Video: fedgazette Editor Ron Wirtz on temporary employment

Gauher Mohammad vividly remembers the day he got his start in the staffing services industry.

It was Sept. 10, 2001, and Mohammad was the service manager of a local Doherty Staffing Solutions office in Owatonna, Minn., about an hour south of the Twin Cities in southeastern Minnesota. The industry had been seeing strong growth, and Mohammad was eager to be a part of that growth.

But a day later, terrorists hit the World Trade Center and everything changed, with orders for temporary workers grinding to a quick halt, said Mohammad. “I thought to myself, ‘Why on earth did I take this job?’”

The answer would become clear over the next dozen years, though not without significant trials. Today, out of his Owatonna office, Mohammad oversees operations and service functions for the entire southern Minnesota market for Doherty. In this position, he’s experienced the roller-coaster highs and lows of two recessions.

Business rebounded after the 2001 recession, and the industry “lived the good life” through the middle part of the decade, only to see a crash again during the Great Recession, said Mohammad. But from the depths of recession, the industry has risen to new heights. “In the last three years, things have grown tremendously,” he said.

Doherty has 16 offices throughout Minnesota and another eight offices located on the premises of regular Doherty clients. The staffing firm grew slowly at first coming out of the Great Recession—about 3 percent annually in 2010 and 2011, according to company figures. But 2012 saw 34 percent growth, and through October of 2013, business was up almost 18 percent. The company places about 3,400 workers a day with clients.

Growth has also been robust at other staffing agencies. Express Employment Professionals has staffing offices in every state in the country, including more than 50 in Ninth District states. From 2010 to 2012, Express nearly doubled the annual number of unique workers it placed with clients in district states, reaching almost 32,000, according to figures from Jim Johnson, an owner of three Express offices in the Twin Cities.

The drivers of this growth are myriad and evolving. The most basic source of expansion is employers’ need for a flexible workforce “to add workers when demand for their goods and services is high” and cut back to a core staff when demand is lower, Johnson said. “This is a cost-efficient way to manage a workforce.”

Uncertainty also plays a big role. Even as the economy grows, more employers are hiring temporary rather than full-time employees because they are not confident in the future economy, having been chastened by the worst recession in 75 years. Many sources also said that political controversies and federal fiscal policy have compounded that uncertainty.

The strong growth of recent years has pushed the industry near its historical employment peak, and most signs point to significantly more workers and employers using staffing services going forward, in part because both hirers and the hired have come to recognize the industry’s matchmaking advantages.

Juan Speilman started with Award Staffing in April 2013.

Photographed at The Bernard Group in Chaska, Minn.

Will work for three months

The staffing services industry has been around for decades. But its modern form started to take shape in the 1990s, when manufacturing saw a mild renaissance and introduced the concept of just-in-time production, which brought with it a need for just-in-time labor. The move also proved to be good public relations for manufacturers by allowing them to avoid negative publicity related to permanent layoffs when business sagged.

The industry continues to grow as more employers and industry sectors embrace the utility of temporary workers. “It used to be you’d have a Kelly girl in because you had a vacation” to cover, said Jon Osborne, vice president of research and editorial at Staffing Industry Analysts (SIA), located in Mountain View, Calif. Today, temps “are more integrated with the regular workforce. ... They are not a side issue anymore. They are a central issue.”

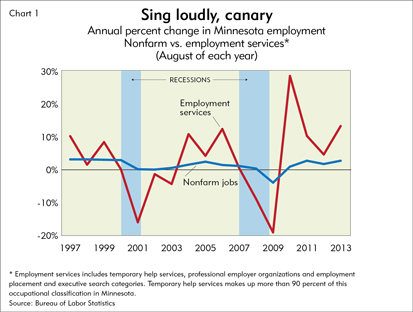

In the process, temp workers have become a canary in the economic coal mine, because temp workers are often the first employees cut when business gets tight. “We start to see changes in the economy about 18 months ahead” of the rest of the economy, said Roxie Loftesness, owner of AvailAbility, with offices in Sioux Falls and Brookings, S.D.

The industry decline started in 2006. By October 2008, in the midst of the collapse in the financial sector, “the door came down, like someone shut the lights out. You could just feel it,” said Loftesness, who estimated that her hours booked (a standard industry metric) dropped by half.

Data show an employment trend seemingly in fast-forward mode. The staffing industry is considered not only pro-cyclical, but hyper-cyclical because temporary and contract jobs “are especially sensitive to the ebbs and flows of the economy,” according to the American Staffing Association (ASA).

In terms of government data, temp jobs fall under the broader category of employment services, and temp jobs make up about 90 percent of this job category. Over the course of the 18-month Great Recession, staffing firms nationwide lost about 1.1 million jobs—or about one-third of their workforce.

In Minnesota, the sector has seen volatile job loss leading into recessions, followed by strong growth out of them. (See Chart 1. Also see nearby sidebar for a description and breakdown of the employment services sector and temporary job trends in Ninth District states. Due to a lack of more detailed industry data in some other Ninth District states, the majority of district-level trends will be profiled through Minnesota, which has the largest number of temp workers.)

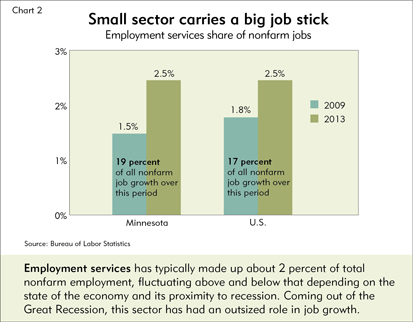

Since the recession ended, the employment services sector has roared back, accounting for more than 17 percent of net employment gains nationwide. Among some district states, the effect has been even larger—19 percent in Minnesota, for example (see Chart 2). This for an industry with a tiny fraction of total jobs. Since the end of the recession, the share of jobs in employment services has grown from about 1.5 percent of total nonfarm employment to 2.5 percent.

The staffing services industry now sports about 3 million jobs nationwide—back to its 2006 peak—but that figure underestimates the industry’s penetration because it represents average daily employment. For most industries, this count is roughly equal to annual employment. But the short-term nature of most temporary jobs means that many more workers cycle through the industry on a regular basis. Based on a count of W-2 forms, the ASA estimates that staffing firms hired 11.5 million temporary workers during 2012. That figure was expected to rise above 12 million in 2013.

LaRea Eshelman started with Award Staffing in December 2013.

Photographed at The Bernard Group in Chaska, Minn.

Temporary drivers

Along with cyclical factors, there are some other, more circumstantial sources behind the growth of temporary employment since the recession.

Loftesness, from AvailAbility, said action (and inaction) by the federal government on things like budget and tax issues, health care insurance and the debt ceiling “have really caused a lot of uncertainty. You see businesses not take the steps you would have expected. ... People say they can’t move ahead like they would want.”

Among these factors, most sources pointed to the Affordable Care Act as the uncertain elephant in the room. “Business still does not have any idea of the [ACA’s] effect” on their business long term, Loftesness said. “Get the crystal ball out because no one knows where it’s going to end up.”

As a result, flexibility is a catchword for many employers dealing with nagging uncertainty. “Companies feel the need to be as flexible as possible,” said Tim Doherty, CEO of Doherty Staffing Solutions. Companies “don’t want to go out and add full-time employees given the possibility of having to go through the gut wrench of layoffs” if business tapers off in the future, Doherty said.

David Dietz, president and CEO of Preference Personnel in Fargo, N.D., pointed out that for many manufacturers, production is often seasonal and “most private sector employers are running leaner than prerecession, [and that] is contributing to this flexible workforce demand.”

Truth Hardware is a manufacturer of hardware for windows and doors, and a Doherty client. About 90 percent of its labor force of roughly 625 is located in Owatonna. As a supplier to the U.S. and Canadian housing industries, the company sees “extreme seasonality. ... We go from X production to two times X,” with peak demand in summer and early fall followed by “a precipitous decline,” said CEO Jeff Graby.

The company has roughly 80 temp workers, but headcounts can rise as high as 110 and fall as low as 45 depending on orders. Temp workers perform “similar work to full-time workers,” including both entry-level assembly and some skilled trade. Because of heavy seasonality, “it would be a tremendous challenge to manage [production], and temp workers currently are an important bridge to managing” seasonal variation, Graby said.

Many employers, especially those in manufacturing, follow an 80-20 or 90-10 rule: The bulk of an employer’s labor force consists of full-time, permanent workers, and the remainder is temporary or “contingent.” A September SIA survey of firms using contingent workers showed that the average share of such workers was 16 percent in 2012, a 1 point rise from a year earlier. The survey projected that the share would rise to 18 percent in 2014. Certain sectors are already much higher, like technology and telecomm industries (23 percent), according to the survey. It also found that “no category of buyer expects a decrease in the contingent proportion of their workforce. Buyers are generally bullish about hiring most types of labor.”

Viracon, a manufacturer of architectural glass and other products, came somewhat late and reluctantly to temp staffing in 2008 after business plummeted with the recession. The company had to lay off hundreds of workers at three plants, including its largest in Owatonna, according to James Wendorff, company vice president of human resources.

The layoffs, Wendorff said, “were very difficult. It’s expensive, emotional, painful and all that.” When the time came to hire more line workers, “frankly, we were gun-shy. We were not confident” about hiring permanent employees and keeping them busy. So Viracon turned to Doherty for 50 temporary workers.

“Historically, as an HR person, I’ve not really bought into the [temp] model, but we thought we had no choice,” said Wendorff. The company hired entry-level workers, mostly for materials handling, and “sprinkled” them into the company’s production lines, which he acknowledged created some challenges. Glass handling and safety requires training, for example, which is more difficult when temp workers might not be there a month later. But, Wendorff said, “we’ve worked through issues without a hit to productivity.” The company now has about 150 temp employees out of 900 total production workers, and total headcount at the Owatonna plant is back to about 1,400.

Wendorff has become a grudging convert to the use of flexible staffing. Though he still prefers direct hiring, using temp workers “has been very successful.” A Doherty representative works onsite handling many of the HR functions, such as recruitment, interviewing and additional vetting of work candidates, filling out paperwork and other activities. “From my [human resources] paradigm, I didn’t want to do it. But the Great Recession kind of reset my thoughts,” he said.

Donald Nunley of Eagan, Minn., has been working for Express Employment Professionals at Renewal by Andersen in Cottage Grove, Minn., since October 2013.

Worker shift?

But strong employer demand for temp workers cannot assume an endless supply of such workers. Some companies may be able to achieve perfect elasticity in their workforce when unemployment is high. Whether they can do that in tighter labor markets remains to be seen. Staffing agencies and employers contacted for this article reported a clear and fairly recent decline in the temporary labor pool, in terms of numbers and available skills.

This fall, Doherty had 1,000 unfilled openings—or more than 20 percent of all job orders, according to CEO Doherty. “Compared to a year ago, [lack of labor availability] is dramatic.”

This is particularly evident in Doherty’s Owatonna office. After the recession, unemployment in the city and surrounding Steele County hit 10 percent, and “people were walking in here looking for a job,” said Mohammad. The county unemployment rate now sits below 5 percent, thanks mostly to growth in the county’s large manufacturing base, which accounts for 26 percent of all private employment, double the state average. Now Doherty Staffing is beating the bushes trying to find people interested in temp assignments.

Every day, Mohammad’s office sends 1,000 to 1,200 workers to its clients throughout southern Minnesota. “Our challenge is to find people to fill the 300 positions that are open” but unfilled, said Mohammad. Some firms have standing orders for workers, some of which are re-upped as soon as existing labor orders are filled. “Finding people is the biggest challenge. ... We have been unable to bring openings down to 50, and that’s a lot of lost revenue.”

Mohammad’s annual recruiting budget has been more than sufficient in the past to keep the new-worker pipeline full. Not any longer. “I blew through my recruiting budget [in 2013]. I had to go back to Tim [Doherty] to ask for more money.”

Your lever, Mr. Worker

Of course, not all areas are enjoying low unemployment rates. But many metro regions and smaller regional centers in the Ninth District are. And where labor is getting tight, workers appear to be gaining some leverage they haven’t had since before the recession, like greater say over work schedules and conditions, sources said.

The surest sign of worker leverage is higher wages. Wages for temp workers are generally (though not universally) comparable to those of similar permanent positions, according to most industry sources. However, total compensation including benefits for temp workers is widely believed to be lower; what employers pay staffing firms for their service is usually recovered in the benefits they no longer provide for these workers. One manufacturing source said the cost mostly comes out in the wash. “It’s even-steven.”

