more than we've ever had before," according to a OFRF board member.

Organic farming still has a long way to go in terms of research and promotion before it can command the attention given the conventional farming industry. Even the organic methods already in place are open to scrutiny. As Schill mused, "Yeah, we're organic farmers, but are we really sustainable?" Keep checking the grocery aisle.

| Top 10 U.S. Leaders in Certified Organic Crop Acreage (1997) | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | Acres | Largest Crop (by acreage) |

| 1. Idaho | 107,955 |

Wild Herbs |

| 2. California | 96,851 |

Grapes |

| 3. North Dakota | 88,581 |

Wheat, oats |

| 4. Montana | 59,362 |

Wheat, barley |

| 5. Minnesota | 56,275 |

Soybeans, corn |

| 6. Wisconsin | 41,245 |

Hay/silage, corn |

| 7. Colorado | 35,127 |

Wheat |

| 8. Iowa | 34,276 |

Soybeans |

| 9. Florida | 32,745 |

Wild Herbs |

| 10. Nebraska | 28,104 |

Soybeans |

| Source: Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture | ||