Policymakers across the United States are searching for ways to ease the financial burden of housing expenses for local residents. In many places, housing costs have risen substantially faster than typical income growth in recent decades (Acolin and Wachter 2017; Schuetz 2019a). A typical market response to rising prices is expanded supply, but new housing construction has often been slow to materialize and expensive when finished.

This raises questions about the ability of the market to generate housing that meets the needs of a broad range of local residents. To respond to these questions, the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and the Future of the Middle Class Initiative at the Brookings Institution partnered to bring together researchers and policy practitioners for a series of conversations about what we know and how to proceed. The result was a two-day conference: “Expanding and Diversifying Housing: Approaches and Impacts on Opportunity,” summarized in this brief.1

Cities and states will have to address specific local needs, but a foundation of broadly applicable research that informs key questions, like that summarized here, will be key to finding effective solutions.

1. Can new market-rate housing lower housing prices metrowide?

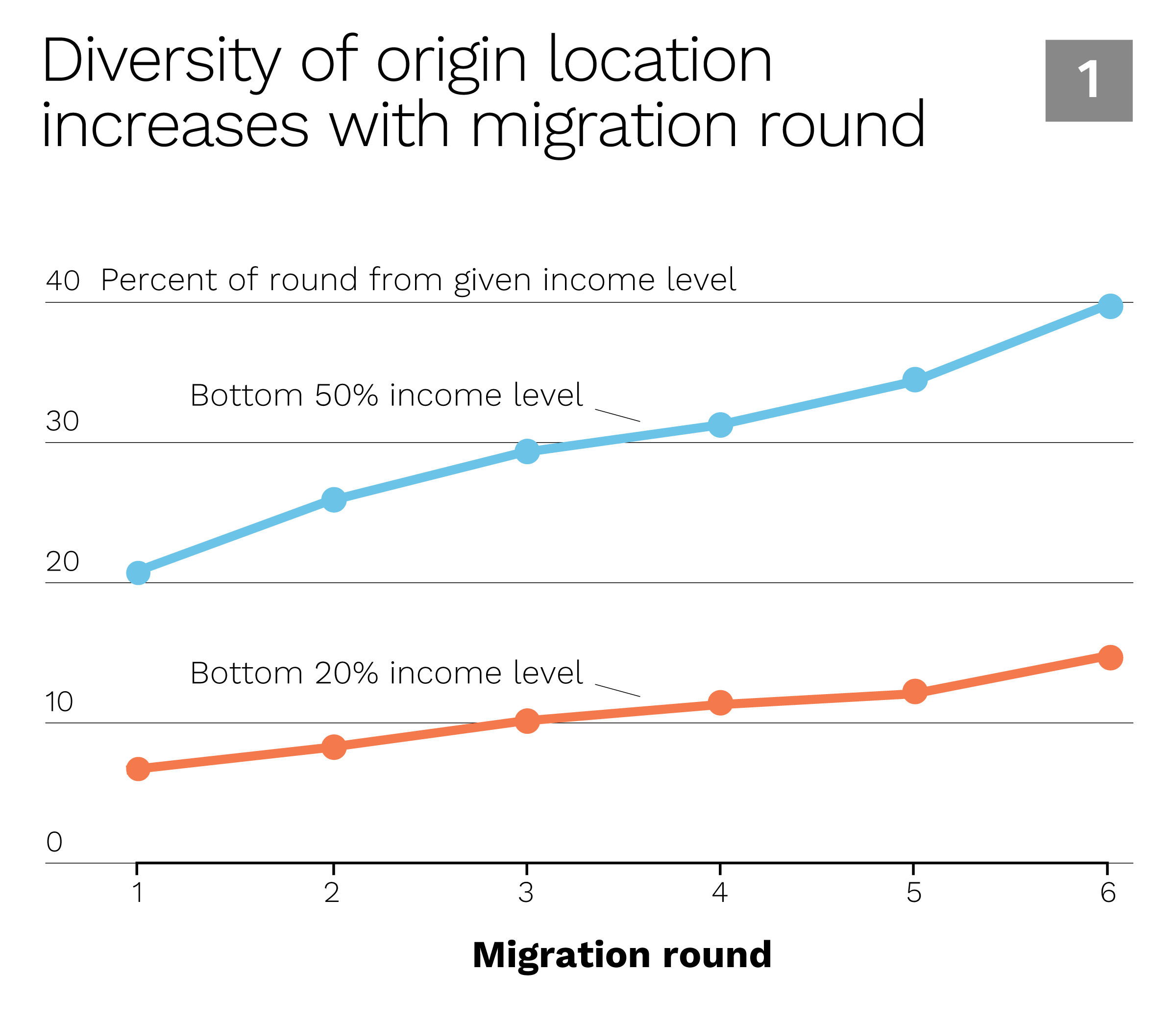

Source: Mast (2019), used by permission of the author

Note: Includes 12 of the largest metropolitan areas in the United States. Metropolitan area is defined according to the most recent core-based statistical area (CBSA) definition. Only migrants from the same metropolitan area as the new building are included in each round. Round 1 is the origin units of the individuals currently occupying the new unit; round 2, the origins of the individuals occupying round 1’s origin buildings, and so on. Tract characteristics are taken from the 2013-17 American Community Survey, and all quantiles are computed within CBSAs. Income is median household income within a tract. Each subsequent round is constructed by observing the set of individuals currently living in the previous round’s origin buildings, not their specific units, and the sequence is reweighted accordingly. The sequences begin with 52,000 individuals living in 686 new market-rate buildings.