But tracking wages in this sector is difficult, particularly in real time or at regional levels with varying degrees of unemployment. Government data also do not distinguish wages for similar temporary and permanent jobs. Figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) suggest that temp wages in district states started to grow in 2012 (the most recent figures available), particularly in the Dakotas; wages increased by almost 10 percent in North Dakota in 2012 (see Chart 3).

However, evidence of rising wages is harder to come by in the field. “There is a huge reluctance to raise wages” among firms because they are unsure if they will be able to pass those costs along to their customers, said Doherty. The firm’s 1,000 unfilled job orders result not so much from a lack of job seekers, but because job seekers are unwilling to accept jobs at prevailing wages, which Doherty characterized as between $10 and $15 an hour. He said wages have risen very little since the recession despite the fact that unemployment in Minnesota has fallen considerably.

Staffing firms also cannot raise wages to attract more workers unless those higher wages can be charged back to clients, and that’s a tough sell in the current economy. For employers, the idea of paying higher wages runs headlong into the reality of competition.

Wendorff, from Viracon, acknowledged the importance of wages in finding qualified workers, but said the company’s hands were tied. “We’ve looked at wages hard. There isn’t an employer that doesn’t want to pay $30 an hour.” He added that industry competition dictates wage rates and that “moving from $11.70 to $12 is not going to make that much of a difference. You have to make a big move,” and that wasn’t feasible for the company.

Most staffing executives said higher wages were critical for recruiting a qualified workforce in 2013. While employers once held a superior negotiating position, Doherty believes that the pendulum has swung in favor of workers. In 2014, he said, “workers are going to have the opportunity to be more choosy and be able to dictate higher wages.” Mohammad, the Doherty manager in Owatonna, agreed. “If companies don’t make adjustments, they are not going to find the talent.”

Loftesness, in Sioux Falls, said she is seeing wage compression from the bottom up, with wages for lower-paid, entry-level positions rising and differences between base wages and shift pay narrowing. She said she hasn’t seen a lot of change in the number of unfilled openings, “but they are taking longer to fill,” in part because unemployment in the region is hovering near 3 percent, and workers can afford to be more selective and footloose. “It’s a challenge. People are more likely to leave their job. In the past, people would stay put. That’s starting to loosen up.”

With other options available, SIA’s Osborne noted that “temps have no loyalty. You have to treat them well to keep them.” Employers, therefore, “will have to pay more if the pool of available workers prefers not to take those jobs.”

Elizabeth Safeski of Edina, Minn., has been working for Express Employment Professionals at Eide Bailly in downtown Minneapolis since October 2013.

Foot in the door

At the same time, workers might continue seeking temp jobs if there are good linkages to permanent employment. The trends here, as they are for wages, are difficult to discern. Staffing agencies have long been involved in so-called temp-to-perm assignments that put workers in temporary jobs with the prospect of gaining a permanent job. Sources likened the process to “dating before marriage” or an “on-the-job interview.”

Temp-to-perm is a useful personnel strategy for employers because traditional vetting through applications and interviews only reveals so much about a worker. Getting a candidate as a temporary employee allows a firm to gauge productivity and overall performance that are very difficult to ascertain in an interview. Mohammad said all of his clients use Doherty to manage their labor needs over the long term. “I can’t remember the last time [a client] needed someone for three weeks and was done.”

Wendorff, from Viracon, said temp-to-perm gives both workers and employers “a chance to kick the tires.” The Viracon plant “rolls” over temp workers every 90 days, with some coming back, but with virtually no one on long-term temp assignment. “We don’t like having temps for eight months.” When Viracon needs more permanent employees, it looks first to its temporary workforce. Given a relatively high turnover rate, especially for entry work, there are a fair number of opportunities, and Wendorff estimated that the company has hired 150 permanent workers who came in through the temp door.

This vetting process is also good for workers, three-quarters of whom are seeking permanent jobs, according to SIA’s Osborne. Permanent placements rates vary by the type of work, but on the low end, the rate is about 30 percent. The average job tenure is about three to four months, which means chances are “quite good” that if you can string together three jobs, “things will work out for you in finding permanent employment if you’re playing the odds.”

