Our Mission

The Community Development Department supports the Federal Reserve System’s economic growth objectives by promoting community development through fair, impartial, and efficient access to credit and related financial services. We support investment in low- to moderate-income communities through information, outreach, and technical assistance. We serve the Ninth Federal Reserve District, which includes Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, northwestern Wisconsin, and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

Introduction

This report presents the findings from a biannual survey of community organizations, including developers, lenders, and service providers, that is designed to provide insight on 17 key indicators related to the economic health of low- to moderate-income (LMI) communities. Information included in this report is based on the front-line observations of representatives of 381 organizations that play a critical role in the development and stabilization of LMI communities in the Ninth Federal Reserve District. Respondents were asked to gauge changes in employment, housing, financial, and business conditions for the communities they serve by comparing current conditions with those that prevailed six months earlier. Collectively, their observations help provide a community-based perspective on issues that are important to the community development work of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and the Federal Reserve System.

Survey respondents included: community banks, non-bank community development financial institutions, public and private economic developers; state workforce and job service centers; housing developers and housing service providers, including government agencies; small business technical assistance providers; Community Action Agencies and other organizations that provide basic-needs assistance; financial education providers; trade associations; tribal organizations; university extension services; community foundations; neighborhood organizations; and other nonprofit entities. The geographic locations of respondents were widely dispersed, representing more than 250 cities, townships, and reservation areas across the Ninth District.

| Table 1. Respondent Pool by Geographic Area | ||||

State |

Proportion of Respondent Pool |

Proportion of Ninth District Population* |

||

Michigan (UP) |

3% |

4% |

||

Minnesota |

35% |

59% |

||

Montana |

14% |

11% |

||

North Dakota |

17% |

7% |

||

South Dakota |

21% |

9% |

||

Wisconsin (NW) |

9% |

10% |

||

*Based on 2007–2011 American Community Survey five-year estimates. |

||||

Respondents were asked to gauge changes in LMI community conditions using the response categories “decreased,” “stayed the same,” or “increased.” They were also invited to elaborate on their responses by providing comments. Respondents were instructed to answer questions based on firsthand observations and were encouraged to answer “don’t know” if they were not knowledgeable about an issue in the community. For each question, those who answered “don’t know” were excluded from the analysis.

Information for Ninth District Insight was gathered through an online survey developed and administered by the Community Development Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Responses included in this report were collected during the months of December 2012 and January 2013. Seventy-nine percent of respondents participated in the previous poll conducted during the second quarter of 2012.

Percentages reported are for valid responses only, unless otherwise noted. Numbers might not equal 100 due to rounding. Caution should be used when interpreting the numbers for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan as they represent fewer than 20 cases.

LMI Economic Conditions at a Glance

In fourth quarter 2012, five indicators related to employment and business activity in LMI communities showed overall improvement Districtwide, including:

- Businesses seeking new loans or lines of credit in LMI communities;

- Business openings in LMI communities;

- Business closings and bankruptcy filings in LMI communities;

- Employment opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities; and

- Job training opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities.

Survey responses also indicate that the overall number of vacant and foreclosed properties on the market in LMI neighborhoods has decreased in comparison to six months ago.

Most indicators related to consumer credit and housing opportunities for LMI households continued to remain negative. In fourth quarter 2012, indicators that remained the most negative Districtwide include:

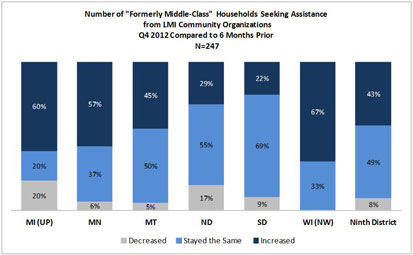

- The number of “formerly middle-class” households seeking services from LMI community organizations;

- Demand for financial counseling in LMI communities;

- Use of alternative financial service providers by LMI households; and

- LMI households’ ability to find affordable rental housing that meets their needs.

