Video: fedgazette Writer Phil Davies on labor's changing face

The Quick Take: Congressional efforts to overhaul the U.S. immigration system have thrown a spotlight on the foreign-born, whose contribution to the Ninth District workforce has increased in recent years. Recent immigrants—those who entered the United States within the past five years—come predominantly from Asia, Latin America and Africa as legal immigrants, temporary “guest workers” and unauthorized workers who cross U.S. borders or overstay their visas.

Many new immigrants hold lower-paying jobs in the production and service sectors. But highly educated foreign workers, including guest workers on H-1B visas, cluster in well-paying occupations such as information technology and health care.

Labor demand, together with other factors, has fostered concentrations of foreign workers in many district communities, such as the Twin Cities, St. Cloud, Minn., and Sioux Falls, S.D. An aging native-born labor force means that foreign workers are likely to play a more important role in the district economy in the future.

When Dakota Provisions opened for business in 2005, acquiring over 400,000 live turkeys a month to process into cold cuts, ground turkey and other products was easy. Hiring enough workers to staff the $120 million plant in Huron, S.D., was harder. In a city of 11,500 people surrounded by corn and soybean fields, not enough locals were willing to man the production lines, at least for the going wage at the plant.

“We started out trying to employ a local workforce,” said Mark “Smoky” Heuston, human resources director for the plant. “Six months to a year after, because we were growing, we had to go out and find workers from other areas.”

The plant recruited Latino workers who came to the Huron area from southern states and other countries such as Mexico and Guatemala. But interviewing Latino workers was time-consuming and frustrating because many proved ineligible to work in the United States; they were illegal immigrants. So Heuston turned to another source of foreign-born labor: Karen refugees from Myanmar.

In recent years, many Karen, an oppressed ethnic group in the Southeast Asian country (formerly Burma) have been admitted to the United States as refugees. Heuston went to St. Paul, Minn., to recruit Hmong—another ethnic group from Southeast Asia—and met some Karen in an English language class for refugees. He offered jobs to a family and a single man—the start of a major Karen migration to Huron from St. Paul, Green Bay, Wis., Lincoln, Neb., and other communities around the country. “They came here just as fast as we could possibly hire them,” Heuston said.

Today more than two-thirds of the production workforce at Dakota Provisions is Karen, and about 170 Karen families have settled in the area, spurring new housing construction.

Efforts to overhaul the U.S. immigration system have thrown a spotlight on foreign-born labor. Most of the debate in Washington has focused on illegal immigration—how to secure the Mexican border and whether to provide a “path to citizenship” for undocumented workers. But proposed changes in immigration law would also affect a large number of foreigners authorized to work in this country, particularly recently arrived immigrants. For example, loosening restrictions on work visas may increase inflows of H-1B visa holders—highly skilled temporary workers coveted by many employers in scientific and technical fields.

The immigrant workforce in the Ninth District has increased in recent years, outpacing growth in the overall workforce, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Industries in which foreign workers are in high demand include food processing, agriculture, information technology and health care. Demand is especially acute in rural areas with low unemployment or that are off the beaten path for doctors and other sought-after professionals.

Labor demand combined with migration patterns has fostered concentrations of foreign workers in many district communities—clusters of immigrants from certain countries or regions of the world that grow as new immigrants arrive seeking opportunity. The strong presence of immigrants in these markets stems partly from the reluctance of U.S.-born workers to take jobs in industries such as farming and meat packing at the prevailing wage.

This article offers a portrait of immigrant workers in the district, with a focus on new immigrants—where they come from, how they enter the workforce and why certain industries have come to depend upon their foreign labor.

Immigrant labor on the rise

The contribution of immigrants to the American workforce and economy goes back to the nation’s founding. Early immigrants from Britain worked on farms and in households as indentured servants. In the mid-19th century, Germans and Scandinavians crossed the Atlantic to claim Midwestern farmland, while Irish fleeing the potato famine settled mostly in urban areas. The late 1800s and early 20th century saw successive waves of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe who provided the muscle for burgeoning industry. More recently, in the 1960s, landmark immigration legislation opened the United States to workers from Latin America, Asia and Africa.

Today about one in six U.S. workers was born in another country. District states—far from traditional immigrant gateways on the coasts and along the Mexican border—are home to comparatively fewer foreign workers. In 2011, the foreign share of the workforce in the district ranged from a high of 9 percent in Minnesota to just 2.5 percent in Montana, according to Census estimates based on household surveys.