Whether fast-growing temp jobs, combined with temp-to-perm efforts, are facilitating a more rapid recovery in full-time employment is difficult to say. Sluggish growth of full-time jobs overall—in the face of rapidly rising temp jobs—suggests that the industry’s effect on full-time employment has been mild, or worse. However, this ignores what would have happened if the industry had grown at more normal levels and employers were left to add to payrolls in the more traditional fashion.

Anecdotes, for their part, are mixed. On the plus side, Doherty said his firm is seeing more permanent placements, and the Wisconsin Association of Staffing Services reported that 86,000 employees leveraged their temporary job into permanent employment—about one in every six (gross) job gains that year.

But not everyone is seeing more temp-to-perm placements. Jerome Gerber is vice president for Award Staffing of Bloomington, Minn., which has three staffing offices in the Twin Cities placing workers in industrial, technical, hospitality and other positions. Gerber said that only about 25 percent of Award’s temp workers were landing full-time jobs, and that figure has trended down the past two years, with workers waiting longer for permanent offers. He added that he’s seen “a significant number of companies make the decision to have long-term temporary assignments versus temp-to-hire arrangements in order to protect themselves from what they fear will be the negative impacts of the Affordable Care Act.”

Johnson, with Express in the Twin Cities, said more than 40 percent of Express temp workers transition to full-time, permanent workers. While that’s above the industry average, “previously, we were seeing 60 percent of our workers go full time,” Johnson said. “Companies are cautious with full-time employees because there is still so much indecision” because of federal policies and compounded by an uneven economic recovery.

A game of pairs

All of these factors are pushing further evolution in staffing services. The industry grew up filling job slots for short periods. But it now sees itself as a strategic long-term partner, aligning the needs of both clients—employer and employee—in an economy that has a simultaneous surplus and deficit of labor, strong demand for both jobs and workers in some sectors, and a need for better matchmaking.

For example, much attention has been given to a so-called skills mismatch—namely, that job openings go unfilled while jobless people remain unemployed because their skills don’t match what employers are looking for. As workers fail to find jobs, as one source put it, “weeks turn to months, [and] job seekers get discouraged and leave the workforce.”

Many believe this is where the real opportunity lies for the staffing industry—to play a greater “coupling” role connecting the pipeline of available workers to labor-seeking employers, particularly those using temp workers as a test ground for their permanent workforce.

The industry still has a lot of room to grow, Osborne noted. “Large companies are just learning how to use [temp workers] effectively. Many think, ‘Oh, temporary labor?’ I didn’t think I could do that.’ ... A lot of [firms] don’t know about it that I think should.”

The same could be said for workers, many of whom see staffing firms as a last resort rather than a first option when they’re job hunting. One myth Loftesness said she constantly has to battle is that “people think they have to pay us to find them a job.” In reality, “people can have their own HR department and not have to pay for it.”

But for the industry to expand its matchmaking abilities to more workers, it will have to address some ingrained, negative impressions in the workforce—that it has mostly part-time, dead-end jobs with low wages, no benefits or sick days and little opportunity for people to develop new skills or advance their careers.

In fact, many staffing firms offer medical and retirement benefits. Industry sources acknowledge that such plans are typically modest, even spartan, compared to those available to permanent, full-time employees. But these benefits are often lightly subscribed among temp workers because most temp workers do not expect to be at the job long and want to maximize their take-home pay. Getting benefits like health care and retirement plans “is not why people get temp jobs. People want cash” to pay the mortgage and car loan, with the eventual hope of catching on somewhere permanently with full benefits, said SIA’s Osborne.

Nonetheless, a perception hangs over the industry that it does the dirty work for unscrupulous employers out to take advantage of workers, particularly low-skill workers doing day labor and other menial tasks who often don’t have good job alternatives. Industry sources, like Loftesness, acknowledged that “in all business, there are people who don’t represent the industry well.”

Osborne said he gets frequent media calls, and most view the industry skeptically. “Almost 100 percent are against [temp work]. They are sure it’s some form of worker exploitation.”

And some of that does occur, he said. “This is an industry with free entry. If you have a telephone and a garage you can open” a staffing agency. Given this low barrier to entry, “you will get people who are not doing things right,” Osborne said. But those are a small minority, he said. If that were not the case, workers would stop patronizing these services, especially as unemployment fell, and the resulting turnover would be costly to firms, said Osborne.