LMI Economic Index Fourth Quarter 2012 |

|||||||

The LMI Economic Index measures overall change in community conditions. The Index ranges from 0 (most deterioration in conditions) to 200 (most improvement in conditions) where a value of 100 equals neutral. A number less than 100 indicates overall deterioration and a number greater than 100 indicates overall improvement. Indicators are ordered from greatest Districtwide deterioration to least Districtwide deterioration based on fourth quarter 2012 survey responses. Index values for second quarter 2012 are provided in parentheses for comparison. |

|||||||

|

Ninth District |

MI (UP) |

MN |

MT |

ND |

SD |

WI (NW) |

Number of formerly middle-class households seeking assistance from LMI community organizations |

65 |

60 |

49 |

60 |

88 |

87 |

33 |

Demand for financial counseling in LMI communities |

67 |

71 |

59 |

65 |

80 |

92 |

37 |

Use of alternative financial service providers by LMI households |

68 |

50 |

58 |

100 |

53 |

67 |

35 |

LMI households’ ability to find affordable rental housing that meets their needs |

72 |

125 |

70 |

66 |

50 |

86 |

81 |

LMI community organizations’ confidence in ability to retain adequate levels of funding for staff and programs |

74 |

100 |

70 |

61 |

73 |

90 |

71 |

Ability of creditworthy LMI households to obtain a mortgage |

74 |

50 |

74 |

69 |

79 |

80 |

76 |

Amount of consumer debt carried by LMI households |

78 |

100 |

80 |

64 |

77 |

84 |

71 |

LMI community organizations’ ability to meet the needs of clients seeking assistance |

78 |

100 |

69 |

75 |

80 |

90 |

85 |

Ability of business owners in LMI communities to recruit and retain workers with the “right” skills |

85 |

43 |

89 |

83 |

79 |

89 |

88 |

Access to credit for business owners in LMI communities |

86 |

85 |

76 |

81 |

105 |

97 |

69 |

Proportion of LMI households seeking services that do not have a bank account |

88 |

75 |

71 |

100 |

87 |

106 |

107 |

Business closings and bankruptcy filings in LMI communities |

105 |

75 |

104 |

93 |

127 |

104 |

100 |

Job training opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities |

110 |

87 |

102 |

112 |

129 |

110 |

108 |

Business openings in LMI communities |

111 |

100 |

95 |

104 |

152 |

111 |

107 |

Number of vacant and foreclosed properties on the market in LMI neighborhoods |

116 |

57 |

113 |

103 |

150 |

113 |

103 |

Employment opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities |

116 |

78 |

109 |

127 |

137 |

100 |

132 |

Businesses in LMI communities seeking new loans or lines of credit |

122 |

85 |

125 |

96 |

136 |

119 |

132 |

How the LMI Economic Index is calculated |

|||||||

Following is an in-depth analysis of survey results, including state-by-state comparisons and illustrative quotes from respondents.

Employment Conditions

Opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers and hiring for open positions

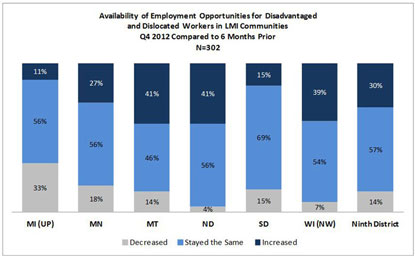

Fourth quarter 2012 survey results indicate continued overall improvement in employment opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers Districtwide, with greatest overall improvement in North Dakota and western Wisconsin. Minnesota-based respondents also reported overall improvement for the first time since tracking of this indicator began in June 2011. (See Table 2.)

According to survey responses, activity in the Bakken oil region continues to generate new jobs in manufacturing, retail, and construction. Despite an apparent increase in job openings across the District, respondents continued to report several barriers preventing employment for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities, including lack of technical and soft skills, poor credit, and competition with more educated workers that are also applying for entry-level positions. A number of respondents also expressed concern about wage stagnation and a decline in job benefits.