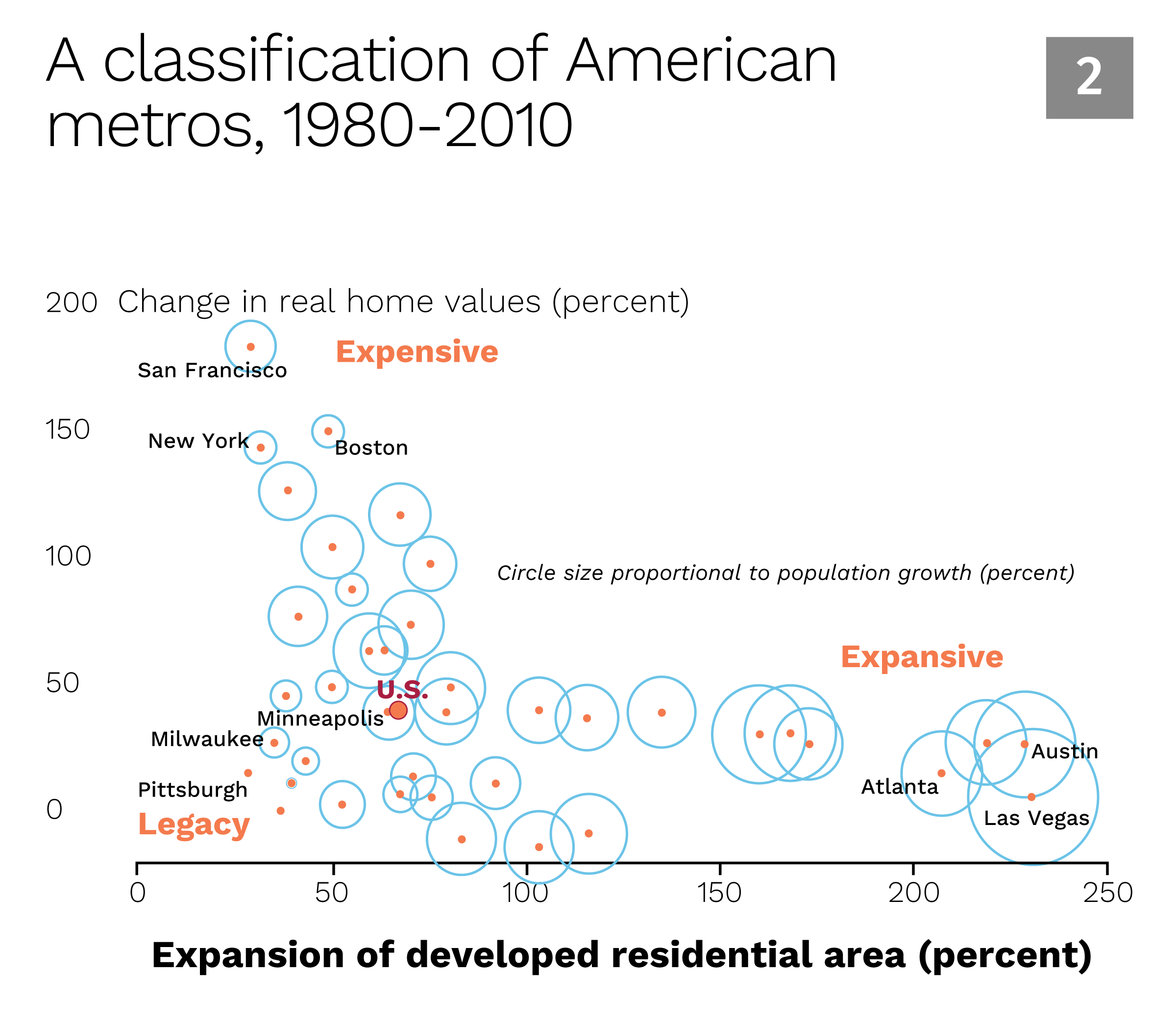

Source: Romem (2016), used by permission of the author

Note: Observations include the 40 most populated U.S. conurbations. The chart considers residential areas as developed when they exceed a density of 200 existing homes per square mile. Developed areas correspond to combined statistical areas (CSAs), or to CBSAs that are not part of a CSA. Housing prices are always at the CBSA level. The change in housing prices is the percent change in average inflation-adjusted quarterly housing prices during the decades spanning 2005-14 and 1975-84.

Supply and price

It can sometimes be difficult to see how building new housing could lower housing costs for a broad set of local residents. Whether new housing is large, single-family homes on suburban lots or luxury apartment towers in a city center, it is often priced well above median home prices for its area (JCHS 2019). Yet connections throughout a local housing market mean that changes in supply for one set of residents can lead to changes in prices for another set.

Research by Evan Mast (Upjohn Institute) demonstrates how these links lead to new housing options for a broad spectrum of local residents even when only new market-rate apartment units are built. Figure 1 shows that, on average, the opening of a new market-rate building generates six or more waves of housing relocations by local residents. Few residents of the new building come from the lower-income neighborhoods (20 percent in round 1), but relocations into newly available units reach more residents of lower-income neighborhoods in each round.

Expensive, high-density housing development in central cities is a visible example of expanding supply, but metropolitan areas have added housing in a variety of ways. Issi Romem (MetroSight) assembled information on whether metros had expanded by converting land to denser residential neighborhoods alongside data on local housing prices. Figure 2 shows three types of metro experiences over the past two decades: those that expanded their residential area substantially with modest price increases (Expansive Metros), those that had substantial price increases and little residential expansion (Expensive Metros), and those that had little of either (Legacy Metros). The relationships suggest a diversity of urban experiences since 1980. Some metros saw steep increases in demand from residents—more people wanted to live and work there. Those that responded by expanding supply by this measure saw more modest price increases; those that did not saw steeply rising prices. Other metros faced flat demand or even decreased demand from residents and likely face a different set of challenges.

Addressing skeptics

The evidence in Figures 1 and 2 shows that expanding housing in a metro area moderates price increases and creates new housing options for residents. This is true regardless of whether cities grow “up” or “out.” Yet residents and policymakers sometimes question whether new housing development will improve affordability in their city.

Ingrid Gould Ellen (New York University) outlined the evolution of this concern, which she terms “supply skepticism.” Traditionally, housing development discussions were framed as a trade-off between more housing with lower prices versus less housing with higher prices and less congestion or other community attributes. More recently, groups concerned with affordability have questioned whether market-rate development will lower prices. In other words, the skeptics question whether there is a trade-off at all. Gould Ellen marshaled a range of evidence, in addition to that in Figures 1 and 2, that suggests that building more housing lowers costs and improves access for many city residents (Gyourko and Molloy 2015; Ihlanfeldt 2007; Jackson 2016; Saks 2008; Zabel and Dalton 2011). However, Gould Ellen is clear that there are limits to how many residents the market will reach. “We are never going to get [all the way] there through supply when … incomes aren’t high enough to cover operating costs. … So … supply is one tool that we have in our toolbox,” she said.

Measuring density, regulation, and diverse impacts

An obstacle to construction of additional market-rate units can be local regulations. Measuring the stringency of regulation within and across metropolitan areas is extremely challenging. Researchers have used a variety of methods to measure regulations, from cataloging specific zoning components to asking local planners their subjective impressions of restrictiveness (Gyourko et al. 2008; Lewis and Marantz 2019; Schuetz 2019b). Most empirical studies find that tightly regulated jurisdictions build less housing and have higher housing costs than loosely regulated jurisdictions, although the estimated size of impacts varies widely across studies (Gyourko and Molloy 2015). Robert Ellickson (Yale) reported on efforts to measure local regulation through careful and consistent monitoring of density permitted on each tract in a metro area. Specifically, he discussed two types of indicators: whether local governments allow multifamily housing and the minimum lot size required for single-family houses. He found wide variation in these measures between Austin, Texas; Silicon Valley, Calif.; and New Haven, Conn.

Tsur Somerville (University of British Columbia) remarked that metro area housing policy is “making the statue out of a block … it’s a lot of little cuts.” This comment reflects the many trade-offs policymakers have to consider, given that the benefits and costs of new housing supply will vary greatly from resident to resident. Somerville’s work analyzing the impact of density increases in Vancouver, B.C., via the city’s “laneway homes” policy illustrates these trade-offs (Davidoff et al. 2019). The policy allowed small secondary dwelling units to be built on single-family home lots beginning in 2009. Analysis following the change showed that the impact of additional density on a neighbor’s plot on home prices varied by how expensive the home was initially. Adding a laneway home on a neighboring lot had no impact on home prices for most homeowners. But for the most expensive 25 percent of homes, nearby laneway homes were associated with decreased housing prices.

2. Can improving access to housing in growing areas improve outcomes for residents?

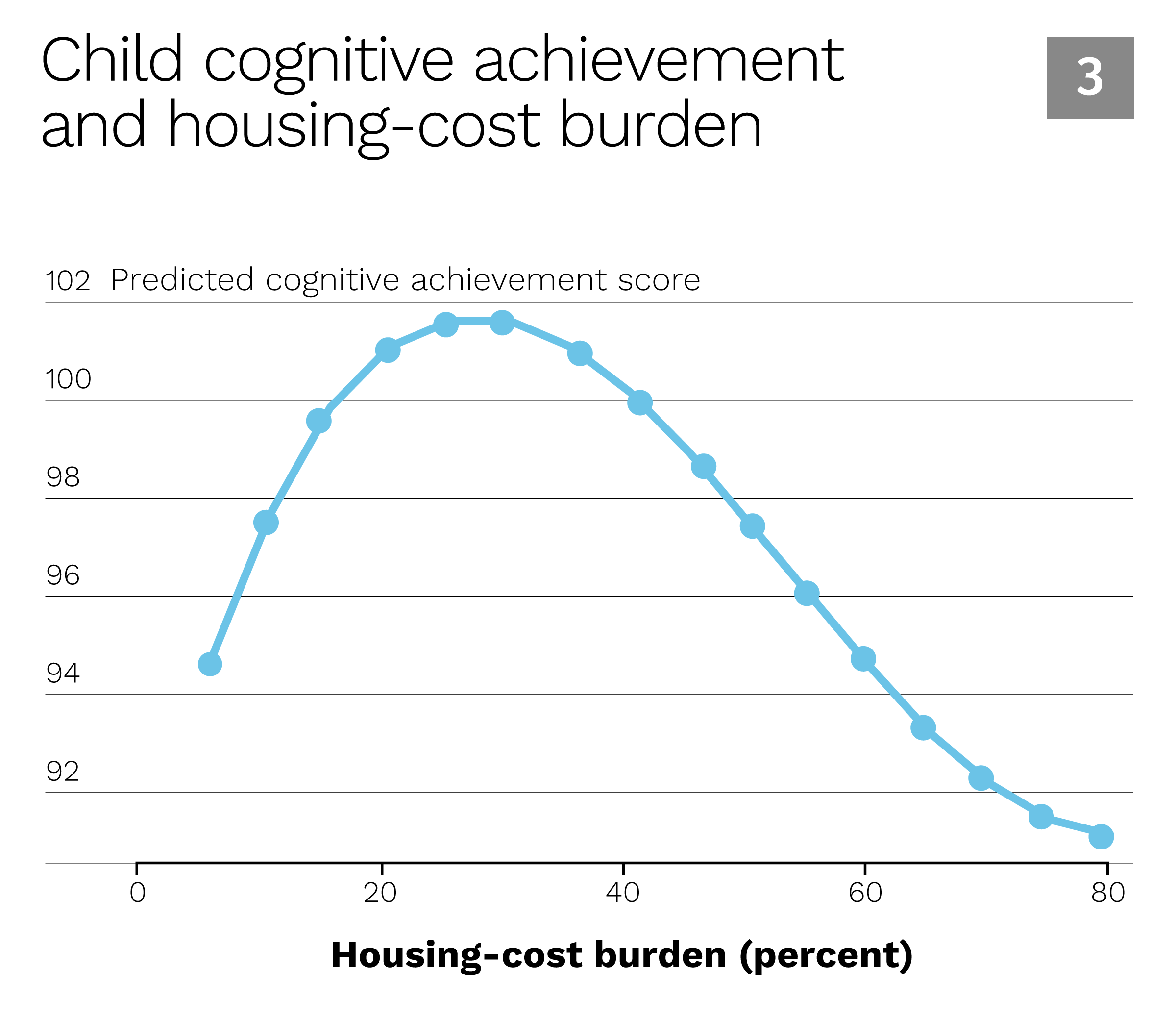

Source: Newman and Holupka (2015), used by permission of the author

Note: Sample includes 688 children from families whose incomes were less than or equal to 200 percent of the federal poverty level for 50 percent or more of the child’s life. Predicted cognitive achievement score is the predicted applied problems score from the Woodcock-Johnson (W-J) Revised Tests of Achievement, estimated using an instrumental-variable model. The W-J applied problems test measures a child’s abilities to analyze and solve practical math problems. A higher score indicates better math skills. Housing-cost burden is the percent of household income spent on housing costs. For owners, housing costs include mortgage principal, mortgage interest, property taxes, homeowners insurance, and out-of-pocket utility costs (electricity, fuel, water, and sewer). For renters, housing costs include rent and out-of-pocket utility costs.

A major motivation for expanding housing access in growing cities is to ensure that more Americans can live where economic growth is strong. Conference panelists pointed to the importance of local economic opportunity while noting that significant barriers to relocation exist.

Changing geography of economic opportunity

Morris Davis (Rutgers) and Susan Wachter (University of Pennsylvania) both noted that the geography of economic growth has changed markedly. Davis pointed to a global phenomenon: Many large cities have seen the cost of housing rise significantly over the past several decades. The fact that this pattern is not unique to the United States suggests that macroeconomic changes may be an important contributing factor. In particular, Davis points to new technologies that change where and how goods and, increasingly, services are produced. He cautioned that such factors are unlikely to reverse anytime soon.

