I. Introduction

Supervisors use a variety of data as inputs to assess the condition of banks.1 This essay focuses on supervisory use of market data, primarily prices from financial markets.2, 3 In particular, we review a specific Federal Reserve proposal that would more formally use certain types of market data (“market data thresholds”) to identify large banks requiring additional supervisory scrutiny.4

We examine the proposal in Section II by describing a system of market data thresholds. In Section III, we examine how the thresholds performed prior to and during the recent financial crisis. In Section IV, we compare this performance relative to select supervisory assessments. We conclude that market data, utilized in this fashion, would augment other information incorporated in supervisory assessments.

We examine the proposal in Section II by describing a system of market data thresholds. In Section III, we examine how the thresholds performed prior to and during the recent financial crisis. In Section IV, we compare this performance relative to select supervisory assessments. We conclude that market data, utilized in this fashion, would augment other information incorporated in supervisory assessments.

Market data do not offer a free lunch, however. Section V notes the challenges supervisors face in using market data. We discuss a research agenda to help address those challenges in Section VI. We conclude in Section VII.

II. Market Data Thresholds

Why do supervisors review market data in the first place? After all, bank supervisors have access to information about banks that investors do not. And markets may strike at least some observers as subject to bubbles and other phenomena that cast their assessments of firms in doubt. (We discuss additional limitations of market data in Section V.)

In concept, market data also have many attractive features that have led supervisors to review them when assessing the condition of banks:

- Market investors who buy and sell securities related to banks have money at stake. Investors therefore have an incentive to gauge the risks posed by banks, particularly the risk that a weakened bank will generate losses for investors.

- Markets aggregate the multitude of participants’ risk assessments into a single measure, such as the price or quantity traded of a security, which can be compared across many firms.

- Banks and supervisors do not set market prices, making prices an independent source of information.

- Market measures are often available on a frequent basis (daily or even by the minute in some cases).

- These measures can be continuously updated to reflect new information as it becomes available.

- Financial market prices are forward-looking. Market measures reflect expected outcomes based on today’s available information; accounting and financial data on the condition of banks often reflect past experience.

Potentially, then, market signals are a cheap, insightful and objective measure of bank risk-taking.

The question is, how do the market data perform in practice as an input to supervision?

We answer this question in a narrow way. We examine a particular type of supervisory use of market data: market data thresholds. Under this approach, supervisors would give additional scrutiny to bank holding companies with assets greater than $50 billion (“large banks”) that breach the thresholds. This approach—which builds on current use of market data in supervision—is embodied in a Federal Reserve proposal implementing one aspect of the very broad Dodd-Frank Act. Box 1 summarizes this proposal and the relevant parts of the DFA that prompted it. Appendix 1 discusses the evolution of supervisory use of market data.

Box 1

Summary of the Federal Reserve’s Proposal on Market Data Thresholds in the Dodd-Frank “Early Remediation” Regime

Section 166 of the Dodd-Frank Act (DFA) requires the Board of Governors, consulting with other agencies, to “prescribe regulations establishing requirements to provide for the early remediation of financial distress” of large banks and nonbank financial firms deemed systemically important.

According to the DFA:

The purpose of the early remediation requirements under subsection (a) shall be to establish a series of specific remedial actions to be taken by a nonbank financial company supervised by the Board of Governors or a bank holding company described in section 165(a) that is experiencing increasing financial distress, in order to minimize the probability that the company will become insolvent and the potential harm of such insolvency to the financial stability of the United States.a

The DFA requires the early remediation regime to define measures of a large bank’s financial condition, to link supervisory responses or limitations to the measures of the condition and to have those requirements become more stringent as the condition of the large bank weakens. The act gives the Federal Reserve some discretion in defining the measures of the financial condition and the appropriate response. But, and notably for our discussion, the DFA requires the use of forward-looking measures of the condition, which made market signals a good candidate for early remediation.b

A Federal Reserve proposal for incorporating market data into an early remediation regime required by section 166 of the DFA builds on the post-crisis use of market data.c The Board of Governors included market data in the proposal, thinking that such prices complement supervisory information and could provide “an early signal of deterioration in a company’s financial condition.” Specifically, the proposal sets out several “thresholds” based on market prices. The thresholds would identify firms whose relevant market prices are worse than pre-specified levels. The proposal describes several potential thresholds: market signals that suggest a chance of default higher than a peer group, higher than is normal for that firm or higher than a preset tripwire. A firm whose market prices breach a threshold face heightened supervisory review (so-called level 1 remediation in the proposal). Specifically, the Board of Governors would produce a report within 30 days of a threshold breach, essentially assessing the condition of the firm and determining if additional remediation makes sense. The proposal effectively formalizes current practice.

The proposed use of market data in the early remediation regime received several comments from outside parties. Several of the comments were generally supportive, with representatives of the banking industry expressing concern.d

To be clear, the market data thresholds are only one part of the early remediation regime. The majority of thresholds in the early remediation regime are not market based. The four others concern risk-based capital/leverage, stress tests, enhanced risk management and risk committee standards, and enhanced liquidity risk management standards.

There are also different types of remediation in response to a threshold breach under the early remediation proposal. They are the already mentioned heightened supervisory review (which applies to the market data threshold), initial remediation, recovery and recommended resolution. To provide some context, the third level of remediation, for example, requires that the Federal Reserve place a firm under a written agreement that prohibits all capital distributions, any quarterly growth of total assets or risk-weighted assets and material acquisitions, among other steps.

a See Section 166 (a) and (b) of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reformand Consumer Protection Act (Public Law 111-203, July 21, 2010).

b The DFA notes that early remediation should have “measures of the financial condition of the company, including regulatory capital, liquidity measures, and other forward-looking indicators.”

c The proposal can be found here.

d One of the most detailed and supportive comments came from Moody’s Analytics [pdf]. Comments by Sheila Bair and others and the Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee were also generally supportive. For concerns about the proposal, see the April 27, 2012, comment from The Clearing House and others. To review the comments on the proposal, see this.

We back-test a system of market data thresholds along the lines of those recently proposed by the Federal Reserve. Appendix 2 describes the market data thresholds we review in detail. We summarize the key features at a very high level here:

We use five types of market signals (e.g., credit default swaps (CDS)) to construct the thresholds. We develop six thresholds for each of the five signals. One relates to the absolute level of the signal, the second relates to the difference between the signal and a group of low-risk peers and the last four relate to changes in the signals.

We review these signals for 33 firms (listed in Box 2):

- 10 financial organizations that required private or public resolution in the face of failure during the financial crisis (“resolved financial organizations”)5 and

- 23 large banks that were above $50 billion as of December 2004 or December 2011, were not controlled by a foreign banking organization and were not resolved privately or publicly (“nonresolved large banks”).

Box 2

The 23 Large Banks That Were Not Resolved:

- American Express Keycorp

- Bank of AmericaM&T Bank Corp.

- Bank of New York Mellon MetLife

- BB&T Corp. Morgan Stanley

- Capital One Financial Northern Trust

- Citigroup PNC Financial Services

- Comerica Inc. Regions Financial

- Fifth Third Bancorp State Street

- Goldman Sachs Suntrust Banks

- Huntington Bancshares U.S. Bancorp

- JPMorgan Chase Wells Fargo

- Zions Bancorporation

The 10 Financial Organizations That Required Public Or Private Resolution:*

- American International Group

- Bear Stearns

- Countrywide Financial

- Fannie Mae

- Freddie Mac

- Lehman Brothers

- Merrill Lynch

- National City Corp.

- Wachovia Bank

- Washington Mutual

* We restrict this list of 10 firms to those that failed or required takeover by another public or private entity. That said, there is no established definition of private resolution; the list reflects our subjective judgments. For example, there are firms not on this list of 10 that received extraordinary government support during the crisis.

Finally, a firm breaches the market data thresholds in this regime when its market data signal at the end of a month is above the 95th percentile for all observations of that signal over the past five years for two consecutive months. A firm moves off “breach status” following two consecutive months of having no threshold breaches.

There are alternative ways to construct thresholds. The value of our thresholds, to choose one example, can change month to month. Other regimes use fixed thresholds. We discuss a few alternatives to our approach—and compare our approach to that of the Fed proposal—in Appendix 3.

III. Performance of Market Data Thresholds in the Pre- and Post-Crisis Periods

We review the performance of sample market data thresholds before, during and after the financial crisis. (The page linked to here provides a timeline of key events during the recent crisis.) We review the performance for select, large problem financial firms resolved by public or private means during the crisis. We also examine the performance for large banks targeted by the proposal.

Our main findings are as follows:

- Threshold breaches indicated the systemic nature of the crisis near its inception.

- The thresholds were breached for many resolved firms, as well as some unresolved firms, before or at the very earliest stages of the financial crisis.

- Mass threshold breaches ended shortly after the Federal Reserve completed its Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (SCAP) in mid-2009.

- Firms with substantial investment banking operations—and a few others—had significant numbers of threshold breaches in the post-crisis period, particularly during the fall of 2011.

In total, we believe this evidence supports the use of market data thresholds along the lines proposed by the Federal Reserve. We come to this conclusion because (a) the thresholds generally are breached in a timely fashion for firms that ultimately prove weak and are not breached excessively for firms that ultimately prove not weak and (b) the market-based data seem to complement supervisory assessments. (See Section IV for a discussion of this latter point.) Later in this section, we explain why we support the proposal even if it could erroneously identify a strong firm as weak.

Threshold Results: Pre-Crisis

We highlight two main features of the threshold breaches at the onset of the financial crisis and report our results for the pre-crisis period in Table 1 on the timeline.

- Virtually all 10 resolved firms breach their market data thresholds continuously from early/mid-2007 to their resolution. About one-third of the nonresolved large banks started similar extended periods of breached thresholds during early 2007. The remaining nonresolved large banks moved to prolonged threshold breach status by early fall 2007.

- Seven of the 10 resolved firms had a threshold breach during the period from March 2006 to January 2007. We would consider, by way of context, April 2007 an extremely early dating of the onset of the financial crisis. Five of these seven had at least one threshold breach at or before September 2006. Sixteen of the 23 nonresolved large banks had a breach by April 2007.

We come to two conclusions based on this record, both of which we think support inclusion of market data thresholds in supervision:

- Threshold breaches indicated the systemic and serious nature of the financial crisis at its onset. The Federal Reserve took unusual steps to encourage bank use of its standing lending facility in August 2007; the Fed was clearly aware of and acted on disruptions to bank funding and financial markets at that point. But widespread and sustained breaching of market data thresholds during the summer of 2007 should have raised the potential for a broad-based solvency crisis in banking to supervisors at that point. Thresholds could have reinforced the need for supervisors to take broad action.6

- The thresholds could have potentially provided early warning for select firms. Consider the five independent investment banks at the epicenter of the financial crisis. All but Merrill Lynch breached the threshold at least once before November 2006; Goldman Sachs was in breach status for most of 2006, and Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers both breached their thresholds for at least six consecutive months in 2006. There were other sporadic threshold breaches of a similar vein: Citigroup breached its threshold in November 2006 and continued to have breaches for almost the rest of the crisis, for example.

The early warning record is certainly mixed. Some might think the warnings noted above were not early enough. Other firms that later had severe problems—Freddie Mac, for example—were not continuously breaching their thresholds until the fall of 2007. A few firms that did not receive institution-specific government support during the crisis—Fifth Third Bancorp, M&T Bank Corp. and State Street stand out—are flagged relatively early and often.

We do not view this outcome as inconsistent with our expected outcomes or a reason to not support the proposal for several reasons:

First, determining which banks will end up weak and which will end up strong is very challenging. No system—including the current supervisory system—has historically performed or will in the future perform that sorting flawlessly.

Second, we weigh the benefits of getting it right for a few firms in real time as greater than the costs of getting it wrong for some firms in retrospect. Supervisors could have benefited from several more months to consider their posture to firms that breached thresholds and the financial system entering a crisis; the costs associated with additional discussion of firms that ultimately did not require resolution or other institution-specific government support—which is the response required when firms breach the market data thresholds in the Federal Reserve proposal—seem low to us relative to these potential benefits. Finally, we already noted that market data seem to complement supervisory assessments when the two are compared directly. But market data do not need to be perfect in their assessments or always earlier to identify a problem to help supervisors. Supervisors face substantial uncertainty in their assignments. Our results suggest that market data have relevant information (and other attractive attributes noted below). Responding to market data threshold breaches should reduce the uncertainty that supervisors face.

Second, we weigh the benefits of getting it right for a few firms in real time as greater than the costs of getting it wrong for some firms in retrospect. Supervisors could have benefited from several more months to consider their posture to firms that breached thresholds and the financial system entering a crisis; the costs associated with additional discussion of firms that ultimately did not require resolution or other institution-specific government support—which is the response required when firms breach the market data thresholds in the Federal Reserve proposal—seem low to us relative to these potential benefits. Finally, we already noted that market data seem to complement supervisory assessments when the two are compared directly. But market data do not need to be perfect in their assessments or always earlier to identify a problem to help supervisors. Supervisors face substantial uncertainty in their assignments. Our results suggest that market data have relevant information (and other attractive attributes noted below). Responding to market data threshold breaches should reduce the uncertainty that supervisors face.

Threshold Results: Mid-Crisis

We would expect the thresholds to flash red for virtually all nonresolved large banks when a systemic banking crisis occurs. We find this result (see Table 2 on the timeline). The “wall of red” occurs from January 2008 to a few months after May 2009, the month the Federal Reserve announced the results of the Federal Reserve’s SCAP, or “stress test.” This result is consistent with views that the stress test played a critical role in bringing the financial crisis to an end.7

Threshold Results: Post-Crisis

We run the same thresholds on firms remaining in our sample during the post-crisis period. We report those findings in Table 3 on the timeline, which summarizes results from 2010 to June 2012. We find the following:

- There was another episode during the fall of 2011 where a significant cross section of the large bank universe (about one-third) experienced sustained threshold breaching. This episode coincided with deepening of the European crisis at the time.

- Three types of firms seem to have the most threshold breaches during the post-crisis period:

- Firms with substantial investment banks (e.g., JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley).

- Firms with substantial processing operations (e.g., Bank of New York Mellon, Northern Trust and State Street).

- Bank of America and MetLife.

