Note1

Thank you very much for that generous introduction. It is a special pleasure to meet with this group so soon after the announcement that two of your fellow alums have been awarded the 2011 Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. I am referring, of course, to Thomas Sargent and Christopher Sims, and I would like to begin my remarks by congratulating Tom and Chris on this well-deserved honor. In the 1970s, in independent research, they developed systematic approaches to distinguishing between cause and effect in macroeconomic data. Now, almost 40 years later, their thinking informs the making of macroeconomic policy around the world.

I am especially pleased to acknowledge Chris and Tom’s achievement because of their connection to the state of Minnesota. After earning their Ph.D.s in economics at Harvard, where Chris also received his undergrad degree in mathematics, Tom and Chris went on to do much of their Prize-winning work right here in Minneapolis, as professors at the University of Minnesota and consultants at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. I’m sure that many of you in the room today followed that same career path, from an education at one of America’s oldest colleges to accomplishing great things here in the North Star State.

In my remarks today, I’d like to touch on several topics. I’ll begin with a quick description of the structure of the Federal Reserve System and the deliberative process of the Federal Open Market Committee—the Committee that makes monetary policy for the nation. Then I’ll describe the FOMC’s objectives and discuss how the FOMC makes decisions so as to achieve those objectives. I’ll close with a discussion of my dissents on recent FOMC decisions and some perspectives on monetary policy going forward. After that, I’ll be pleased to answer any questions you may have. And before I begin, I should remind you that my comments here today reflect my views alone, and not necessarily those of others in the Federal Reserve System, including my FOMC colleagues.

Some FOMC basics

The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis is one of 12 regional Reserve banks that, along with the Board of Governors in Washington, D.C., make up the Federal Reserve System. Our bank represents the ninth of the 12 Federal Reserve districts, and by area, we’re the second largest. Our district includes Montana, the Dakotas, Minnesota, northwestern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

Eight times per year, the FOMC meets to set the path of monetary policy over the next six to seven weeks. All 12 presidents of the various regional Federal Reserve banks—including me—and the seven governors of the Federal Reserve Board, including Chairman Bernanke, contribute to these deliberations. (Currently, there are only five governors—two positions are unfilled.) However, the Committee itself consists only of the governors, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and a group of four other presidents that rotates annually. Right now, that last group consists of the presidents from the Minneapolis, Philadelphia, Dallas and Chicago Federal Reserve Banks.

I’ve said that the FOMC meets (at least) eight times per year. But how do these meetings work? At a typical meeting, there are two so-called go-rounds, in which every president and every governor has the opportunity to speak without interruption. The first of these is referred to as the economics go-round. It is kicked off by a presentation on current economic conditions by Federal Reserve staff economists. Then, the presidents and governors describe their individual views on current economic conditions and their respective outlooks for future economic conditions. The presidents typically start by providing information about their district’s local economic performance. We get that information from our research staffs, but also from our interactions with business and community leaders in industries and towns from across our districts.

The chairman speaks at the end of the first go-round. He briefly but thoroughly summarizes the preceding 16 perspectives. I can assure you that this is no easy task—and the chairman’s balanced and thoughtful treatment of our remarks is one of the many reasons that he commands such respect among his colleagues. He then provides his own views on the economy.

The Committee next turns to the second go-round, which focuses on policy. Again, the staff begins, with a presentation of policy options. After that, each of the 17 meeting participants has a chance to speak on what each views as the appropriate policy choice. This set of remarks is followed by a summary by the chairman, in which he lays out what he sees as the Committee’s consensus view for future policy. The voting members of the FOMC then cast their votes on this policy statement and thereby set monetary policy for the next six to seven weeks.

I hope that this description of an FOMC meeting conveys two things. First, the meeting participants view monetary policy as a largely technocratic exercise that is fundamentally apolitical. As I mentioned earlier, our policy discussions are largely based on information-gathering and model analyses by meeting participants and their staffs. I would say that the tone of the discussion is pretty much in accord with its rather technical substance. There is disagreement, of course. How could there not be in such challenging and unusual economic times? But, as a relative newcomer, I’ve been impressed with how the dialogue within the meeting room is always fundamentally grounded in a deep respect for the job at hand and for each other.