Consistent with a role for these types of changes, Susan Wachter showed that housing costs are increasing faster in metros with more employment growth. Rents and home values have both risen more in metros in the top half of employment growth. This divergence has been more pronounced in cities with stronger economic opportunities. Wachter’s calculations show that in 1980, the top 10 metros by earnings had house prices 25 percent above the national average. By 2016, this gap had grown to three times the national average.

Impacts of housing access on families

These changes in affordability and opportunity translate into meaningful impacts on U.S. families. Sandra Newman (Johns Hopkins) focused on how housing affordability challenges for families can affect child health and well-being, and thereby extend these challenges to future generations. Newman’s work shows that the impacts of housing affordability on children are complex. Families spending both too little and too much on housing, relative to their income, see lower cognitive scores for their children that are meaningful when compared with other known predictors of such scores, as shown in Figure 3. Supporting families with subsidized housing—a policy solution for families spending too much—can have unintended as well as intended effects on children. Some children see test score benefits, others not, with significant gains for children with higher base scores and losses for those with initially lower scores (Newman and Holupka 2017). Ongoing work will examine health impacts of subsidized housing on children, but early evidence suggests that such housing provides health benefits to children (Boudreaux et al. forthcoming; Fenelon et al. 2018).

Related work by Marcus Casey (University of Illinois at Chicago/Brookings) shows that instances where wages for lower-skilled workers have not kept pace with housing costs have led to economic and racial sorting. Central city neighborhoods are increasingly white and wealthy, while poor and minority residents are pushed to less desirable urban and suburban neighborhoods (Casey et al. 2019). Lower-income residents who are displaced to older, inner-ring suburbs face higher commuting costs—in both time and money. The inner-ring suburban jurisdictions often lack a sufficient tax base to maintain aging infrastructure, fund high-quality schools, and provide social services.

Newman’s and Casey’s research connects to ongoing efforts to extend and evaluate the well-known Moving to Opportunity (MTO) study of the late 1990s. An important second-wave study, Creating Moves to Opportunity (CMTO), builds off insights from MTO and work documenting opportunity neighborhoods by Chetty et al. (2014). The research partnerships leading these efforts are described in the accompanying box.

3. How can cities expand housing? What are the next steps in housing policy?

In December 2018, Minneapolis made headlines by drafting a new Comprehensive Plan that allowed two-and three-family homes throughout the city. A few months later, the Oregon Legislature passed a similar bill to take effect statewide. Minneapolis City Council President Lisa Bender and Madeline Kovacs of the Sightline Institute, who conducted community engagement around Oregon’s bill, discussed the political context behind these policies with Jenny Schuetz (Brookings). They were joined by Robert Duffy, planning director for Arlington County, Va., a pioneering community in transit-oriented development. Below are key takeaways from their conversation.

Understand the local context

Arlington overhauled the county’s land use plans in the 1980s in response to growth in Washington, D.C.’s Metro system, prioritizing high-density housing and commercial activity along transit corridors while preserving low-density residential neighborhoods elsewhere in the county. The impetus for the density component in Minneapolis’ Comprehensive Plan came from two local trends: tightening rental markets and community reflection about historic racial disparities stemming from redlining. Oregon has a long history of statewide land use planning, dating back to the adoption of urban growth boundaries in the 1970s.

Take time to engage a diverse group of stakeholders

The effort to produce Minneapolis’ Comprehensive Plan took more than two years, with city staff conducting painstaking outreach to every neighborhood. The resulting broad coalition—including racial justice advocates, tenant advocates, and environmental groups—shaped the plan’s vision and provided necessary support to elected officials. Oregon’s state Legislature had previously introduced several similar bills that failed to win approval. With each iteration, the bill’s sponsors educated voters and legislators about the underlying issues and accumulated more political support.