The likelihood of abuse is higher in places with ample labor supply, where workers have fewer opportunities to take their services elsewhere. But in places with low unemployment, such as North Dakota, “the extreme competitive nature of the staffing industry combined with a limited labor pool would naturally take care of the problem, I would hope,” said Dietz of Preference Personnel in Fargo.

In the end, the industry will grow to the extent that it can convince both employers and workers that it is providing a valuable service. Loftesness pointed out that “the job opportunity and people are relative.” The trick is to discover and apply worker skills that might not exactly fit the job description, but can be molded to be a good fit.

This can be especially useful to older workers, those in declining industries or those who have been out of work for a long time. These workers “don’t know how to use [and reapply] the skills they have” in a different setting, said Loftesness. “That’s where our industry is invaluable. We look at skills and work history and look at where we can transfer them” to the right company where both parties benefit. Dietz agreed: “Oftentimes an employment professional sees things in a worker that a résumé can’t do justice.”

“We all want to choose our employer,” said Mohammad. But many “don’t know what to do or where to go—‘What’s a good fit for me?’” A worker might do separate stints with different clients, or even with different staffing agencies. “We have the opportunity to provide workers with continuous employment” and to establish a work history and the skills necessary that will attract an offer for permanent work.

Raul Tornel has been with Award Staffing since January 2011. He is shown here at The Bernard Group in Chaska, Minn.

A new ceiling?

In some ways, the industry suffers a reputation worthy of an adapted Yogi Berra-ism: Nobody wants the type of job offered by staffing agencies because they only offer jobs that millions of workers are taking.

However viewed, continued growth is predicted for the industry, in both the short and long term. SIA estimates that staffing and recruiting sales will increase 6 percent in both 2013 and 2014. Through 2020, the BLS projects that employment services will grow two-thirds faster than overall employment, adding 631,000 jobs, a 23 percent increase over 2010.

In fact, the historical employment ceiling for temp workers—between 2 percent and 3 percent of employment, depending on the measure used—could possibly break in the coming years, a result of the continued soft recovery and further uncertainty about federal fiscal and other economic issues.

But many observers expect continued growth because the industry is an underutilized clearing mechanism for employers needing labor and workers needing jobs. Loftesness noted that only 15 percent of employers use staffing agencies. “We definitely think the numbers have room to grow.”

Gerber, from Award Staffing, sees the temp industry entering uncharted waters, with unprecedented growth on the horizon. “In the past, there were often direct correlations between economic indicators and the ebbs and flows of the staffing industry. Those correlations no longer exist because of the dramatically disparate drivers of growth” in the industry. In three to five years, Gerber said, “I expect the ceiling to exceed 10 percent of the workforce.”

Osborne was dubious of a 10 percent ceiling. “Not anytime soon. Overall, most people want permanent jobs because they have mortgage and car payments every month,” and a steady paycheck allows them to make those payments, said Osborne.

But he also noted that third-party job matching is growing and is finding a new niche online. Nationwide, SAI has identified 67 online-only staffing agencies—like eLance, Odesk—many of which cater to professional types not widely served by traditional staffing agencies. “It’s the fastest growing part of staffing,” said Osborne. “It’s going to be a huge deal and could increase penetration tremendously” because it gives both potential employer and worker more information and work history through ratings and other features, he said. And as more sectors of the economy understand the competitive opportunity offered by a contingent workforce, “that would take us to several more percent” of employment.

If that occurs, the United States would only be catching up to employment trends in some other countries. “Politically, the trend in our country is to be more like Europe,” said Doherty, where more stringent laws regarding hiring and firing of permanent employees has fostered a temp worker penetration rate twice that of U.S. firms.

Express Employment Professionals has more than 600 office locations in the United States, Canada and South Africa. Johnson said the company operates nearly two dozen locations in South Africa, where “roughly 7 percent of the country’s workforce is on the payroll of Express or one of our competitors. So we expect the United States to follow these global trends, and a 3 percent to 5 percent temp penetration rate in the U.S. is not unrealistic.”

Research assistants Dulguun Batbold and Bijie Ren contributed data research to these articles.

Related article: Ninth District employment services sector: Not a temporary blip

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.