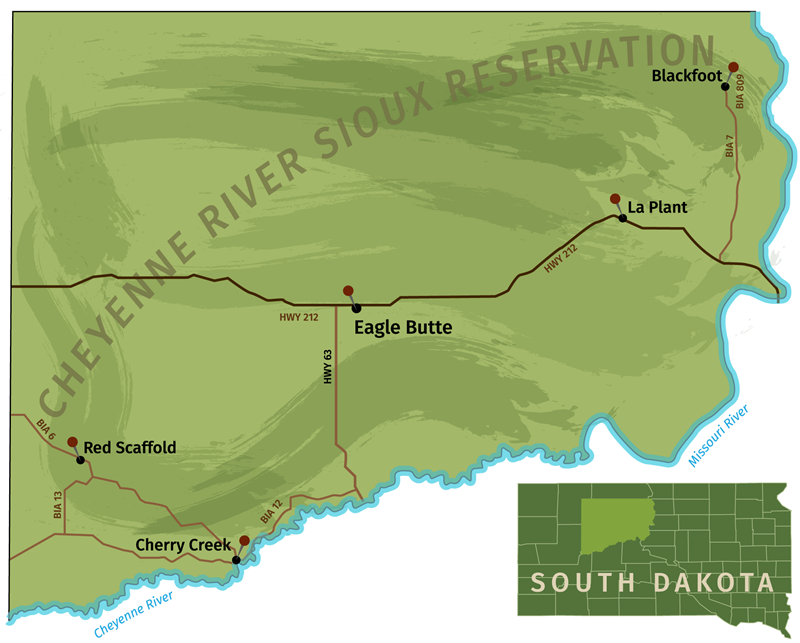

For people in remote towns on the 2.8 million-acre Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in north central South Dakota, making a court appearance means finding a way to travel up to 160 miles round-trip to the town of Eagle Butte, where the tribal court center is located. If they have no vehicle, no gas money, or no means of paying someone to drive them—a common scenario in a chronically impoverished community where per capita income is roughly $8,000 a year—they will fail to appear in court and then be fined for contempt. If there are subsequent summonses, the scene will likely repeat and repeat until the accumulated fines amount to many hundreds of dollars. It can escalate into a seemingly hopeless situation.

“This is not justice,” says Kimberly Traversie, a director and grant writer for the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. “This is piling fine after fine on people who have no resources to pay, and it can lead to depression and other problems.”

The travel requirement isn’t just an issue for people who’ve had brushes with the law. A trip to Eagle Butte has long been necessary for addressing any legal need, including orders of protection or civil commitment, custody petitions, and divorce decrees. In other words, the sorts of matters that can strain or derail everyday life until they’re settled.

A few years ago, while researching means of improving access to justice on the reservation, Traversie came across an innovative idea from developing countries such as India, Guatemala, and Nigeria: If people can’t travel to get to the legal services they need, bring the services to them by creating a courtroom on wheels. She developed the idea into a grant proposal to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and in late 2013 learned that the tribe would receive a three-year, $714,529 grant to create the first and only mobile courtroom in the United States.

Clearing the backlog

The DOJ grant covers operating costs and staffing for a bus-based courtroom, including a tribal judge; a court clerk; a bailiff who doubles as the bus driver; and a one-year salary for a Mobile Courtroom Coordinator, who was on board throughout 2014 for the grant period’s Year One planning and implementation phase. To help determine where on the reservation the courtroom should go and what services it should offer, the tribe conducted outreach among the reservation’s 21 communities during Year One and surveyed tribal members about their preferences. Year Two of the grant, which is under way through 2015, is designated for launching the mobile courtroom and delivering legal services in three communities. In Year Three, the objective is to expand services to three additional communities. Since the grant only covered the justice-related parts of the project and not the cost of purchasing an appropriate vehicle, the tribe contributed $175,000 in order for a custom outfitter in Sedalia, Colo., to convert a bus—technically, a truck chassis with an extended, 33-passenger cab—into a functional courtroom space.

Since hosting its first legal proceedings in February 2015, the mobile courtroom has already surpassed its Year Two objective of visiting three communities. Every Friday, it parks in a prominent location in one of four reservation towns identified through the survey process as being the most cost-effective places to stop: La Plant, Red Scaffold, Blackfoot, and Cherry Creek. Visits are promoted in advance through fliers and through direct communications with tribal members who have business before the court. They’re given the option of setting up their legal appointments on the bus or in Eagle Butte, and according to Chief Judge Brenda Claymore, use of the bus is gradually catching on.

“Initially, when we offer people the bus option, their reaction is, ‘Really? I think I’d better just stick with going to Eagle Butte,’” she says. “They’re skeptical, because this is so new. But then later they call and ask to be rescheduled to come to the mobile court in their community.”

One top priority for the initiative is to start clearing a tremendous backlog that has built up over the years because of tribal members’ inability to appear in Eagle Butte to resolve their cases. The docket on the bus includes the backlog plus a host of other matters, such as misdemeanors, small claims, and truancy. For criminal cases, the mobile courtroom holds arraignments only, not trials, and it sticks to proceedings tied to “victimless crimes”—low-level offenses where there’s no security risk related to having a victim and perpetrator together in a confined space.

Another top priority is to put a positive face on tribal justice, so tribal members who may have had negative experiences with the system will begin to view it as something other than punitive. Traversie notes that such a change in perception would align with the tribe’s traditional philosophy of justice, which she characterizes as rehabilitative and therapeutic.

Everyone who receives services on the bus is asked to complete a satisfaction survey, the results of which will be used to gauge the project’s progress and make improvements as needed. According to Claymore, information on total cases heard or individuals helped isn’t available yet, since the initiative is still getting established, but those figures will be included in a report to the DOJ after Year Three.

An expansive vision

Federal financial support for the mobile courtroom will run out when the three-year grant period ends, but Traversie is hopeful about finding other funding sources to keep things going.

“The DOJ’s rules prohibit us from being funded for exactly the same purpose twice, but there are other justice-related grants we can apply for,” she explains. She and Claymore envision expanding the tribe’s mobile justice services to include court-ordered drug and alcohol treatment, probation monitoring, and even traditional Lakota peacemaking circles.

Traversie is also hopeful that the initiative will serve as a model for other communities that struggle with access-to-justice issues related to poverty and distance. “This would be easily replicable in different jurisdictions, to fit a different tribe or even just a different county. These are issues that happen in rural America all the time.”

For now, the only mobile courtroom in the country is helping people take concrete steps to settle disputes, resolve pressing personal matters, and conserve scarce financial resources. In Traversie’s view, the sum effect of those resolutions and actions is a stronger community.

“This contributes to the well-being of our people,” she says. “We can’t expect everyone to live in Eagle Butte. People want to live where they’re from, and we want to make it possible for them to do that comfortably. Because they don’t have the financial resources to make it to their court date, we did this instead, to lessen their economic and financial burden. To make life livable.”