Political leadership is essential

In Minneapolis, both the mayor and city council president publicly embraced the Comprehensive Plan’s goals. They have invested political capital in seeing it implemented. Oregon’s House Speaker Tina Kotek was a driving force behind HB 2001. One challenge for Arlington is that the county is home to less than 4 percent of the D.C. metropolitan area’s population: Even with forward-looking policies, the county cannot solve regional housing needs. To prepare for the imminent arrival of Amazon HQ2, Arlington’s leaders are coordinating with neighboring local governments.

Language matters

Positive framing of the issue sells better (e.g., “legalize apartments” instead of “ban single-family-only zoning”).

Moderated discussion

Next steps in local housing policy

Richard Reeves (Brookings) and Neel Kashkari (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis) concluded the conference with a wide-ranging conversation examining the larger economic implications of expanding housing supply.

When asked about addressing the housing affordability crisis, Reeves and Kashkari agreed that all levels of government must take part. Housing affordability-related problems vary across people and places, necessitating both local and federal action. Reeves argued that housing tax breaks that primarily benefit upper-middle-class families should be eliminated. “All of that money could then be reallocated into much more support for low-income subsidies,” he said. “Very low-income people … don’t actually have an affordability problem; they have an income problem,” Kashkari noted. “The solution for them is likely going to be subsidy oriented, going to states or the federal government. But for everybody else, that’s not the solution … [because] you can’t tax the middle class to then subsidize the middle class.”

Kashkari argued that high housing prices, often attributable to a lack of zoning reform, can reduce the competitiveness of local economies. He clarified that higher housing prices don’t necessarily equate to an affordability crisis. “Half of the decrease in affordability for housing is because we’re demanding bigger homes,” he said. “That is not a public policy problem.” Kashkari emphasized that serious public policy problems around housing do exist, but that it is important to be exact in identifying them.

A theme throughout the conversation was the importance of ensuring that people have options: options for communities to live in, options for career paths, and so on. The housing crisis restricts these options along multiple dimensions. “A lot of people worry about economic competitiveness and effective markets … [while others worry about] inequality and opportunity hoarding and social mobility,” Reeves said. “The Venn diagram puts housing in the middle.”

In the end, it’s not just an affordability crisis. It’s an opportunity crisis.

Lessons from research partnerships

Research partnerships, which combine the expertise of practitioners and academics, can be essential to understanding the effects of bold policies. The conference showcased two innovative research partnerships.

The CMTO program is an ongoing research partnership that provides housing vouchers and customized moving assistance to families with children in Seattle and King County to move to neighborhoods identified as high-opportunity. Christopher Palmer (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and Sarah Oppenheimer (formerly of the King County Housing Authority) explained how the partnership works and discussed early findings. Using a randomized controlled trial design, the team found that over 50 percent of families in the CMTO treatment group moved to high-opportunity neighborhoods, compared with only 14 percent of families who received vouchers alone.

The Santa Clara County rapid rehousing program provides immediate, temporary housing services to homeless single adults. David Phillips (Wilson Sheehan Lab for Economic Opportunities (LEO) at the University of Notre Dame) and Ky Le (Santa Clara County’s (SCC) Office of Supportive Housing) discussed plans for their partnership to evaluate the impact of rapid rehousing using the fact that funds already prevent SCC from serving all those who seek it.

The panelists highlighted some of the lessons they learned and offered some advice for other partnerships. The CMTO academic and practitioner teams found that their back-and-forth communication was extremely valuable for the success of the partnership. Oppenheimer noted that the teams spent a full year meeting with stakeholders to determine the most effective intervention. Palmer said that the communications between the teams made the “research much more relevant and impactful right away.” Le said that partnering with a mission-aligned organization like LEO was critical. Phillips emphasized the importance of identifying the right partner: one who is willing to listen and adjust. These research partnerships provide important examples of how to achieve evidence-based policymaking, especially at a time when demand for such policymaking is increasing.

Disclaimer: This is a publication of the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. The views expressed herein are those of Institute staff and others who contributed to the conference. They do not necessarily reflect the views of, and should not be attributed to, the Federal Reserve System or its Board of Governors or the Federal Reserve Banks.