IV. Threshold Breaches Relative to Changes in Supervisory Ratings and Credit Ratings

We compare historical threshold breaches to changes in certain supervisory ratings of bank holding companies as well as credit ratings. Supervisory ratings and changes to them are the best information we have to make these comparisons. But we stress up front that our approach faces two limitations. One is that ratings are confidential. We cannot reveal ratings of specific firms, for example. We therefore focus on changes across the portfolio because this information does not reveal the actual rating of any firm. The other is that ratings are incomplete measures of supervisory knowledge of firms, assessments of and actions against banks, and overall posture to the banks. Supervisors can be very concerned about and take action against a firm even if they do not lower their ratings.

We find that during the period when there were relatively many threshold breaches for the firms under review, there were relatively fewer, and substantially fewer in some cases, changes in the supervisory ratings given to those firms. This comparison suggests that market data thresholds would be a useful complement to other supervisory assessments of risk. We summarize our findings in this section. We provide more details on the supervisory assessments and formal actions we discuss in this section in Appendix 4.

This comparison reviews a sample of 22 bank holding companies contained in our two groups and reviews two types of supervisory assessments of these BHCs: a composite rating and a single component of that composite, the financial condition rating, or the F rating. Specifically, we review when these two ratings were downgraded in the pre-crisis and crisis periods, and we compare the timing of these downgrades to the timing of market-based threshold breaches reviewed in preceding sections.

This comparison reveals that, although there were across-the-board breaches of market data thresholds in mid-2007, there was just a single composite rating downgrade among these BHCs in 2007. And that downgrade did not lower the firm to “less-than-satisfactory” condition (a rating of 3 or worse on a 5-point scale, with 1 being highest or best). There were five downgrades in 2008.8

Similarly, for the same sample of 22 BHCs, there were no financial component rating downgrades from 2005 to 2007, though market data thresholds were suggesting widespread problems by mid-2007; there were nine financial component rating downgrades in 2008, most of them in the middle of the year.

Not commenting on the actual level of ratings across all firms leaves open the option that firms did not receive downgrades in the 2005-08 period because they already had ratings indicating weakness. We address this potential in two ways.

- Bank supervisors have to make public legal “formal” actions that they take against a BHC.9 Often, but not always, a BHC with a weak composite rating (4 or 5 on the 5-point scale) has a formal action; BHCs can also have formal actions without such a weak rating. Only four firms in this group had a formal agreement during the 2005-2008 period, mostly related to factors not directly related to financial weakness.

- The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) made ratings available for three of the most troubled firms and commented more generally on BHC rating trends for large firms. We repeat that information in Box 3 below, which suggests that firms did not have weak ratings when the thresholds were breached.

In addition, credit ratings for the sample firms in the 2005-08 period are available from Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s.10 All 23 firms had ratings from S&P and 17 had ratings from Moody’s. In Table 4 below, we see that S&P and Moody rating downgrades occurred in 2008, well after breaches of market data thresholds had already highlighted the systemic nature of the crisis.

Box 3

Discussion of Select Holding Company Ratings in Report of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commissiona

The following direct quotes from the Report of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) provide information on rating changes and the absolute ratings levels for select large banks.

General Trends in Large Firm Ratings

By the end of 2007, the FDIC had 76 banks, mainly smaller ones, on its “problem list”; their combined assets totaled $22.2 billion. (When large banks started to be downgraded, in early 2008, they stayed off the FDIC’s problem list, as supervisors rarely give the largest institutions the lowest ratings.)a

As the commercial banks’ health worsened in 2008, examiners downgraded even large institutions that had maintained favorable ratings and required several to fix their risk management processes. These ratings downgrades and enforcement actions came late in the day—often just as firms were on the verge of failure. In cases that the FCIC investigated, regulators either did not identify the problems early enough or did not act forcefully enough to compel the necessary changes.b

AIG

In March [2008], the Office of Thrift Supervision, the federal regulator in charge of regulating

AIG and its subsidiaries, downgraded the company’s composite rating from a 2, signifying that AIG was “fundamentally sound,” to a 3, indicating moderate to severe supervisory concern. The OTS still judged the threat to overall viability as remote.c

Citigroup

For Citigroup, supervisors at the New York Fed, who examined the bank holding company, and at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, who oversaw the national bank subsidiary, finally downgraded the company and its main bank to “less than satisfactory” in April 2008—five months after the firm’s announcement in November 2007 of billions of dollars in write-downs related to its mortgage-related holdings. The supervisors put the company under new enforcement actions in May and June. Only a year earlier, both the Fed and the OCC had upgraded the company, after lifting all remaining restrictions and enforcement actions related to complex transactions that it had structured for Enron and to the actions of its subprime subsidiary CitiFinancial, discussed in an earlier chapter. “The risk management assessment for 2006 is reflective of a control environment where the risks facing Citigroup continue to be managed in a satisfactory manner,” the New York Fed’s rating upgrade, delivered in its annual inspection report on April 9, 2007 had noted. “During 2006, all formal restrictions and enforcement actions between the Federal Reserve and Citigroup were lifted. Board and senior management remain actively engaged in improving relevant processes.”e

In April 2008, the Fed and OCC downgraded their overall ratings of the company and its largest bank subsidiary from 2 (satisfactory) to 3 (less than satisfactory), reflecting weaknesses in risk management that were now apparent to the supervisors.f

Wachovia

On the same day as the announcement [July 22, 2008], S&P downgraded the bank, and the Fed, after years of “satisfactory” ratings, downgraded Wachovia to 3, or “less than satisfactory.”g

a See the Report of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission.

b Report of the FCIC, p. 301

c Report of the FCIC, p. 302

d Report of the FCIC, p. 274

e Report of the FCIC, p. 302

f Report of the FCIC, pp. 303-04

g Report of the FCIC, p. 305

V. Challenges in Supervisory Use of Market Data as Thresholds

In the preceding section, we presented evidence that market data thresholds are a useful source of information for the supervisors of financial institutions. At the same time, though, it is important to keep in mind that market data have potential pitfalls. The challenges concern (a) potential for market signals to convey “noise” rather than information on the condition of firms and (b) potential for gaming market signals.

We review these challenges in some detail for two reasons. First, they help inform our view as to the appropriate response to breaches of market data thresholds. The Federal Reserve proposal requires an additional supervisory review of firms that breach market data thresholds. It does not require, as is mandated for other types of nonmarket threshold breaches, hard and fast changes in bank operations such as restrictions on capital distributions like dividends. We think our limited experience with these thresholds suggests a slow start; we would not support mandatory action in response to market data thresholds at this point.

The way to address this concern and our second reason for listing the challenges in detail is to motivate our recommendations for additional analysis and research, which we discuss in Section VI. We see the challenges as issues to address rather than insurmountable weaknesses. Indeed, is it not clear if challenges in supervisory use of market data loom particularly large relative to those facing more traditional supervision, particularly in light of the latter’s pre-crisis track record.

Noise Versus Information

The use of any data in supervision should be conditional on the information the data provide. Supervisors should not use data that provide no information or, worse yet, provide information not correlated with the true condition of a firm (i.e., “noise”). All data used by supervisors can have some noise. To offer a few examples:

- Some standard accounting data on loan performance can mask high default rates when the volume of loans grows quickly.

- Supervisory and firm assessments of the quality of loans have proven misleading at times, not recognizing future repayment weakness in a timely manner.

- Firm and supervisory measures of liquidity have wrongly suggested that a firm was well positioned to fund itself right before it was not.

Market data naturally have noise as well. We highlight four important sources of noise in market signals (not in order of importance).

1. Microstructure. The nature of the transactions that generate market signals can introduce noise. Some markets have such limited transactions that the market signal used is a quote—the price at which a dealer says it would conduct a transaction—and not an actual transaction price. In other cases, there are only a few true transactions. The absence of many actual transactions and quotes raises questions if the signal fully reflects the views of market participants.

Having just a few transactions in a bond, for example, may also lead investors to demand a premium to buy the security (to compensate for having few buyers when they want to sell). This premium shows up in market prices even though it may not be related to the risk of the bank. Other nondefault-related factors, such as taxes, can influence market signals.11

2. Perceived Government Support. Investors take into account the potential riskiness of a firm if they have money at risk. Perceived government commitment to absorb investors’ losses mutes accurate market pricing. The actual risk of a firm would exceed market perceptions of risk when the government shields the market from loss. The data we reviewed in Section II demonstrate that market participants believed themselves at some risk of loss, even after the government provided extensive support to bank creditors. Nonetheless, the perception of support could reduce the degree to which the risk of firms shows up in market signals.

3. Effect of Supervisory Use of Market Signals. We argue for supervisors to inform their actions with market signal information. Market participants may come to expect certain supervisory actions based on market signals. Those actions could, for example, reduce the risk of the firm. Supervisors could require firms with weak market signals to hold more capital or more dependable funding sources.

Market participants would include such expectations of future supervisory action in their pricing decisions. The expectation of supervisory action could therefore alter the signals that markets generate.12

4. Limited Information. Banks can hold difficult-to-value assets. Investors may not have sufficient information to value such assets.13 Market signals may therefore not accurately assess the true condition of firms.

Gaming Signals

Market participants can structure transactions that pay off if supervisors take action against firms. Supervisory use of market signals could encourage such transactions. Consider the extreme case: One bank might wish to drive another out of business. If unusually weak market signals were an input to closure, a bank might try to move markets to breach thresholds, even if those market transactions lost money. An absence of liquidity in a market could make gaming easier to carry out; a small number of transactions can have large effects on prices in illiquid markets. Market signals based on quotes may also present opportunity for gaming.

VI. Research Agenda to Facilitate Greater Use of Market Data in Supervision

We first outline a research agenda for interested parties to enhance use of market signals as a threshold for supervisory action. We then suggest an agenda for interested parties to confront the remaining challenges noted in Section V.

Facilitating Market Signals as Thresholds for Supervisory Action

We view a desirable threshold as one that identifies as many weak firms as outliers as possible and as early as possible given an acceptable number of strong firms mischaracterized as such. The threshold regime should also prove robust. That is, it should prove reliable as an early identifier of weak firms across time and circumstances.

The Federal Reserve’s DFA proposal seeks to implement such a robust regime. But as the proposal makes clear, additional research could help improve the proposed regime. Indeed, in the proposal, the Board of Governors indicated that it would at least annually revisit the specifics of its market data threshold system and seek comment on it.

We Provide a Few Suggestions for Threshold Research.

As a first step, researchers should develop multiple alternative threshold structures and examine how they tie to supervisory objectives. For example, some structures might do best at figuring out which highly rated firms will become 3 rated or worse a year in advance. Other systems might do better at identifying when weak firms become healthy. Still other thresholds may do best signaling systemic problems across many banks. The Federal Reserve would have more information when modifying the proposed threshold regime if researchers developed more regimes with clear conceptual links to supervisory objectives.

Second, analysts should gather as much market data as possible to test potential thresholds in as robust a fashion as possible. This testing should occur in an “out-of-sample” framework. This means that the actual data that supervisors would have had in the past are tested in “real time” as if supervisors did not have advance knowledge of the future. This environment is as close to reality as analysts can get. Analysts should test the data across as many years as they can, particularly years that have outcomes supervisors want to avoid. Moreover, the tests should occur across as many comparable countries as they can to broaden the review.

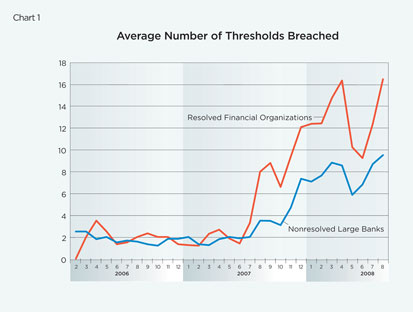

In these comparisons, researchers should look at the performance of specific market sources of information and construction of the threshold. Do credit default swaps perform better or worse as thresholds than equity-based thresholds? Does a change threshold perform better than one based on absolute values? Tables 5 through 7 and Charts 1 through 3 provide additional data on the breaching of the thresholds we review based on their construction and source to further such analysis.

There are also a variety of more narrow and technical areas for additional analysis, some of which are raised in the DFA proposal.14

Finally, as discussed in Box 1, the market data threshold system is one of several thresholds to identify large banks that require increased supervisory review and action in the Federal Reserve’s proposal (the others are not market-based). Researchers should explore the relative expected performance across these thresholds when considering if and how to modify them.

We listed four sources of noise in Section V. We suggest potential approaches for addressing these same four. We also raise some options for addressing challenges of gaming.

Addressing Noise Concerns

1. Microstructure. There are several research agendas that could help shed light on microstructure concerns. While there is natural concern about using quotes instead of actual trades, there is also relatively little analysis comparing quotes versus trades.15 We may find that quote levels match up well with actual prices. Moreover, the changes in quotes may prove very similar to the changes in prices. A systematic comparison of the two is in order.

In addition, a variety of techniques try to tease out the liquidity premium in prices and/or make adjustments to market prices to account for illiquidity.16 These techniques have not been applied systemically to the full range of market signals used by supervisors. Such application seems like a reasonable step, although certainly no guarantee to fix concerns.

At the same time, we encourage more simple analysis. Analysts should document on a regular basis the level of trading in the financial markets from which market signals come, as well as other measures of liquidity. Background on the degree of liquidity in financial markets could help analysts choose which signals to track. Data on liquidity gathered at very high frequencies (e.g., daily) might also lead to simple steps, such as modifying data from a particularly illiquid day, that could make market data more robust. Providing supervisors with rules of thumb grounded in analysis to start addressing illiquidity would be quite beneficial.17

2. Perceived Government Support. Aspects of the approach just outlined for addressing concerns about microstructure/liquidity could help adjust for other factors present in market signals that obscure the risk of loss for a specific financial firm. Analysts have developed measures of the implied support banks receive from governments, for example.18 Analysts could therefore adjust at least some signals to account for perceived support.

3. Effect of Supervisory Use of Market Signals. We noted that the anticipation of supervisory use of market data changes investors’ perception of risk. Those advancing the argument note several conditions under which this theoretical concern would not hold. For example, the concern could be obviated if supervisors look across many markets, which they do. Thus, we view this general concern as secondary in importance.

4. Limited Information. More publicly available information on banks seems the most direct path to more informed investors. Banks themselves could disclose additional information. Banks and bank supervisors have repeatedly called for enhanced disclosure to improve the quality of market signals and the discipline market forces exert on banks.19 Analysis of the key material on banking exposures that markets do not have and which would improve the quality of market prices should be helpful.

Supervisors have also increased their disclosures on bank riskiness by releasing certain facts about how banks perform on the supervisory stress test.20 It would be useful to understand if and how such releases inform market prices. Additional analysis of the pros and cons of releasing additional supervisory information about the riskiness of firms may also prove helpful.21

Gaming

Some of the research agenda just noted would help policymakers consider the potential for gaming in supervisory use of market data. We noted that gaming seems most likely in illiquid markets. Research on illiquidity should clarify if and how to account for that trait and which types of signals may prove less amenable to gaming.

Concern about market manipulation certainly goes beyond supervisory use of market data. Supervisors may first wish to determine if and how to learn from other experiences, such as use of market prices to set certain electrical rates.22 Such experiences may help determine how to structure rules, penalties and monitoring for supervisory use of market signals.

Research could also focus on surveillance and reporting methods to try to detect and deter gaming.23

There may also be fairly straightforward approaches that reduce incentives or ability to game. Not spelling out the process by which supervisors use market data could reduce the threat of manipulation.24 Likewise, relying on many market signals or lowering the severity of the supervisory response to market signals should drive down the returns to gaming. These steps could, however, reduce the benefits from use of signals. Analysis of these costs and benefits would be constructive.

VII. Conclusion

A Federal Reserve proposal would further increase supervisory use of market data by using market data thresholds to enhance supervision. We provided empirical support from the crisis period for such enhancements. We also articulated a research agenda to further the use of market signals in supervision.

Endnotes

1 We use “banks” to refer to banks or bank holding companies. We use the term “bank holding companies” to refer specifically to such firms.

2 We use “financial market signals” to mean prices of financial instruments related to banks, including but not limited to signals related to equity, derivatives and fixed income obligations of banks. Quantities from financial markets can also convey information, but we do not explore that feature of market data in this essay.

3 We focus in this essay on market signals on supervised financial institutions. Supervisors could, and do, use market signals to assess the condition of firms to which financial institutions have exposure.

4 See Federal Reserve System (2012).

5 We restrict this list of 10 firms to those that failed or required takeover by another public or private entity. That said, there is no established definition of private resolution; the list reflects our subjective judgments. For example, there are firms not on this list of 10 that received extraordinary government support during the crisis.

6 The president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston noted in 2010 the potential gains from more timely supervisory action during the initial phase of the financial crisis. “The 2007 events did not lead to similarly significant changes in supervisory policy. The dividends on common stock declared by the largest banking organizations (the 19 SCAP participants and others) actually increased in the 4th quarter of 2007, and did not show dramatic reductions until after the financial crisis hit a crescendo in the fall of 2008.” (See Rosengren 2010.)

7 The stress test was conducted on domestic bank holding companies with assets of $100 billion or greater as of year-end 2008. See the press release at federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/bcreg/20090507a.htm. For a discussion of the SCAP and its role in addressing the financial crisis, see Bernanke (2010). The stress test could have reduced market concerns about banks in at least two ways: by providing participants with new information on the condition of the firms and/or by providing the firms with additional government support. We do not assess the relative contribution of the two factors. See Peristiani, Morgan and Savino (2010) for a discussion of the information provided by the stress test to markets.

8 We also review composite rating downgrades in 2005 and 2006 to determine if the absence of action in 2007 and 2008 reflects prior moves. It does not. There were no downgrades in this group in 2005 and 2006.

9 For more general discussions of enforcement actions, see Alvarez (2012) and Brunmeier and Willardson (2006).

10 These ratings are the long-term, local currency issuer ratings.

11 See Elton et al. (2001) for a discussion of the factors that influence the spread between corporate bonds and Treasury securities. They note that credit risk explains a small portion of that spread. Equity-based measures can, in some cases, also have features that induce noise.

12 See, for example, Bond, Goldstein and Prescott (2010).

13 For a discussion of the opaqueness of banks, see Morgan (2002) and Flannery, Kwan and Nimalendran (2010).

14 A few examples of these more technical areas of research include determining the optimal methods for calculating thresholds based on idiosyncratic measures of market data; comparing the relative benefits and costs of fixed thresholds versus time-varying thresholds, which we discuss in Appendix 2; and using statistical techniques to isolate common signals across the many market data thresholds (thereby allowing a reduction in the number of signals tracked and reported).

15 One paper that does look at the details of market data reporting across data sources is Mayordomo, Peña and Schwartz (2010).

16 For one example among many, see the page linked to here.

17 In this vein, we did require a minimum number of data observations in the sample threshold regime we reviewed. (See Appendix 2.)

18 For a recent example, see Noss and Sowerbutts (2012).

19 In 2001, for example, the Federal Reserve established a working group of private sector experts to encourage additional disclosures from banks. See the press release at federalreserve.gov. Enhanced disclosure by banks has also been a cornerstone of international supervisory efforts. See also the new disclosure task force established by the Financial Stability Board.

20 For a discussion of stress tests and disclosure, see Tarullo (2012).

21 For examples, see Prescott (2008). For a more positive view, see Feldman, Jagtiani and Schmidt (2003).

22 See, for example, the lessons learned from Borenstein et al. (2008).

23 For one example, see data analysis by Snider and Youle (2010) that suggested unusual quotes in the LIBOR panel.

24 An extensive comment letter from five industry representatives raised concern about potential manipulation of market-based thresholds, but suggested that less public disclosure of market data thresholds could potentially address these concerns. See the April 27, 2012, comment letter from the The Clearing House and others. To review all of the comments on the proposal, see the Freedom of Information Office page.

References

Alvarez, Scott G. 2012. “Settlement Practices.” Testimony before the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, D.C., May 17.

Bernanke, Ben S. 2010. “The Supervisory Capital Assessment Program—One Year Later.” Speech at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago 46th Annual Conference on Bank Structure and Competition, Chicago, Ill., May 6.

Borenstein, Severin, James Bushnell, Christopher R. Knittel and Catherine Wolfram. 2008. “Inefficiencies and Market Power in Financial Arbitrage: A Study of California’s Electricity Markets.” Journal of Industrial Economics 56 (June).

Bond, Philip, Itay Goldstein and Edward Simpson Prescott. 2010. “Market-Based Corrective Actions.” Review of Financial Studies 23 (2): 781-820.

Brunmeier, Jackie, and Niel Willardson. 2006. “Supervisory Enforcement Actions Since FIRREA and FDICIA.” Region (September). Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Elton, Edwin J., Martin J. Gruber, Deepak Agrawal and Christopher Mann. 2001. “Explaining the rate spread on Corporate Bonds.” Journal of Finance 56 (February).

Federal Reserve System. 2012. “Enhanced Prudential Standards and Early Remediation Requirements for Covered Companies.” Federal Register 77 (3), Jan. 5.

Feldman, Ron J., Julapa A. Jagtiani and Jason Schmidt. 2003. “The Impact of Supervisory Disclosure on the Supervisory Process: Will Bank Supervisors Be Less Likely to Downgrade Banks?” In Market Discipline in Banking: Theory and Evidence, George G. Kaufman, ed., Elsevier.

Feldman, Ron J., and Mark Levonian. 2001. “Market Data and Bank Supervision: The Transition to Practical Use.” Region (September). Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Feldman, Ron J., and Arthur J. Rolnick. 1998. “Fixing FDICIA: A Plan to Address the Too Big to Fail Problem.” 1997 Annual Report. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Ferguson, Roger W. Jr. 2000. Interview. Region (June). Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Flannery, Mark J., Simon H. Kwan and Mahendrarajah Nimalendran. 2010. “The 2007-09 Financial Crisis and Bank Opaqueness.” Working Paper 2010-27, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Furlong, Frederick T., and Robard Williams. 2006. “Financial Market Signals and Banking Supervision: Are Current Practices Consistent with Research Findings?” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Review.

Greenspan, Alan. 2001. “Harnessing Market Discipline.” Region (September). Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Mayordomo, Sergio, Juan Ignacio Peña and Eduardo S. Schwartz. 2010. “Are all Credit Default Swap Databases Equal?” Working Paper 16590, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Morgan, Donald P. 2002. “Rating Banks: Risk and Uncertainty in an Opaque Industry.” American Economic Review 92 (September).

Noss, Joseph, and Rhiannon Sowerbutts. 2012. “The Implicit Subsidy of Banks.” Financial Stability Paper 15, Bank of England.

Peristiani, Stavros, Donald P. Morgan and Vanessa Savino. 2010. “The Information Value of the Stress Test and Bank Opacity.” Staff Report 460. Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Prescott, Edward Simpson. 2008. “Should Bank Supervisors Disclose Information About Their Banks?” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly 94 (Winter).

Rosengren, Eric S. 2010. “Dividend Policy and Capital Retention: A Systemic ‘First Response.’” Speech at Rethinking Central Banking conference, Washington, D.C., Oct. 10.

Schmidt, Jason. 2004. “Lessons from the Survey: A Review of the Use of Market Data in the Federal Reserve System.” Paper presented at the workshop Supervisory Use of Market Data, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, March 26.

Snider, Connan, and Thomas Youle. 2010. “Does the LIBOR Reflect Banks’ Borrowing Costs?” Working paper.

Stern, Gary H. 2001. “Taking Market Data Seriously.” Region (September). Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Tarullo, Daniel K. 2009. “Financial Regulation: Past and Future.” Speech at the Money Marketeers of New York University, Nov. 9.

Tarullo, Daniel K. 2010. “Involving Markets and the Public in Financial Regulation.” Speech at the Council of Institutional Investors Meeting, Washington, D.C., April 13.

Tarullo, Daniel K. 2012. “Developing Tools for Dynamic Capital Supervision.” Remarks to the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Annual Risk Conference, Chicago, Ill., April 10.