Second, my description of an FOMC meeting highlights how the structure of the FOMC mirrors the federalist structure of our government. Representatives from different regions of the country—the various presidents—have input into FOMC deliberations. And, as I’ve described, their input relies critically on information received from district residents. In this way, the Federal Reserve System is deliberately designed to give the residents of Main Street a voice in national monetary policy.

FOMC objectives

I’ve said that FOMC participants seek to adopt what they view as the appropriate policy choice. That provides a natural segue into my next topic: the policy objectives of the FOMC. The FOMC has a dual mandate, established by Congress: to set monetary policy so as to promote price stability and maximum employment. In my view, the heart of implementing the price stability mandate is to formulate and communicate an objective for inflation. The central bank then fulfills its price stability mandate by making choices over time so as to keep inflation close to that objective.

Of course, the central bank’s job is complicated by economic shocks that may lower or raise inflationary pressures. The central bank provides additional monetary accommodation—like lower interest rates—in response to the shocks that push down on medium-term inflation. It reduces accommodation in response to the shocks that push up on inflation. By doing so, it works to ensure that inflation stays close to its objective.

It is not enough to have an objective—the Federal Reserve must also communicate that objective clearly and credibly. That communication serves to anchor the public’s medium- and long-term inflationary expectations. Put another way, without clear communication of objectives, the public can only guess at the intentions of the FOMC, and inflationary expectations and inflation itself will inevitably end up fluctuating—and perhaps by a lot. It is possible to undo these shifts in expectations, but doing so entails significant economic cost. The nation saw this all too clearly in the early 1980s, when tighter monetary policy necessary to rein in high inflation resulted in painful employment losses.

The Federal Reserve communicates its objective for inflation in a number of ways. For example, at quarterly intervals, FOMC meeting participants publicly reveal their forecasts for inflation in the longer run (maybe five or six years), assuming that monetary policy is optimal. Those forecasts usually range between 1.5 percent and 2 percent per year. They are often collectively referred to by saying that the Federal Reserve views inflation as being “mandate-consistent” if it is running at “2 percent or a bit under.”

Congress has also mandated that the FOMC set monetary policy so as to promote maximum employment. Some see an intrinsic conflict between the FOMC’s price stability mandate and maximum employment mandate. But there is actually a deep sense in which the price stability and maximum employment mandates are intertwined. Imagine that inflation runs at 3 or 4 percent per year for three or four years. The public will then start to doubt the credibility of the Fed’s stated commitment to a 2-percent-or-a-bit-under objective. The public’s medium-term inflationary expectations will consequently begin to rise. As we saw in the latter part of the 1970s, these changes in expectations can serve to reinforce and augment the upward drift in inflation. At that point, the Federal Reserve will have to tighten policy considerably if it wishes to regain control of inflation. But we learned in the early 1980s that the resultant tightening—while necessary—generates large losses in employment. In other words, failing to meet its price stability mandate can also lead the FOMC, over the medium and long term, to substantial failure on its employment mandate.2

An important and ongoing communications challenge for the FOMC is that it is much harder to quantify the maximum employment mandate than the price stability mandate. Changes in minimum wage policy, demography, taxes and regulations, technological productivity, job market efficiency, unemployment insurance benefits, entrepreneurial credit access and social norms all influence what we might consider “maximum employment.” Trying to offset these changes in the economy with monetary policy can lead to a dangerous drift in inflationary expectations and ultimately in inflation itself.

Over the past year, the FOMC has communicated through its statements that it perceives the current unemployment rate to be elevated relative to levels that it views as consistent with its dual mandate. In this situation, there is a trade-off involved in the making of monetary policy. On the one hand, adding monetary accommodation reduces unemployment. On the other hand, adding accommodation increases the risk of generating inflation markedly higher than the Committee’s objective of 2 percent for a significant period of time. In choosing whether to add monetary stimulus or not, the Committee must resolve this trade-off between the fall in unemployment and the increase in the risk of inflation.

I’ve described the relevant trade-off in the traditional way as being one between employment gains and inflation risks. This description emphasizes a tension between the two mandates of the Federal Reserve. But, as I explained earlier, if the public observes inflation running at more than 2 percent for multiple years, their inflation expectations may drift upward. This increase in expectations can give rise to a need for monetary tightening that may generate large employment losses. In other words, when thinking about adding monetary accommodation, the Federal Reserve confronts a basic trade-off that can be framed without reference to its price stability mandate: a trade-off between short-term employment gains and the risk of larger longer-term employment losses.

Making monetary policy: Responding to a mandate dashboard

The FOMC’s dual mandate, as I’ve said, is to keep inflation at 2 percent or a bit under and to promote maximum employment—that is, to keep unemployment low. But how does the FOMC make its choices at each meeting so as to achieve these goals? I believe that it is useful to think of a driver who is trying to maintain a car speed. To do so, he’ll vary pressure on the accelerator in response to changes in road conditions, current and expected: hills, valleys, rough pavement, headwinds. In the same way, the FOMC varies its chosen level of monetary accommodation in response to changes in current and expected economic conditions.

This kind of systematic response to changing economic conditions is an essential part of good monetary policy for at least two reasons. First, there is a great deal of empirical evidence and theoretical support for the idea that following a policy rule, as economists call it, is what enables the Committee to achieve its dual mandate goals. Second, and perhaps more importantly, actions speak louder than words. The Committee can claim that it intends to make monetary policy so as to fulfill its dual mandate. But the public can and does watch its actions carefully in this regard. If the Committee fails to reduce its immense amount of accommodation in a timely fashion, the public may well begin to doubt the Committee’s claims about its goals.

Right now, the Federal Reserve has multiple forms of accommodative monetary policy in place. For example, the FOMC is targeting a fed funds rate of between 0 and 25 basis points—that is, between 0 percent and 0.25 percent. This kind of accommodation—keeping short-term interest rates extremely low—is an entirely conventional response to unduly low levels of inflation and unduly high levels of unemployment. By keeping market interest rates low, the policy encourages companies to invest in hiring and business expansion, and it encourages households to spend more. The Committee has announced that it anticipates that conditions will be such that the fed funds rate will stay between 0 and 25 basis points for at least 20 more months.

The second kind of accommodation is less conventional. The Fed has bought over $2 trillion of longer-term government securities and has announced its intention to buy still more. The goal of this form of accommodation is to raise the prices of longer-term securities and lower longer-term yields. In so doing, more long-term investments—like building factories or hiring workers—become more attractive to businesses.

This combined package of accommodation is really unprecedented. As I’ve described at some length in earlier speeches, I believe that it has been critical in keeping inflation from falling lower and unemployment from rising higher.3 But, as economic conditions improve, the FOMC will need to reduce the amount of accommodation that it is providing. What conditions are relevant? Again, I think that it’s useful to think of a car driver who is trying to maintain his speed. To know how much (or how little) acceleration to provide, the driver would certainly like to know his current speed. As well, he would like to know how future road conditions—like hills—are likely to affect his future speed.

The FOMC’s problem is quite similar. Just like the driver needs to know his current speed, the FOMC needs an accurate measure of current inflation and unemployment. Just as the driver needs an estimate of his future speed, based on anticipated road conditions, the FOMC should have an assessment of the future levels of inflation and unemployment.

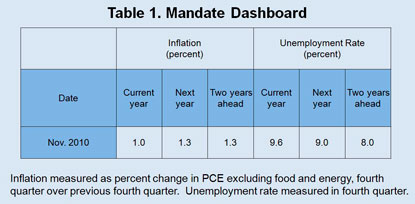

I find it helpful to summarize the relevant information in what I term a mandate dashboard. For reasons that will become clear later in my remarks, I think that it’s useful to start by looking at the dashboard from early November 2010—that is, from about a year ago. I’ll explain the dashboard starting with the inflation side. The first cell from the left is current inflation. The second cell is what inflation is projected to be in one year’s time. Finally, the third cell contains a forecast for inflation in two years’ time. The unemployment side is similar. The first cell from the left represents current unemployment. The second cell represents a forecast for unemployment in one year’s time, and the third cell represents a forecast for unemployment in two years’ time.

Of course, I have to be a little more precise in what I mean by inflation and unemployment. By “inflation,” I mean the change in the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index over the preceding four quarters, excluding changes in the prices of food and energy. Hence, my measure of inflation in the dashboard is what is commonly called “core inflation.” I’m using core inflation because I view it as a good measure of overall inflationary pressures over the next two to three years.

By “unemployment,” I mean the unemployment rate averaged over the three months in the current quarter. The forecasts for future inflation and unemployment are the midpoints of the central tendencies of the projections of FOMC participants that they released in November.

Just as a driver should adjust acceleration according to information provided by his dashboard, the FOMC should vary the level of monetary accommodation in response to changes in the mandate dashboard. The exact quantitative response will depend on the precise movements of the six variables and on how the FOMC is resolving the trade-off that I mentioned earlier between inflation risks and unemployment reductions. But the qualitative direction of the response is typically easier to determine. For example, the November 2010 dashboard shows that the FOMC expected the unemployment rate to fall over time—slowly—and the inflation rate to rise—slightly. As that happens, the FOMC should respond by slowly lowering its immense level of monetary accommodation.

Recent inconsistency in monetary policy actions

I picked November 2010 as a good base date because at that point in time, the FOMC added considerably to the level of monetary policy accommodation. The Committee undertook the purchase of $600 billion of long-term Treasuries over the following eight months, in what was called QE2. I supported this action within the meeting and then later publicly. The Committee took no further significant policy action until the last two meetings in August and September 2011, at which the FOMC added considerably more accommodation.

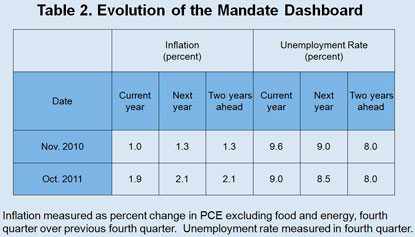

I dissented from the FOMC decisions at these last two meetings. My thinking behind those dissents is grounded in the evolution of the mandate dashboard over the past year. The entries for November 2010 are exactly what I’ve already shown you, and they’re based on the FOMC’s economic projections. The FOMC’s most recent 2011 projections date back to June, and so the entries for October 2011 are based on my own forecasts. The fourth quarter is not yet complete, but it looks like fourth-quarter-over-fourth-quarter PCE core inflation in 2011 will be around 1.9 percent. I expect it to rise over the next couple of years to slightly above 2 percent. At the same time, unemployment is 9.1 percent. I expect it to fall slowly to around 8 percent by the end of 2013. I should say that private sector forecasts for inflation over the next two years are probably closer to 1.6 percent rather than 2.1 percent. However, my forecasts for unemployment are roughly similar to those of private sector forecasters.

Notice that the second cell for the November 2010 row is the forecast for inflation over the course of 2011, and the second cell for the October 2011 row is the forecast for inflation over the course of 2012. We generally think that monetary policy operates with a one- or two-year lag. Accordingly, the dashboard keeps track of what we expect the economy to be like in a year or two.

Regardless of whether my forecasts or the private sector forecasts are used, inflation—and the outlook for inflation—has risen markedly since last November. Unemployment—and the outlook for unemployment—has fallen. These changes in the mandate dashboard suggest that the Committee should have lowered the level of monetary accommodation over the course of the year. Instead, the Committee chose to raise the level of monetary accommodation. The Committee’s actions in the last two meetings are thus inconsistent with the evolution of the economy in 2011. Given this inconsistency between the Committee’s actions and the evolution of the economy, I decided to dissent in August and September.

I want to be clear about one important point. Like many private sector forecasters, the FOMC has overestimated the strength of the recovery over the past two years. Some have suggested that the unexpected slowness of the recovery is a justification for the FOMC’s increasing the level of monetary accommodation over the past couple of months. But I disagree with this argument. I’ve just described why the FOMC should respond to improvements in economic conditions and outlook with a reduction in the level of monetary accommodation. Logically, if the economy recovers much more slowly than expected, then the FOMC should respond by reducing the level of monetary accommodation much more slowly than expected. The FOMC should only increase accommodation if the economy’s performance and outlook, relative to the dual mandate, actually worsens over time.

Conclusions

Let me wrap up with some final thoughts about 2011 and a look ahead to 2012. Earlier in my speech, I set forth what I see as a key trade-off involved in the making of monetary policy. There is a benefit to adding monetary accommodation: It reduces unemployment. There is a cost to adding monetary accommodation: It increases the risk of inflation running above the Committee’s objective of 2 percent for multiple years. The FOMC’s actions in 2011 suggest that the Committee is resolving this key benefit-cost trade-off differently in 2011 from however it viewed the trade-off in 2010. In particular, it appears that the Committee is now more tolerant of the risk of higher-than-2-percent inflation than it was in 2010.

Moreover, as I explained earlier, one can reframe this trade-off in a way that is entirely separate from the price stability mandate. Higher-than-2-percent inflation over multiple years might lead to an upward drift in inflationary expectations. The Fed found in the 1970s that this upward drift could only be retarded by large medium- and long-term employment losses. Thus, I view the basic unemployment-inflation trade-off in the making of monetary policy as really being about short-term employment gains and the risk of larger longer-term employment losses. The FOMC’s actions in 2011 suggest that it is resolving this trade-off differently from however it viewed the trade-off in 2010. In particular, it appears that the Committee has reduced the weight that it is putting on the long term and increased the weight that it is putting on the short term.

Now, I should be clear: I don’t view the Committee’s current resolution of this trade-off as being intrinsically problematic. Nor did I view the Committee’s resolution of this trade-off in 2010 as being intrinsically problematic. What I do see as problematic is that the Committee’s resolution of this trade-off appears to be changing over time. In particular, the Committee’s actions in 2011 suggest that it is more willing to tolerate inflation risks—and the concomitant medium-term and long-term employment losses—than it was in 2010. If this drift in inflation risk tolerance were to persist, or were expected to persist, it could give rise to a damaging increase in inflationary expectations. It is exactly in this sense that I have said in earlier speeches that the Committee’s actions in 2011 served to weaken the Committee’s credibility.

But enough about the past—what about the future? I believe that the FOMC’s decision-making in 2011 has introduced a lack of clarity about its monetary policy mission. I believe that this lack of clarity can and should be addressed in two steps. First, the FOMC should explain how it plans to resolve the trade-off between inflation and unemployment in making its future decisions. Second, on an ongoing basis, the Committee should provide explicit communication about how its chosen actions are indeed consistent with its pre-announced resolution of the inflation-unemployment trade-off. Here, I believe that the use of metrics like the mandate dashboard provides a useful form of discipline—both on our own actions and on the public’s understanding of those actions.

In a speech he gave last May, Chairman Bernanke stated, “Transparency regarding monetary policy … not only helps make central banks more accountable, it also increases the effectiveness of policy.”4 I agree completely with this sentiment. And I see my two recommended future steps—clearer communication about trade-offs and the explicit use of metrics like the mandate dashboard—as promoting exactly the kind of transparency that Chairman Bernanke was describing.

Thank you for listening. I look forward to taking your questions.

Endnotes

1 I thank Doug Clement, David Fettig, Terry Fitzgerald and Kei-Mu Yi for their helpful comments.

2 The discussion in this paragraph is largely consistent with the following quote from Chairman Bernanke’s response to a reporter’s question in April about the Fed’s ability to lower the rate of unemployment more rapidly: “even purely from an employment perspective—that if inflation were to become unmoored, inflation expectations were to rise significantly, that the cost of that in terms of employment loss in the future, as we had to respond to that, would be quite significant.” (See transcript of Chairman Bernanke’s April 27, 2011, press conference, p. 14.)

3 See, most recently, my Oct. 13, 2011, speech, “Making Monetary Policy” and my Sept. 6, 2011, speech, “Communication, Credibility and Implementation: Some Thoughts on Current, Past and Future Monetary Policy.”

4 See Chairman Bernanke’s May 25, 2010, speech, “Central Bank Independence, Transparency, and Accountability.”