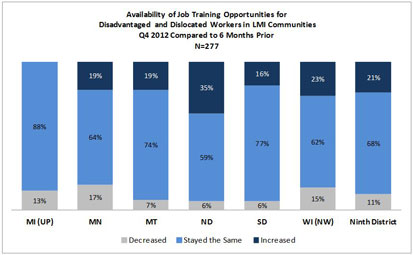

Survey respondents reported slight overall improvement in the availability of job training opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities; however, many reported a need for more, citing an unmet demand for skilled manufacturing workers.

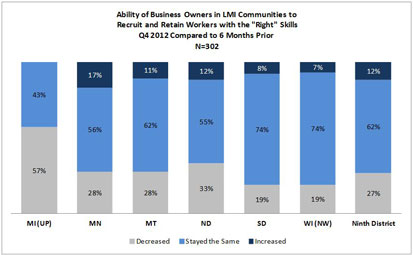

When asked who is being hired for available jobs “in most cases,” only 41 percent said workers with skills equal to the posted requirements. The direction of skills mismatch was highly correlated with geography, with respondents in urban areas reporting frequent hiring of employees with skills higher than the posted requirements and those in rural areas reporting frequent hiring of employees with skills lower than the posted requirements.

Some respondents reported that employers in their community are choosing to leave positions unfilled rather than hire less-qualified workers. A number of respondents across the District also cited the extension of long-term unemployment benefits as a barrier to filling open positions.*

| Table 2. LMI Economic Index, Q2 2011 to Q4 2012 Employment Opportunities for Disadvantaged and Dislocated Workers |

||||

Geographic Area |

Q2 2011 |

Q4 2011 |

Q2 2012 |

Q4 2012 |

Michigan (UP) |

50 |

63 |

83 |

78 |

Minnesota |

60 |

68 |

99 |

109 |

Montana |

67 |

92 |

118 |

127 |

North Dakota |

107 |

132 |

150 |

137 |

South Dakota |

89 |

106 |

107 |

100 |

Wisconsin (NW) |

76 |

85 |

106 |

132 |

| Ninth District | 73 |

87 |

111 |

116 |

Numbers over 100 indicate overall improvement. For information on how the index numbers are calculated, see the LMI Economic Index Fourth Quarter 2012 table above. |

||||

“North Dakota continues to experience low unemployment. The energy sector is still [producing] new jobs.”

—Community bank serving rural ND

“Minneapolis employment conditions are still slowly getting better, but there are still many skilled people out of work or working [in jobs that are] not suited for their skill sets.”

—Housing service provider serving urban MN

“Companies are advertising [positions] for hire. Adult skill training is offered, but in a rural community individuals may have to travel 60 miles or more to receive it, and may or may not be able to get assistance to pay for it.” —Economic development corporation serving rural SD

“Positions once open for lower-income or less-educated adults are now being filled by unemployed individuals with much higher skill levels. The availability [of] training for non-college-bound young adults is scarce.”—Community bank serving rural UP of MI

“Equipment and metal manufacturing companies have a need for more welders. Some food processing and furniture companies are hiring [immigrant workers] because [native] residents are not interested in these jobs; the wages are too low.” —Regional planning commission serving rural northwestern WI

“Recent discussions with our local job service center indicated that there is an abundance of job postings, but not a great deal of interest from job seekers. It is believed that the extension of unemployment benefits has caused job seekers to become unmotivated to seek work.”

