Twenty-five years ago, Dale Thorenson took over the farm he grew up on near Newburg, N.D., from his father. Full of youthful enthusiasm and desire to carry on the family tradition, Thorenson almost never got the chance to run the family farm.

"Dad used to threaten to sell the farm all the time. It used to really bother me. I did not see how he could be so down about things at times," Thorenson said. "Once I had to run the financial part of the farm, I understood why he had felt that way... . The last three or four years, I fully understand where he was coming from."

This past summer, Thorenson's farm stood idle after spring rain flooded land that should have been growing wheat. Now at age 43, with debt rising and income falling, Thorenson has had thoughts of getting out, of stopping the bet-the-farm roller coaster he and countless other farmers have had to endure as part of the modern-day farm economy. But doing so brings the added dilemma of whether he should allow an eager and willing son to take the farm reins from him.

"He is bound and determined to farm," Thorenson said of Kelly, 21, a senior working on an agronomy degree at North Dakota State University. "I cannot in good conscience discourage him. We as a society need people like him to continue in this profession. But sometimes I feel like saying, 'I'm going to sell this damn place.' But I owe it to him, to his late grandfather and great-grandfather to persevere."

Many farmers are staring at a similar decision today in the midst of the worst farm recession in 15 years. As with past recessions, pleas to "save the family farm" are commonplace. In August, North Dakota Sen. Byron Dorgan told a U.S. Senate committee looking at current farm conditions, "If we don't take action soon, we won't have many family farmers left across the bread basket of the country." One day later, Sen. Paul Wellstone of Minnesota told the same committee, "Family farmers are going under, and time is not neutral."

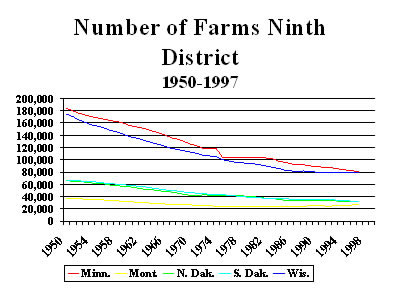

The push to save family farms has been omnipresent since the mid-1930s, when the number of U.S. farms peaked at about 7 million and began a steady consolidation to about 2 million today. Wisconsin saw its farm numbers drop from 200,000 in 1935 to 78,000 today; Minnesota's experience has been almost identical.

But when the whole farm economy goes south, family farm rhetoric is put into action. Farm advocates bemoan the loss of farmsteads and farmland, the increasing size of farms, the dominance of "corporate farms," and the general intrusion of corporate interests into farming.

While there are very real threats facing farmers today, some of the family farm rhetoric overlooks a few basic points. In some cases, legislation to save family farms has even undermined farmers' ability to compete in a new ag economy.

Big farms are bad farms

Still rooted in the nation's nostalgia-driven psyche, the perception of the small family farm—a single farmer providing for his family on a couple hundred acres—and its place in the ag economy has not kept pace with reality. If the idea of "saving the family farm" is to save all small farms, or to make the small farm economically viable and competitive with larger farms, then the family farm has been dead for some time.

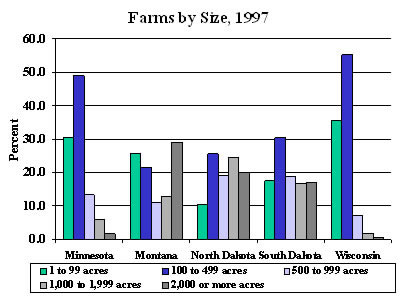

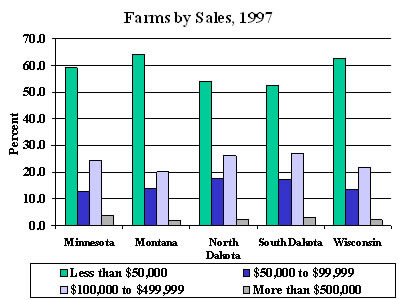

More than 70 percent of all Ninth District farms are considered small, having less than $100,000 in crop or livestock sales. Many of these are not full-time, commercial farms and fall well below that revenue cutoff. More than four of 10 Wisconsin farmers—34,000—had revenue of less than $10,000 in 1997.

Small farms have typically been under the greatest economic pressure. Five of six Minnesota farmers who went out of business from 1993 to 1998 were small farmers. In North Dakota, the number of small farms dropped by almost 7,000 from 1989 to 1997, while large farms grew by 4,200.

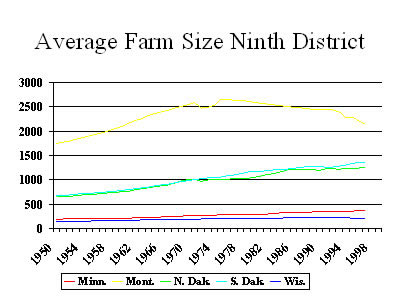

Despite the persistent loss of farmers and a small erosion of total land in farms, the number of harvested acres has held relatively stable, which means surviving farms are getting bigger. In Minnesota, the average farm has grown from 180 acres in 1950 to 290 acres in 1975, and is now at 360 acres.

But not all farms are created equal. The average size farm in Montana, where cattle operations demand significant grazing lands, is over 2,000 acres (a decline of some 500 acres in the last 25 years due to the popularity of smaller hobby farms). Average farm size in South Dakota is 1,400 acres, while the traditionally smaller size of dairy operations has kept Wisconsin's average farm to just 210 acres.

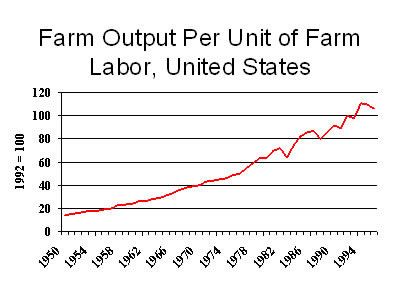

Mechanization and other technology advancements have dramatically improved farm productivity, allowing the individual farmer the opportunity to grow more crops or raise more livestock than in years past. It is to the full-time farmer's advantage to expand operations as (nonlabor) production capacity increases. But some believe mechanization has run its course in expanding production given today's farm structure. "The treadmill of getting bigger to survive is self-defeating," Thorenson said. "One individual can only do so much."

Farm advocates have used ballooning farm size as evidence of food consolidation. They point out that just 4 percent of farms and ranches produce 50 percent of all agricultural output. But U.S food and fiber has never been evenly produced by all farmers, and has always been in the hands of a minority number of farmers. As early as 1900, just 17 percent of farmers produced half of the nation's food basket, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Many people erroneously think the family farm ceases to exist as farms get bigger. By that definition, Dale Thorenson could be considered Farming Enemy #1. He farms 3,400 acres and decided to incorporate his operation three years ago because it allows him to see "exactly what the farm is doing." He pays himself a salary, and pays rent on the land he already owns.

The switch made him "one of those" corporate farms, despite the fact that he is a third-generation farmer, and his son hopes to continue the tradition. "It does make business sense" to incorporate farms because of the tax advantages, Thorenson said, but only if a farm can turn a profit. With marginal income, "the move to the family farm corporation may have been a case of zigging when one should have been zagging," Thorenson said. "I am not sure if I would do it over again if the clock could be turned back."

Still a lot of family farms

Without doubt, the nature and operation of the family farm today has changed, as it has for most of this century. But in fact, family-controlled farms still make up 99 percent of all farms. Close to nine of 10 farms in the Ninth Federal Reserve District (except in Montana, with eight of 10) are operated by an individual or family as a sole proprietorship (the "traditional" family farm). The remaining farms are mostly either partnerships or corporate farms, which despite being vilified by many, are predominantly operated and controlled by families.

Corporate farms made up just over 4 percent of all farms nationwide in 1997—double the percentage two decades ago—and are grabbing a bigger chunk of the production and sales pie. But contrary to the glass-building image of corporations, 90 percent of the 84,000 corporate farms in the United States are family owned, whose shareholders (usually capped at 10 or fewer) are usually required to have close kinship to the farm operator (e.g., brother, father, grandmother). What's more, since 1978, sales from nonfamily corporate farms have dropped while sales by family-owned corporate farms have surged by 50 percent.

North Dakota, for example, has about 30,000 working farms, meaning they have crop or livestock sales of more than $1,000. Of this total, 87 percent (26,600) are sole proprietorships, with another 10 percent in family-based partnerships. The state has just 550 corporate farms (less than 2 percent), and only 29—one-tenth of 1 percent—are nonfamily corporations, whose average size of 930 acres is smaller than the state average of 1,200 acres for sole proprietorship farms.

The continued control of farming by families comes through very deliberate design. State laws in the Dakotas, Minnesota and Wisconsin, for example, expressly forbid corporations or limited liability companies from having much of any stake in a farming operation.

Were farm ownership opened up to all comers, the average farmer wouldn't have the resources to compete with cash-flush corporations, farm proponents argue. Family farm laws—many of which have been on the books for decades—keep multi-national and other corporations "from gaining control of those [farm] resources," according to Paul Germolus, an assistant attorney general for North Dakota. The few existing nonfamily corporate farms can be attributed to various loopholes in state regulations, he said.

Such laws do not always hit their mark, however. While controlling the number of nonfamily farms, laws have been powerless against increasing farm size. The average family farm has been getting bigger as a matter of survival, yet is often the smallest of the farm litter by a considerable amount. Many corporate farms are "family" in ownership but not in operation, farming many thousands of acres with the help of additional hired hands, making relative dwarfs out of even farm partnerships and nonfamily corporate farms.

Family farm laws also have unintended consequences. For one, laws preventing nonfamily involvement in farming can be an obstacle to farmers looking to organize cooperatives or other activities that might open up new markets and leverage greater selling power for farmers, Germolus said. This is exactly what has happened in South Dakota, where well-intentioned lawmakers passed a constitutional amendment, known as "Amendment E," about a year ago that prohibits most limited liability companies and partnerships from owning any interest in farmland, ranchland or livestock within state borders.

"Proponents are trying to stop some of the concentration going on, particularly in livestock production," said Michael Held, administrative director of the South Dakota Farm Bureau. While the bureau shares concerns over the consolidation in agribusiness, Held said, it nonetheless has filed suit against Amendment E.

"Things are changing and farmers are interested in forming alliances," particularly with other local farmers, Held said. Some farmers have found that they have "a little more market power by three, four, five farmers doing it together."

Amendment E outlaws such activity unless all members of an alliance are related. The new law actually made criminals of some existing South Dakota ranchers whose operations "are now in violation of the state's constitution," Held said.

Acknowledging legislators' good intentions, Held said that instead of using a "rifle approach" to target their objective, "they used a shotgun blast."

Contracts and farm (in)dependence

Some of the hand wringing over family farms is rooted in the traditional notion of the family farm as wholly independent, which many believe is being eroded by vertical integration of food processing.

Consumer food companies are using vertical integration to control more facets of the food production process, from seed sales to feed mills to grain elevators to processing plants and distribution networks. The final step in fully integrating this seed-to-shelf structure is to control the animal or crop commodity itself. Despite anti-corporate farming laws in many states, commodity control can still be accomplished through forward contracts, where a buy-sell agreement is made in advance between a farmer and buyer for a particular volume and quality of commodity.

Critics of contracting believe it undermines the independence and decision-making of individual farmers. Only open market cash sales provide true independence, they contend-despite the fact that many areas of agriculture have been contracting for decades.

The federal government does not have up-to-date data on contracting, but as of 1993, roughly one-third of the total value of U.S. ag production was produced under contract. Contracts are believed to be even more popular today because they provide farmers with price and income stability unavailable through the open market.

Dairy, vegetables, fruit, nursery, cotton, and cattle and poultry have at least one-third of their total product value generated under contract. Corn, wheat and soybeans generate significantly less of their total value from contracts, according to various sources, despite evidence that some contracts paid corn and wheat farmers significantly more than the open market last year.

Many remain wary of forward contracts and what it means for the average farm. Production contracts, for example, remove the farmer from virtually all risk, but all decision-making as well. The contractor supplies or pays for most inputs, owns the commodity being produced and essentially rents a farmer's growing skills. Held said opponents "think of contract production as slave labor."

But at least some farmers see contracting as a means for remaining viable given today's low commodity prices. "People see [contracting] as a risk management tool," Held said, adding most farmers using contracts were in their mid-30s to age 50 and operating large farms. "It's an option for some [farmers], and not for others."

The best farming option for Thorenson right now is in Washington. A regular columnist on farm issues and vice chairman of the North Dakota Democratic-NPL Party, Thorenson recently accepted a farm policy position with Sen. Dorgan's office. With all the circumstances, Thorenson said, "It seemed like the right thing to do." Thorenson and his wife, Cindy, are moving to Washington-ironically, something they'd be unable to do at this time of harvest were it not for the hard luck that hit last spring-and Kelly will take over the farm.

When Dale first mentioned the job in Washington, Kelly said he wanted to run the farm with his father. Dale said that was not feasible. "There is enough work for three of us, but hardly enough pay for one."

Dale's new job will give his son the opportunity to fulfill a dream. "He's excited," Thorenson said of Kelly, "but it's kind of a daunting thing."

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.