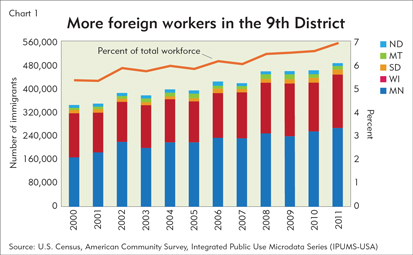

But as Chart 1 shows, the ranks of the immigrant workforce are swelling in the district. From 2005 to 2011, the number of foreign-born either employed or looking for work in district states increased about 4 percent annually—a growth rate more than four times that of the total workforce. (However, there was considerable variation among states; South Dakota’s immigrant workforce grew by more than half over this period, while Montana’s fell by about 20 percent.) Thanks to this growth, in 2011 the foreign share of the district workforce was higher than at any point in the past 60 years.

Growth of the immigrant workforce has been much greater in the district than in the country as a whole—a trend driven partly by the strength of district state economies relative to the rest of the country. In Minnesota, the district state with the largest immigrant population, the nonnative workforce declined during the Great Recession. But it has rebounded during the recovery, gaining 28,000 workers from 2009 to 2011.

Minnesota State Demographer Susan Brower attributes the resurgence in her state to a lower-than-average unemployment rate and a high concentration of jobs in information technology, health care and other industries that employ foreign workers.

The newcomers

A fedgazette analysis of individual Census records found that in 2011, about 20 percent of the foreign-born workforce in district states had come to the United States within the past five years. Since 2005, this ratio has risen as high as 30 percent—evidence of a constant infusion of newcomers into the nonnative population. Moreover, the Census data show that a large share of these new immigrants had moved to the district even more recently; in 2011, roughly half reported that they were living in a state outside the district or in another country the previous year. (The number of foreign residents leaving the region or the United States each year is unknown.)

New immigrants are less likely to be acclimated to life in America than the overall foreign-born population—unfamiliar with the culture, not fluent in English, possessing skills imperfectly matched to the job market. Because many recent arrivals are neither U.S. citizens nor permanent residents (“green card” holders permitted to work in the U.S. indefinitely), they would be affected the most by changes in immigration laws.

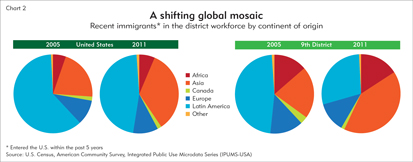

Most of these recent arrivals come from Latin America, Asia and Africa, but over 100 countries from every corner of the globe export labor to the region. The origin of recent immigrants in the district workforce skews differently from that of the nation, with fewer Latinos and more Asians and Africans. And both nationally and in the district, the sources of new foreign labor have changed over the past half-decade (see Chart 2).

From 2005 to 2011, the share of Latinos among recent arrivals shrank, while the proportion of Asians expanded. This pattern held in every district state except South Dakota, where the share of people from Mexico and Central America increased. Brower noted that migration from Mexico has fallen due to the U.S. recession and improved economic conditions south of the border. “The Mexican economy has picked up, and there are more job opportunities there than in the past,” she said. “Overall, the supply of Mexican immigrants has diminished in the U.S., and we’re seeing some of the effects of that here in Minnesota.”

Meanwhile, many states in the district and across the country have seen an influx of refugees, high-skilled temporary workers and university students from Asian countries such as China, India, South Korea and Myanmar. Between 2006 and last year, Asian enrollment in the North Dakota University System more than tripled to almost 900 students, according to system records.

Ready to work

The foreign-born move to areas where they can find jobs suited to their work experience and abilities. They also pull up stakes to join relatives, friends or an established expatriate community, but employment often determines whether they stay in a community or move on.

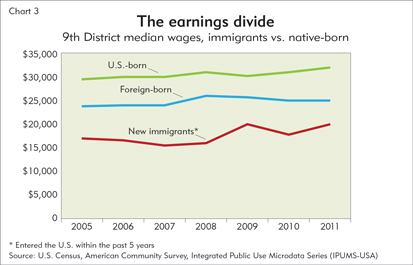

As a group, immigrants receive lower wages than U.S.-born workers; in 2011, the median wage for foreign workers in district states was about 75 percent of the wage for the native-born (see Chart 3). New immigrants earn much less than either the native-born or immigrant workers overall—as one might expect, given that most recent arrivals haven’t mastered English or amassed much work experience.

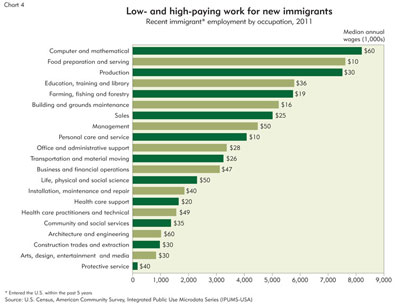

Recent arrivals cluster in industries such as manufacturing, food preparation, farming, personal care and building maintenance (Chart 4). Many occupations in these industries—meat processing and nursing assistance, for example—pay annual wages under $31,000, the median for all district workers in 2011.

But a subset of new immigrants—almost one-quarter of the total—is concentrated in occupational groups such as computing, the sciences and higher education that pay median annual wages of at least $50,000. (These high earnings elevate the average pay of all new immigrants.) Census data show that in Minnesota, over 3,700 newly arrived foreigners held computer and mathematics jobs in 2011; of those, about 80 percent were born in India—part of a wave of migration by highly educated Indians to places like the Twin Cities suburbs and Rochester over the past decade.

In the district and across the nation, employers hire foreign workers because they cannot—or choose not to—fill positions with homegrown labor. In a recovering economy, employers face tight labor markets in some areas, such as Sioux Falls, S.D., a booming agricultural, financial and health care center where the unemployment rate was 3 percent in August. “The difficulty for everyone is, when unemployment gets that low, the pool of very productive, reliable and skilled employees becomes smaller and smaller,” said Kent Alberty, co-owner of Employment Edge, a local staffing firm.

Native-born workers with highly desired skills—doctors, engineers, web developers—may be particularly scarce. Foreign workers provide an acceptable, sometimes preferable, substitute.

But for the most part, employers turn to foreign workers—particularly new arrivals—as a source of inexpensive labor. In many district communities, new immigrants may be the only workers around who will take certain types of production and service jobs at the wages offered (see related article for more on the impact of immigrants on the labor market and the economy).

Several distinct streams of U.S. migrants come together to form the immigrant labor pool. Hiring some types of foreign workers is often a simple matter of phoning a refugee resettlement agency or placing a newspaper ad. Acquiring others, such as H-1Bs and other classes of guest workers, can be much more difficult, involving fees and paperwork to comply with regulations that have tightened in recent years.

From oppression to opportunity

Over the past decade, tens of thousands of refugees from global strife have settled in district states—one reason that proportionately more Asians and Africans live in the district than in the nation overall. Refugees from countries such as Somalia, Eritrea, Sudan, Iraq, Myanmar and Bhutan contribute to a larger share of migrants from those continents.

Minnesota leads the district (see Chart 5) and is among the top U.S. states on a per capita basis in accepting refugees, immigrants permitted to live and work in the country permanently.

In most district states (Montana, with virtually no refugee resettlement, is the exception), social welfare organizations such as Lutheran Social Services (LSS) help refugees learn English, find housing and land jobs. Minnesota has additional organizations playing a large role, including Catholic Charities and the International Institute of Minnesota in the Twin Cities, which sponsored 383 refugees in 2012 and 400 through September of this year.

In addition to refugees who come directly to the district from their home countries, some district states also attract significant numbers of secondary migrants—refugees who move from elsewhere in the country, either to join family members or to find work. That’s how the Somali community in Minnesota has grown from a small core in the 1990s to become the largest in the country, notes Kim Dettmer, who oversees refugee settlement in the St. Cloud area for LSS. “Refugees may have resettled in Texas or another state, but they really want to live in Minnesota.”

Either because they lack the requisite skills or speak poor English, most refugees fill relatively low-paying jobs in industries such as food processing, light manufacturing and health care support. Resettlement agencies, which receive federal funding to assist refugees, provide pre-employment counseling and training. LSS’s Immigration and Refugee Office in Sioux Falls works with local employers to prepare refugees for entry-level production positions. “Refugees are entering positions that right now are not being filled [by U.S.-born workers], and we’ve had great success with that,” said Director Tim Jurgens.

Refugees make up much of the workforce at meat-packing plants in Sioux Falls, St. Cloud and other district communities.

Dakota Provisions readily hires refugees settled by LSS and secondary migrants who move to Huron from elsewhere in the country. Heuston said the Karen are industrious workers who learn readily on the job and turn up every day (turnover has fallen as the proportion of refugees on the payroll has risen). Line workers earn about $12 per hour—a competitive wage in meat packing, but not enough to induce U.S.-born workers to take jobs processing turkey meat, he said.

Hospitals, nursing homes and other health care facilities also have come to rely upon refugees to feed, bathe and provide other personal care to the sick and elderly, often for low pay. At some long-term care facilities in the Twin Cities, 80 percent of the staff are refugees who have taken nursing assistant training offered by the International Institute, said Amanda Smith, refugee services director for the organization.

Census data indicate that most immigrant workers in health care facilities come from African nations such as Ethiopia, Somalia and Liberia; in Minnesota in 2011, Africans accounted for about three-quarters of recently arrived immigrants working as nursing assistants and in other entry-level health care jobs.

Give me your doctors and engineers ...

At the other end of the wage spectrum are H-1B visa holders, highly educated and skilled workers who labor in office towers, hospitals and universities. H-1Bs are one class of guest workers permitted to work temporarily in the United States under federal programs meant to help firms adapt to changing economic conditions (see accompanying article for a description of various types of work visas).

Workers with H-1Bs typically hold well-paying jobs in fields requiring specialized knowledge, such as information technology, health care, finance and academia. In 2011, the average annual salary of an H-1B worker in Minnesota was over $65,000, according to the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL).

Nationwide, demand for H-1B guest visas exceeds supply, because of a statutory cap of 65,000 on the number of new visas issued annually. Employer requests for H-1Bs have exceeded the number issued every year over the past decade, and this year’s quota was filled in less than a week after filings began in April. There are no data on work visa issuances by state, but a look at visa applications in the district indicates that employer demand for H-1Bs is high in the region—and probably not being met.

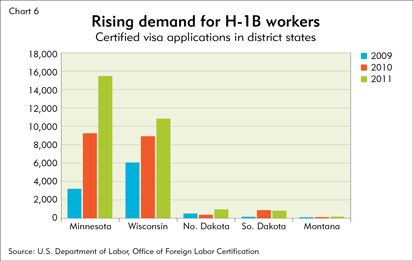

The DOL’s Office of Foreign Labor Certification must approve employer requests for H-1Bs. Figures compiled by the DOL show a sharp increase in H-1B certifications in district states from 2009, when the recession ended, to 2011 (see Chart 6).

Certifications were concentrated in Minnesota and Wisconsin, and in district cities with large universities and thriving computer and health care industries. In 2011, Twin Cities employers accounted for over 8,000 certifications, and there were over 650 in the Fargo area, home to a Microsoft campus and Sanford Health, the largest rural nonprofit health care system in the country.

But the number of H-1Bs ultimately issued by the U.S. State Department is significantly smaller; nationwide in 2011, there were six times as many visa certifications as issued visas. It’s not known whether rates are higher or lower in district states.

District hirers of H-1Bs say they provide critical expertise—knowledge and abilities not always available in the domestic workforce—that helps them to develop new products and services or expand their operations.

At Microsoft’s complex in Fargo, hundreds of H-1B visa holders work in product R&D, tech support and internal computer systems. The majority come from India, Pakistan, China and Eastern Europe. Campus head Don Morton says that smart, highly capable workers from overseas are needed to keep the software giant competitive in a borderless market.

“We compete globally for customers ... and we compete globally for talent,” he said. “Regardless of whether a person is foreign-born or native-born, we’re going to try to hire the very best talent available.” Like many high-tech executives, Morton believes that not enough talented U.S.-born college students are pursuing science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) degrees.

In the health care industry, foreign-born physicians on H-1B visas fill job openings in rural areas of the district. Hospitals and clinics operating in northern Minnesota and much of North Dakota say they struggle to hire enough U.S.-born doctors, especially specialists in less popular medical fields or those willing to provide primary care in small towns.

“The biggest challenge is giving a sales pitch to a physician to come and practice medicine in a rural western Minnesota community of a thousand or two thousand,” said Dr. Richard Marsden, senior executive vice president of Sanford Health’s outpatient services in Fargo.

By hiring H-1Bs, Sanford can skip the sales pitch in most cases. The company has hired scores of foreign physicians and last summer employed over 80 H-1B doctors, including specialists in family medicine, cancer treatment, pediatrics and critical care. Most of them came to Sanford right out of a U.S. medical school and are required to work in underserved areas for at least three years as a condition of receiving their H-1Bs. As a research institution, Sanford is exempt from the annual nationwide cap on H-1B visas.

Securing the services of H-1B workers is a time-consuming and expensive proposition for employers. The application process can take up to six months, and immigration authorities charge fees of $2,300 to $3,500 per worker. Such fees, including a payment that helps to fund job training for U.S-born workers, have risen over the past five years. Then there are typical attorney’s fees of over $1,500 for each worker—which the employer pays regardless of whether their visa application is successful. This year, because the national H-1B visa cap was exceeded, a lottery was held to determine winners and losers.

Despite the overall increase in H-1B applications, “a lot of employers are forgoing the program, because it’s become so expensive,” said Sam Myers, an immigration attorney with the Myers Thompson law firm in Minneapolis.

... and I’ll take your waiters and farm laborers too

In addition to the H-1B program, there are work visa programs geared to low- and semi-skilled workers—the H-2A visa for agricultural workers and the H-2B for nonfarm workers. These programs are seasonal as well as temporary; most lower-skilled guest workers in the district return to their home countries at the end of the summer or after the fall harvest.

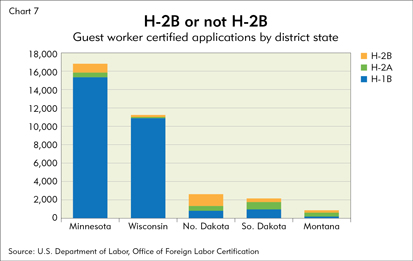

In district states, the DOL certifies far fewer H-2A and H-2B applications than H-1B requests, but in Montana and the Dakotas the lower-wage visas account for a greater proportion of total guest worker certifications (see Chart 7).

The energy boom in western North Dakota and eastern Montana has spurred demand for guest workers to fill positions in construction, food processing, hospitality and other industries—not just in the oil patch but also in surrounding areas that have seen an exodus of workers seeking higher wages in the oilfields.

Employment USA, a guest worker recruiting agency in Aberdeen, S.D., has capitalized on that demand. The firm lost business nationwide during the recession, but since 2010, revenues have increased over 40 percent annually on the strength of placements in the Dakotas. Employers unable to compete with high wages in oil-producing areas have turned to foreign temporary workers to fill out payrolls, said owner Kevin Opp.

“The oil boom is affecting the job market in the entire region. ... People can go [to the oil patch] and without a ton of experience make $75,000 to $80,000 a year working just as hard as if they had a cement construction job here in Aberdeen.”

About 1,000 workers recruited by Employment USA from Mexico, Canada, South Africa and several nations in the Caribbean and Eastern Europe work in the Dakotas on either the H-2A or H-2B program. Typical jobs include farm labor, basic construction, meat processing and waiting tables—“pretty simple work that doesn’t take a lot of experience,” Opp said.

The allure of oil country has further strained labor supplies in the Black Hills of South Dakota, where demand for workers in hotels, restaurants, resorts, amusement parks and other businesses peaks during the summer tourist season.

The Powder House Lodge and Resort near Keystone, S.D., hired its first H-2B workers through Employment USA in 2005. Ben Brink, one of the owners of the small, family-run resort, said hiring workers each summer was difficult because of the area’s low unemployment and small pool of high school seniors and college students.

“We were just having staffing problems, and [hiring foreign workers] was a solution that was readily available to us,” he said. “It has honestly saved our business.” The resort hires 16 to 17 H-2B workers each season—about one-third of its full-time staff—to cook, serve food, clean rooms, maintain the grounds and staff the front desk. Most of the workers live onsite for the summer, paying $7.50 a day for accommodations.

Companies that hire lower-wage guest workers—H-2Bs in South Dakota earned about $8.50 per hour in 2011, according to the DOL—don’t face the same supply constraints as those using the H-1B program. There is no national cap for H-2A visas, and since 2008, H-2B issuances have not exceeded the statutory cap.

But as is the case for the H-1B program, hiring foreign workers through these programs can tax employers’ patience and pocketbooks. In addition to paying filing fees and commissions to recruiting agencies, firms often have to arrange for or provide housing for workers. And in 2009, the DOL began requiring H-2B employers to pay workers’ transportation expenses from their home countries—adding hundreds of dollars in airfare to the cost of hiring workers from overseas.

Government red tape has at times disrupted the flow of guest workers. Earlier this year, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services suspended processing of H-2B petitions because of a court challenge to the method used by the DOL to determine the prevailing wage to be paid to workers. Opp said the month-long suspension came during the critical sign-up period for the summer season, reducing the number of H-2B workers available to employers.

Got cows to milk?

A large proportion of foreign workers who have come to district states in recent years are neither refugees nor guest workers. Many are legal immigrants or permanent residents admitted because they’re relatives of U.S. citizens or permanent residents. The federal government grants a much smaller number permanent residency (making them eligible for U.S. citizenship) because they possess coveted expertise or work skills. And some are undocumented workers (see sidebar) from Mexico and other countries.

Just how many new foreign workers in each category are in the district labor force at any given time is unknown; their movements and employment status are not tracked by any government agency. But there’s anecdotal evidence that they contribute in important ways to the labor supply of the region.

Responding to unrelenting demand for labor in western North Dakota, foreign workers from all over the country have come to the region in recent years, seeking jobs in oil drilling, construction, food service and other industries. “We’re seeing a large pool of folks across the board [migrate to the area], including the foreign-born,” said Richard Rathge, the former state demographer for North Dakota.

Phil Davis, who heads North Dakota Job Service operations in the western half of the state, said the Bismarck and Williston offices are “seeing more foreign workers show up” and handling an increasing volume of telephone calls from Mexicans looking for work.

In Minnesota and in South Dakota, foreign-born Latinos who have migrated north from southern states such as Texas and Arizona work alongside refugees and the native-born in meat-packing plants. Last summer, Dakota Provisions employed about 50 workers born in Mexico and other Latin American countries, in addition to roughly double that number from the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico.

And dairy farmers in the Dakotas depend upon workers from Mexico and Central America to staff large operations with hundreds of cows. “Our dairy farm families are trying to hire locally, but nobody wants to work on a dairy farm,” said Roger Scheibe, executive director of South Dakota Dairy Producers. “So what they end up doing is hiring immigrant workers, usually Latinos.”

Scheibe estimates that 60 percent of the milk produced in the state comes from cows milked by foreign-born workers.

Foreign, and here to stay

The “melting pot”—the process of assimilation into the economic and cultural mainstream—is a great American tradition. Over time, as recent immigrants learn English and acquire new skills either in the classroom or on the job, their economic fortunes rise, and they stand out less from the background of the overall workforce.

This melding is evident in the Census and wage data: Compared with recently arrived immigrants, the overall foreign workforce is less concentrated in lower-paying occupations such as food preparation, farm labor and building maintenance. Consequently, as Chart 3 shows, the median wage of all foreign workers hews closer to that of U.S.-born workers. In addition, immigrants who have lived in the United States at least five years are more likely to be employed.

Vocational training programs can put the foreign-born on the path to upward mobility. English, math and anatomy classes offered through the International Institute of Minnesota prepare refugees and other immigrants to pursue college degrees in nursing. Many students are nursing assistants who want to advance their health care careers and earn higher pay, said Amanda Smith, the refugee services director. “Since the college readiness program began in 2000, we’ve helped over 350 people become registered nurses, LPNs (licensed practical nurses) and other medical professionals.”

Holders of H-1B visas who become permanent residents can switch employers and seek opportunities in other industries. At Altru Health System, based in Grand Forks, N.D., most of the H-1B physicians hired over the past three years have applied for green cards, said Joel Rotvold, executive physician recruiter for Altru.

Other foreign workers start businesses and become employers themselves; in Huron, a Karen refugee family has opened a grocery store. In 2010, the share of U.S. immigrants who started businesses was more than twice the entrepreneurship rate for the native-born, according to a report by the Small Business Administration.

The growth trajectory of foreign labor in the district depends in part on how immigration reform pans out. Changes to immigration laws could quicken the inflow of some types of foreign workers while increasing the workforce participation of those already here. For example, in addition to raising the annual cap for new H-1B visas, the Senate immigration bill would make it easier for current H-1B workers to change employers and remove limits on green cards for foreigners who earn advanced STEM degrees at U.S. universities.

As for unauthorized workers, tougher border security may reduce the number of people who cross the Mexican border illegally and make their way north to the district. But granting unauthorized workers provisional legal status could increase the number who settle permanently and hold full-time jobs. “If those people that are somehow flying under the radar had a pathway to become legal, then they wouldn’t have to hide from us,” said Kent Alberty of Employment Edge.

Regardless of the outcome of Congress’ deliberations on immigration, foreign workers appear destined to play a more important role in the district economy, because an aging population is reducing the pool of available labor. Immigrant workers, who on average are younger than U.S.-born workers, are well positioned to fill vacant positions during the economic recovery and for years to come.

“We expect that as our population ages in Minnesota, our labor force will grow at a slower rate than it has in past decades,” Minnesota State Demographer Susan Brower said. “Most states are in the same boat as us with respect to aging. This means that we may need to continue to look to labor markets outside the U.S. for our workers.”

Research Assistant Bijie Ren contributed to this article.