—Community development corporation serving urban and rural MT

Housing Conditions

Foreclosure recovery, access to mortgage loans, and affordable rental opportunities

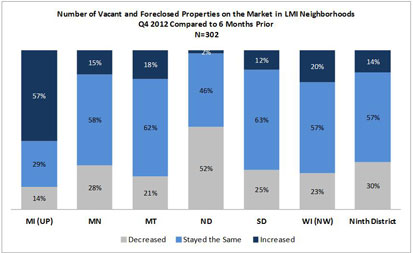

Survey responses indicate overall improvement in the number of vacant and foreclosed properties on the market in LMI neighborhoods in comparison to six months ago. Respondents credited targeted investment by local governments, effective foreclosure counseling services, and increased investor acquisition as the driving factors behind this improvement. In areas where foreclosures have increased, loss of employment, stricter lending requirements, and servicers releasing inventory for sale, were most frequently cited as the contributing factors.

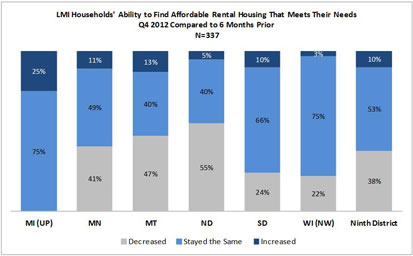

Across the District, homeownership and rental housing opportunities for LMI households continue to decline or remain unimproved. More than one-third of respondents (38%) reported a decrease in the ability of LMI households to find affordable housing that meets their needs. According to survey responses, rising rental rates and a lack of new construction to meet the growing demand for rental housing are to blame. Some housing developers also cited difficulty in obtaining the financing required to build new rental units. In North Dakota, rental housing problems continue to be exacerbated by the population influx from the oil boom.

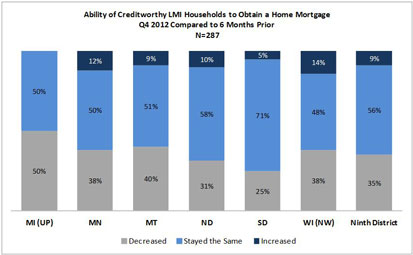

More than one-third of survey respondents (35%) also reported a decrease in the ability of creditworthy LMI households to obtain a mortgage in comparison to six months ago. Mortgage lenders across the District reported that changes in qualifying guidelines have made it more difficult for previously qualified buyers to take advantage of currently low interest rates. In some rural LMI communities, difficulty completing the appraisal process due to a lack of comparable properties has also been a barrier to lending. According to community bank respondents, overall changes in mortgage lending requirements have made it difficult for some smaller banks to continue making secondary market loans.

“A great deal of community development effort has been directed to core neighborhoods within the central cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul. The collective effort of [local government] partners coupled with community development corporation and community development financial institution activities have reduced the overall blighting effect of the subprime foreclosure crisis in these neighborhoods … Aggressive work on the part of housing and foreclosure counselors has also helped to stem the tide of foreclosures.” —Community development intermediary serving urban MN

“Our markets continue to be depressed by Fannie [Mae] and Freddie [Mac] foreclosures. They are dumping homes on the market and selling them at depressed prices. This, in turn, drives down overall values.” —Community bank serving rural UP of MI

“The increase in rent makes it more difficult for our voucher tenants to find housing. Fair Market Rates [set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development] do not go as high as the rents are increasing.” —Housing authority serving urban and rural ND

“Both the foreclosure crisis and the tightening of credit have forced many families to either enter or remain in the rental market. [In addition], no new rental housing has been built in the last six months.” —Housing authority serving urban MN

“Changes in qualifying [mortgage] guidelines have made it more difficult for even previously well-qualified borrowers to take advantage of attractive rates.” —Community bank serving rural MN

“The underwriting of mortgage loans sold to the secondary market has gone from too lenient to far too restrictive. Even for the most creditworthy borrowers, the process of obtaining a mortgage has become brutally painful in terms of the level of disclosure necessary and the amount of documentation required.” –Credit union serving urban and rural MT

“We sell secondary market loans to Freddie Mac, but their restrictive requirements are forcing us to decline many creditworthy applicants.” —Community bank serving urban and rural WI

Household Financial Well-Being

Consumer debt, use of alternative financial services, and demand for financial counseling