Endnote

1 This brief was authored by conference co-organizers Jenny Schuetz and Abigail Wozniak, along with Zachary Swaziek. Schuetz is with the Future of the Middle Class Initiative at the Brookings Institution; Wozniak and Swaziek are with the Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Full conference materials and video are available at https://www.minneapolisfed.org/institute/conferences.

References

- Acolin, A., and S. Wachter. 2017. “Opportunity and Housing Access.” Cityscape 19(1): 135-50.

- Boudreaux, M., A. Fenelon, N. Slopen, and S. J. Newman. Forthcoming. “Childhood Asthma and ER Use after Entry into Federal Rental Assistance.” JAMA Pediatrics.

- Casey, M., B. Hardy, D. Muhammad, and R. Samudra. 2019. “EITC Expansions and Spatial Inequality: Evidence from Washington, DC.” Manuscript. University of Illinois at Chicago.

- Chetty, R., N. Hendren, P. Kline, and E. Saez. 2014. “Where Is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(4): 1553-1623.

- Davidoff, T., A. Pavlov, and T. Somerville. 2019. “Not in My Neighbour’s Back Yard? Laneway Homes and Neighbours’ Property Values.” Manuscript. University of British Columbia.

- Fenelon, A., N. Slopen, M. Boudreaux, and S. J. Newman. 2018. “The Impact of Housing Assistance on the Mental Health of Children in the United States.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 59(3): 447-63.

- Gyourko, J., A. Saiz, and A. Summers. 2008. “A New Measure of the Local Regulatory Environment for Housing Markets: The Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index.” Urban Studies 45(3): 693-729.

- Gyourko, J., and R. Molloy. 2015. “Regulation and Housing Supply.” In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, Vol. 5, ed. G. Duranton, J. V. Henderson, and W. C. Strange, 1289-1337. Elsevier.

- Ihlanfeldt, K. R. 2007. “The Effect of Land Use Regulation on Housing and Land Prices.” Journal of Urban Economics 61(3): 420-35.

- Jackson, K. 2016. “Do Land Use Regulations Stifle Residential Development? Evidence from California Cities.” Journal of Urban Economics 91: 45-56.

- Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) of Harvard University. 2019. “The State of the Nation’s Housing 2019.”

https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_State_of_the_

Nations_Housing_2019.pdf. - Lewis, P. G., and N. J. Marantz. 2019. “What Planners Know: Using Surveys About Local Land Use Regulation to Understand Housing Development.” Journal of the American Planning Association 85(4): 445-62.

- Mast, E. 2019. “The Effect of New Market-Rate Housing Construction on the Low-Income Housing Market.” Upjohn Institute Working Paper 19-307. Kalamazoo, Mich.: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

- Newman, S. J., and C. S. Holupka. 2015. “Housing Affordability and Child Well-Being.” Housing Policy Debate 25(1): 116-51.

- Newman, S. J., and C. S. Holupka. 2017. “The Effects of Assisted Housing on Child Well-Being.” American Journal of Community Psychology 60(1-2): 66-78.

- Romem, I. 2016. “Has The Expansion of American Cities Slowed Down?” May. BuildZoom. https://www.buildzoom.com/blog/cities-expansion-slowing.

- Saks, R. E. 2008. “Job Creation and Housing Construction: Constraints on Metropolitan Area Employment Growth.” Journal of Urban Economics 64(1): 178-95.

- Schuetz, J. 2019a. “Cost, Crowding, or Commuting? Housing Stress on the Middle Class.” May. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/cost-crowding-or-commuting-housing-stress-on-the-middle-class/.

- Schuetz, J. 2019b. “Is Zoning a Useful Tool or a Regulatory Barrier?” October. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/is-zoning-a-useful-tool-or-a-regulatory-barrier/.

- Zabel, J., and M. Dalton. 2011. “The Impact of Minimum Lot Size Regulations on House Prices in Eastern Massachusetts.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 41(6): 571-83.

Abigail Wozniak is vice president and director of the Bank’s Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute.