In the Bible, the word "Beulah" is linked to the word "marriage." That association doesn't necessarily hold in the rural farming community of Beulah, N.D. Take 24-year-old Mike Just, a lifelong Beulah resident.

"I'd like to get married and raise a family in Beulah," Just said, "but it's not going to happen if I stay. ... There are only 10 people my age in the area."

The 2000 census put North Dakota in the statistical spotlight when it revealed that almost 90 percent of its counties suffered a population loss. Mercer County, home to Beulah, saw its population drop almost 12 percent during the 1990s. But Just's age group—20- to 29-year-olds—fell by almost 60 percent, or 641 people. He figures he'll stay in North Dakota for another few years and then look for something else. "I don't mind living here," he said. "But I don't think I could live here for a huge amount of time as long as there aren't people my age around."

That story is repeated often in the Ninth District. The perception is that all the young folks are leaving and all the old folks have been left behind. In fact, that's true in many cases. Rural counties in the district saw the number of 20- to 39-year-olds fall 4 percentage points, from 26 percent to 22 percent.

But wait a minute. Metropolitan counties—which saw their overall population increase in the 1990s—also saw the percentage of 20- to 39-year-olds drop almost 6 points to 29 percent. How's that?

This quirk shows that age composition changes in the district in the 1990s are more complex than young people simply leaving. In general, the shift (particularly in rural counties) is the result of three phenomena working in concert: the aging of the baby-boom generation, a flip-flop in birth-death ratios and a trend of out-migration.

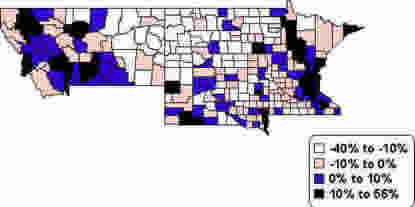

Percent Change in Persons from Ages 0-17, 1990—2000

Source: North Dakota State Data Center

Battle of the bulge

Much of the Ninth District is experiencing an age shift for the same reason: aging baby boomers. Like a pig in a python, age composition in many counties follows the slow movement of the baby boom bulge through the aging process.

For example, the number of people between the ages of 40 and 59 in the district rose by 6 percent, thanks to the comparatively larger number of boomers heading into their 40s and 50s. At the same time, the percentage of people aged 20 to 39 fell by 4 percent—explained in part by the fact that the generation following baby boomers, known as Generation X, is much smaller.

Among district states, Montana is seeing the biggest boomer bulge. From 1990 to 2000, the state experienced a 7 percent increase in the 40 to 59 age group. At the same time, the two age groups below it (20 to 29, and 30 to 39), saw their combined percentage of the population drop by more than 5 percentage points.

Rosebud County, on the Yellowstone River in southeastern Montana, saw large drops in younger age groups, but substantial gains in older age groups. As a result, the county is giving more attention to senior services, said County Commissioner Daniel Watson. Already, Rosebud Health Care Hospital is one of the top 10 employers in the county. The county also recently developed a "retirement-type facility" to house 50 families, Watson said. Although it currently has a high vacancy rate, he expects the residence to fill up over the next decade, as baby boomers hang up their lunch buckets.

Uneven exchange rate

Yet there's more to the story than too many boomers. There's also been a shift in net population increase. More specifically, families have gone from litters to loners as average family size has been sliced substantially over the years. Today, the average number of children is fewer than two.

The downsizing has had a striking effect on the ratio of births and deaths in district counties. Simply put, the population is not replacing itself because many counties are seeing more deaths than births.

According to 2000 data for South Dakota, 44 percent of South Dakota counties "are not replacing themselves through their birthrate," said Nancy Nelson, director of the South Dakota State Data Center. She said it was largely the result of people having fewer babies, but it can accelerate as a county's population ages.

The trend appears to be picking up speed. During the 1990s, 23 of 66 counties (about 35 percent) saw higher death than birth rates. Tripp County could to be one of those sliding down this slippery slope. Even with a town called Winner as its county seat (population about 3,100), the central South Dakota county started losing population. For the decade, Tripp saw about 40 percent more births than deaths, averaging 97 births and 69 deaths. However, in 2000, Tripp County saw one fewer births (79) than deaths (80).

Nineteen-year-old Barry Schramm has been a lifelong resident of Winner, following in the footsteps of both his father and grandfather, and is starting to feel outnumbered. "There are lots of elderly people in our area," he said. Schramm's grandfather, now 84, had 11 brothers and sisters, and "only three or four ever left Winner."

The younger Schramm, on the other hand, has but one sister. As he enters his sophomore year in college this fall, Schramm has no intention of taking over the family furniture business his grandfather started. Instead, this fall he's starting his sophomore year at Dakota Wesleyan University in Mitchell, about 100 miles to the northeast. His younger sister wants to be a pharmacist. Neither plans to stay in Winner.

Home alone

The Schramms are an example of the last, and perhaps most obvious, reason for the population decline: out-migration. Ask anyone who lives in the rural areas of the district about age and population changes in the past decade and they'll give you a familiar answer: Young people are leaving.

"Young people are leaving to go other places," said a commissioner from Mercer County, N.D. An official from the Winner Chamber of Commerce said, "Young people leaving ... that's been the trend for the last 30 years."

Rosebud County, Mont., for example, actually saw a healthy natural increase (births minus deaths) of almost 1,100 in the 1990s. Nonetheless, the county's total population fell by about 1,200—meaning the pace of out-migration was twice the rate of natural increase.

Most are leaving for the big cities. The population of Yellowstone County, Mont., (home to Billings, the state's largest city) grew by almost 16,000 people, and more than half came from in-migration. Minnehaha and Lincoln counties—home to the Sioux Falls, S.D. region—gained about 33,000 people between 1990 and 2000, about 60 percent of whom came from somewhere else.

Not all rural counties are losing the migration game, however. Nine of 21 nonmetropolitan Wisconsin counties located in the district saw a negative natural population tally in the 1990s, but total population increased in every county thanks to net in-migration, many of whom were retirees moving to the lake country in northern Wisconsin.

Indeed, a county's population portrait can get repainted often as it goes through different stages. Even those counties seeing young people leave aren't about to throw in the towel. Their residents are proud of where they live and what they do.

Winner Mayor Rick Curtis said his town has a lot to offer to young and old alike. "We've got wide open spaces, clean air, a good environment and good people." Sooner or later, that might help Winner live up to its name.

Related articles: |