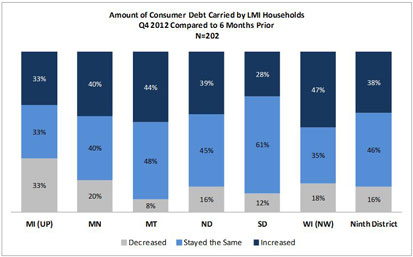

Survey responses indicate that consumer debt remains high for many LMI households, although conditions are deteriorating less rapidly than they were six months ago. Across the District, more than one-third (38%) of respondents reported an increase in the amount of consumer debt carried by LMI households, with the greatest continued increase in Montana and Wisconsin. According to survey responses, stagnant wages coupled with the rising cost of living have led many LMI households to take on additional debt in order to meet daily living expenses. For some individuals, this in turn has damaged their credit score due to their inability to make payments on the debt.

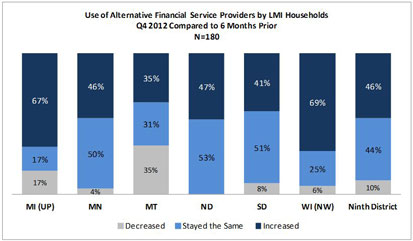

Districtwide, nearly half (46%) of survey respondents reported an increase in LMI households’ use of alternative financial service providers, i.e., payday lenders. The increase in the use of alternative financial service providers remains lower in Montana than in other parts of the District. Recently passed state laws in Montana targeted at predatory lending have drastically reduced the number of in-state payday loan operations.

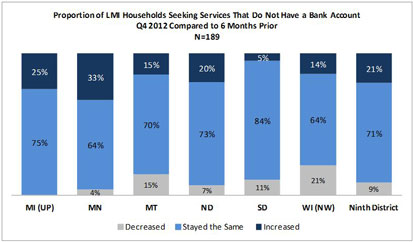

Across the District, the proportion of LMI households seeking services that do not have a bank account did not change much—although, notably, one-third (33%) of Minnesota-based respondents reported an increase in comparison to six months ago. Anecdotally, survey responses also pointed to some scattered signs of improvement, including previously unbanked households becoming members of the new credit union on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

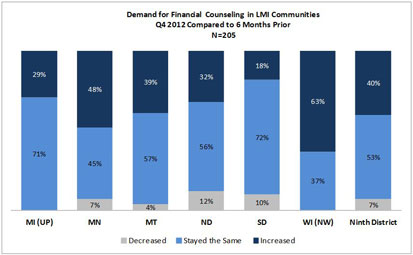

Districtwide, 40 percent of respondents reported an increase in the demand for financial counseling in LMI communities in comparison to six months ago. Though an increase in demand is frequently a sign of rising debt problems, some financial educators viewed the increase as a positive trend, since credit counseling is often an important step toward credit repair. A number of respondents in rural areas across the District indicated that, despite high demand, financial counseling was not accessible, with the nearest services often located more than 30 miles away.

“Consumer goods are becoming more expensive and incomes are not increasing, so people are turning to other sources to fill the gaps.” —Community development intermediary serving rural SD

“Consumer debt among LMI consumers continues to rise and the credit scores continue to drop due to their inability to make the payments.” —Community bank serving rural MN

“It seems that more consumers are using payday loan services to obtain loans with interest rates and payments that are so are high and the consumers’ accounts become overdrawn.” —Community bank serving urban and rural WI

“Payday lending has decreased only because Montana state law became so prohibitive that all but a few payday lenders went out of business.” —Credit union serving urban and rural MT

“Many people still do not trust the banking system and have pulled out their money. About 10 percent of the clients in our mortgage foreclosure prevention program fall into this category.” —Housing service provider serving urban and rural MN

“The first federally insured financial institution on [our] reservation opened in November 2012 … The response since we’ve opened the doors has been overwhelming. We are thrilled with the number of new members opening [bank] accounts, setting up direct deposit, [and] applying for consumer loans.” —Credit union serving rural SD

“More LMI households are looking to purchase [because of] low interest rates and low prices. [However], past credit issues need to be addressed before they can accomplish this goal.” —County community development agency serving urban and rural MN

“Courses are too long and not easy to attend while you are working. People feel that there is no incentive to take a [financial education] course unless they are forced to due to lending or other requirements.” —Community Action Agency serving rural MN

Business Activity

Credit access, business start-ups, and business closings

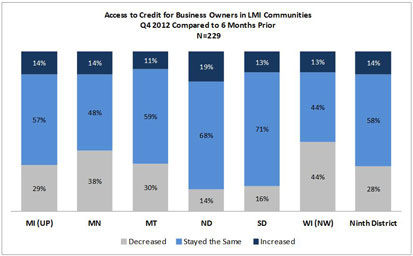

Survey results show that credit conditions for business owners in LMI communities remain unimproved in comparison to six months ago. Districtwide, more than one-quarter of respondents (28%) said that the ability of business owners to obtain the amount of credit they need has decreased. One exception is North Dakota, where business credit conditions continue to remain positive overall. (See Table 3.) Only 14 percent of North Dakota-based respondents reported a decrease in access to credit for business owners in LMI communities in the last six months. Across the District, respondents frequently mentioned that access to credit remains particularly challenging for start-ups and less established business owners. From a lender perspective, many community bankers reported that tighter regulatory requirements have prevented them from making loans.

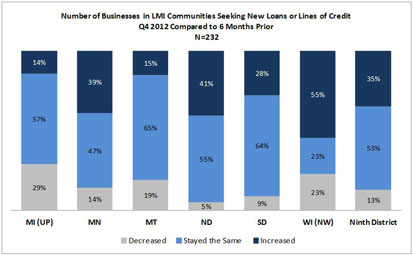

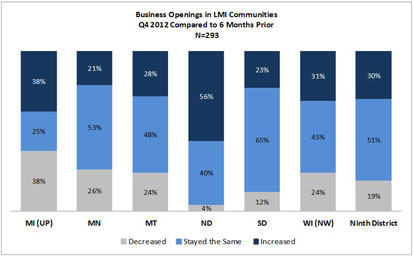

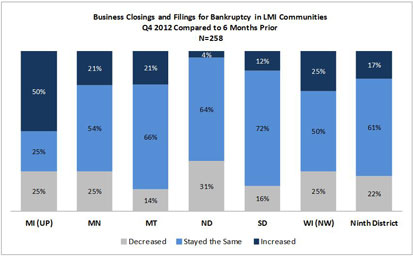

Despite unfavorable credit conditions, survey responses indicate continued increases in business activity in LMI communities. Districtwide, more than one-quarter (29%) of respondents reported an increase in the number of new businesses opening in comparison to six months ago and more than one-third (35%) reported an increase in the number of businesses seeking new loans or lines of credit. Anecdotally, lenders reported that the loan requests were for expansion or purchase of new equipment, which is a positive sign of growth.

Still, some respondents reported seeing an increase in business closings and bankruptcy filings in LMI communities in comparison to six months ago. In rural areas, respondents cited population decline and competition with online commerce as the primary reasons behind the closings. In the Twin Cities, construction of the Central Corridor light rail line has negatively impacted a number of businesses in LMI neighborhoods along the route.

| Table 3. LMI Economic Index, Q2 2011 to Q4 2012 Access to Credit for Business Owners in LMI Communities |

||||

Geographic Area |

Q2 2011 |

Q4 2011 |

Q2 2012 |

Q4 2012 |

Michigan (UP) |

25 |

14 |

120 |

85 |

Minnesota |

32 |

50 |

80 |

76 |

Montana |

31 |

69 |

76 |

81 |

North Dakota |

77 |

116 |

115 |

105 |

South Dakota |

85 |

74 |

95 |

97 |

Wisconsin (NW) |

22 |

33 |

59 |

69 |

| Ninth District | 48 |

62 |

87 |

86 |

Numbers over 100 indicate overall improvement. For information on how the index numbers are calculated, see the LMI Economic Index Fourth Quarter 2012 table above. |

||||

“More microloan assistance is needed. Equity to support small business lending remains insufficient.” —Small Business Development Center serving urban and rural WI

“Credit availability for businesses is not a problem, and competition for business loans is fierce among lenders.”

—Community bank serving rural ND

“In general, the economy is improving and we are seeing more business activity. However, small businesses are still having a hard time accessing traditional credit as loan-to-value ratios have not realigned.” —Community economic development corporation serving urban and rural MT

“Commercial businesses in eastern Montana are doing very well due to the strong economy. New businesses related to the oil industry are opening … Some local businesses have expanded or need additional credit to handle increased business volume. This is offset by businesses with reduced credit needs due to increased profitability.” —Community bank serving rural MT

“We are currently experiencing more small business loan requests for expansion and fixed asset purchases than at any time in the past four years.” —Community bank serving urban and rural MN

“I am seeing more small businesses coming to my organization for financing. It signals to me that things are starting to pick up.” —Community economic development corporation serving rural MN

“There has been an influx of businesses that are directly related to the Bakken Oil Field.” —Employment and job service provider serving rural MT

“There have been a number of business start-ups in our rural communities in the past year.” —Community bank serving rural SD

“Although we do not do direct business lending, we have seen an increase in new businesses, equipment purchases, and a limited amount of new hiring.” —Community development intermediary serving urban MN

“As the population decreases and people shop online and drive to larger communities to shop, local businesses continue to close.” —Community Action Agency serving rural MT

“Loan underwriting standards have not changed, but the financial outlook for Main Street businesses has declined. Many family-owned businesses are facing the need to close their doors for lack of profitability.” —Community bank serving rural SD

“Construction of the light rail along the Central Corridor has had [a negative impact] on LMI businesses. Access to credit has remained about the same, which is still low. Banks have not increased their business lending in many of the communities we serve.” —Community development intermediary serving urban MN

Capacity of Community Development and Service Organizations

Funding levels and the ability to meet LMI community service needs

In addition to providing insight on factors affecting the economic well-being of households and businesses in the community, we asked respondents to share their perspectives on their own organization’s financial outlook and ability to meet ongoing community service needs.

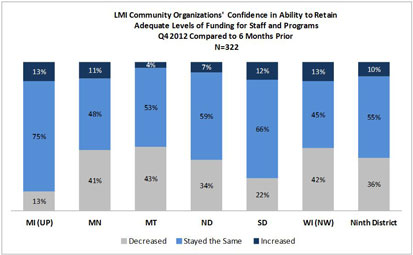

Survey respondents continued to report declining confidence in their ability to retain adequate funding for staff and programs. Districtwide, more than one-third of respondents (37%) reported a decrease in comparison to six months ago. However, conditions are deteriorating less rapidly than in June 2011 when tracking of this indicator first began. (See Table 4.) Respondents frequently expressed concern about the uncertainty of government funding sources and also increasing operational costs. In addition to a lack of adequate funding for paid staff, some respondents mentioned increased difficulty with volunteer recruitment and retention. Reasons included both poor economic conditions and an aging population, particularly in rural areas.

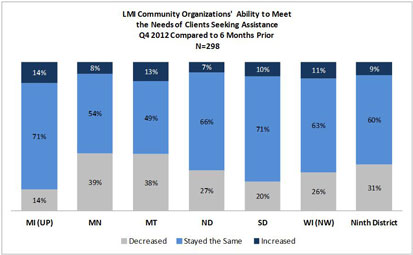

Districtwide, LMI community organizations’ ability to meet the needs of clients seeking assistance has either declined or remains unimproved. Almost one-third of respondents (31%) reported a decrease in their ability to meet the needs of clients seeking services in comparison to six months ago. This sentiment was true not only among providers of services to LMI households, but also among those providing services to business owners in LMI communities, including technical assistance and loans. For many, the increased demand for services coupled with decreased funding and/or the rising cost of doing business has made service delivery extremely challenging.

According to survey responses, some middle-class households continue to struggle with making ends meet post-recession. Forty-three percent of respondents reported an increase in the number of “formerly middle-class” households seeking assistance from LMI community organizations in comparison to six months ago. While North Dakota and South Dakota appear to be faring better than other states, the fact that this indicator continues to show little or no improvement across the District remains a cause for concern.

| Table 4. LMI Economic Index, Q2 2011 to Q4 2012 Confidence in Ability to Retain Adequate Levels of Funding for Staff and Programs |

||||

Geographic Area |

Q2 2011 |

Q4 2011 |

Q2 2012 |

Q4 2012 |

Michigan (UP) |

75 |

36 |

100 |

100 |

Minnesota |

47 |

63 |

77 |

70 |

Montana |

43 |

75 |

72 |

61 |

North Dakota |

42 |

63 |

77 |

73 |

South Dakota |

74 |

83 |

83 |

90 |

Wisconsin (NW) |

31 |

43 |

68 |

71 |

| Ninth District | 50 |

66 |

75 |

74 |

Numbers over 100 indicate overall improvement. For information on how the index numbers are calculated, see the LMI Economic Index Fourth Quarter 2012 table above. |

||||

“There is a great deal of concern in the nonprofit community about the ‘fiscal cliff’ and [the] potential for severe reductions in funding for our programs and operations. Nonprofits appear to be working together more and finding ways to leverage resources. With limited resources available, there have been some mergers and exploration of more in-depth partnerships.” —Community development intermediary serving rural MN

“Our agency is closing due to the reduction in funding and the [increased cost of] IT, auditing, and reporting requirements. We merged with another Community Action Agency to save on overhead and program costs.”

—Community Action Agency serving rural MN

“Funding for community resources is lower. We are seeking to increase collaboration to meet the demand for resources. There continues to be a strong demand for start-up and expansion assistance.” —Small Business Development Center serving urban and rural WI

“LMI household budgets are stressed by inflation of daily living expenses. This has had a direct impact on community organizations’ ability to recruit volunteers, as younger individuals do not have the time to volunteer and older people are no longer physically or financially able to participate.” —Community bank serving rural ND

“We are hearing from many of our funded agencies that they continue to see increasing numbers of middle-class (or formerly middle-class) people seeking assistance and services. This seems to be most prevalent at food shelves.” —Foundation serving urban MN

“Funding cuts have resulted in our need to cut personnel, which [negatively] affects service delivery. There are more people who were middle-class and now are laid off or without work, who are seeking services.” —Housing service provider serving urban MN

Note

* Unemployment benefits are calculated based on employment rates and state unemployment insurance laws. As of March 2013, maximum unemployment compensation in Ninth District states ranged from 40 to 54 weeks. For more information on the number of weeks of unemployment compensation available by state, see the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

About Ninth District Insight

The Ninth District Insight Survey is designed to capture front-line observations about issues that affect the economic health of LMI communities. Participants’ responses serve as leading indicators of change in conditions that are otherwise difficult to measure or are not measured through other existing data sources. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis senior leadership and Community Development staff use Ninth District Insight to help identify regulatory and policy issues that deserve attention and to decide how Community Development program resources should be targeted. We hope that the community-based perspective that Ninth District Insight provides also serves as a valuable resource for decision makers outside the Federal Reserve System.

Participation in Ninth District Insight is entirely voluntary and no individually identifiable information is reported. If you would like your organization to be considered for inclusion in the next survey, contact Ela Rausch at ela.rausch@mpls.frb.org.