Our Mission

The Community Development Department supports the Federal Reserve System’s economic growth objectives by promoting community development through fair, impartial, and efficient access to credit and related financial services. We support investment in low- to moderate-income communities through information, outreach, and technical assistance. We serve the Ninth Federal Reserve District, which includes Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, northwestern Wisconsin, and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

Introduction

This report presents the findings from a biannual survey of community organizations, including developers, lenders, and service providers, that is designed to provide insight on 17 key indicators related to the economic health of low- to moderate-income (LMI) communities. Information included in this report is based on the front-line observations of representatives of 476 organizations that play a critical role in the development and stabilization of LMI communities in the Ninth Federal Reserve District. Respondents were asked to gauge changes in employment, housing, financial, and business conditions for the communities they serve by comparing current conditions with those that prevailed six months earlier. Collectively, their observations help provide a community-based perspective on issues that are important to the community development work of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and the Federal Reserve System.

Survey respondents included: community banks; non-bank community development financial institutions; public and private economic developers; state workforce and job service centers; housing developers and housing service providers; including government agencies; small business technical assistance providers; Community Action Agencies and other organizations that provide basic-needs assistance; financial education providers; trade associations; tribal organizations; university extension services; community foundations; neighborhood organizations; and other nonprofit entities. The geographic locations of respondents were widely dispersed, representing more than 290 cities, townships, and reservation areas across the Ninth District.

State |

Proportion of Respondent Pool |

Proportion of Ninth District Population* |

Michigan (UP) |

4% |

4% |

Minnesota |

38% |

59% |

Montana |

14% |

11% |

North Dakota |

16% |

7% |

South Dakota |

19% |

9% |

Wisconsin (NW) |

8% |

10% |

*Based on 2007–2011 American Community Survey five-year estimates. |

||

Respondents were asked to gauge changes in LMI community conditions using the response categories “decreased,” “stayed the same,” or “increased.” They were also invited to elaborate on their responses by providing comments. Respondents were instructed to answer questions based on firsthand observations and were encouraged to answer “don’t know” if they were not knowledgeable about an issue in the community. For each question, those who answered “don’t know” were excluded from the analysis.

Information for Ninth District Insight was gathered through an online survey developed and administered by the Community Development Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Responses included in this report were collected during the months of July and August 2012. Forty-five percent of respondents were participants in the previous poll conducted during the fourth quarter of 2011.

One change in the survey population for second quarter 2012 is the first-time inclusion of community banks. Responses from community banks differed from those of other respondents on question items related to housing, consumer debt, and business access to credit. Some of the more material differences between community bank and non-bank respondents are noted in this report.

Percentages reported are for valid responses only, unless otherwise noted. Numbers might not equal 100 due to rounding. Caution should be used when interpreting the numbers for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan as they represent fewer than 20 cases.

LMI Economic Conditions at a Glance

Based on survey responses, most indicators of LMI community economic well-being remain negative for the Ninth District overall, but they are less negative than observances for fourth quarter 2011. Information gathered from survey participants shows continued overall deterioration in community conditions for the past two survey periods. Indicators that remain the most negative Districtwide are:

- Demand for financial counseling in LMI communities;

- Number of formerly middle-class households seeking assistance from LMI community organizations;

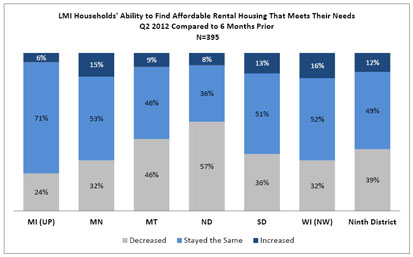

- LMI households’ ability to find affordable rental housing that meets their needs; and

- Ability of business owners in LMI communities to recruit and retain workers with the “right” skills.

Survey results also point to some signs of improvement in economic conditions for LMI communities across the Ninth District. Indicators that showed increased overall improvement in comparison to six months ago were:

- Businesses seeking new loans or lines of credit in LMI communities in Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and western Wisconsin;

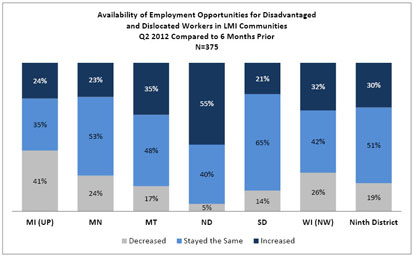

- Employment opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities in Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and western Wisconsin;

- Job training opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities in Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and western Wisconsin; and

- Business closings and bankruptcy filings in LMI communities in Montana and North Dakota.

LMI Economic Index Second Quarter 2012 |

|||||||

The LMI Economic Index measures overall change in community conditions. The Index ranges from 0 (most deterioration in conditions) to 200 (most improvement in conditions) where a value of 100 equals neutral. A number less than 100 indicates overall deterioration and a number greater than 100 indicates overall improvement. Indicators are ordered from greatest Districtwide deterioration to least Districtwide deterioration based on second quarter 2012 survey responses. Index values for fourth quarter 2011 are provided in parentheses for comparison where available. |

|||||||

|

Ninth District |

MI (UP) |

MN |

MT |

ND |

SD |

WI (NW) |

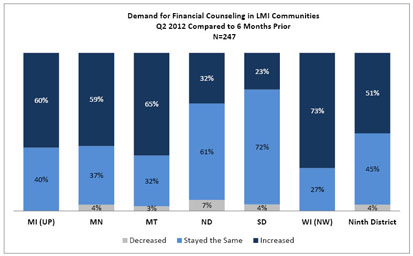

Demand for financial counseling in LMI communities |

54 |

40 |

45 |

38 |

75 |

81 |

27 |

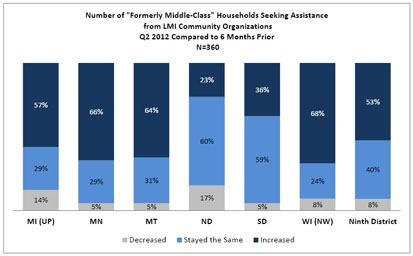

Number of formerly middle-class households seeking assistance from LMI community organizations |

55 |

57 |

39 |

41 |

94 |

69 |

40 |

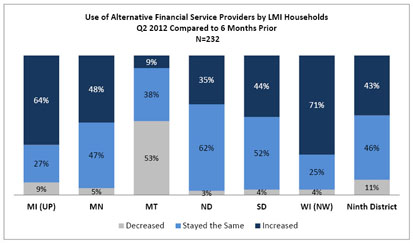

Use of alternative financial service providers by LMI households |

68 |

45 |

57 |

144 |

68 |

60 |

33 |

LMI households’ ability to find affordable rental housing that meets their needs |

73 |

82 |

83 |

63 |

51 |

77 |

84 |

Ability of creditworthy LMI households to obtain a mortgage |

74 |

100 |

81 |

58 |

67 |

79 |

62 |

Ability of business owners in LMI communities to recruit and retain workers with the “right” skills |

74 |

64 |

79 |

80 |

68 |

78 |

46 |

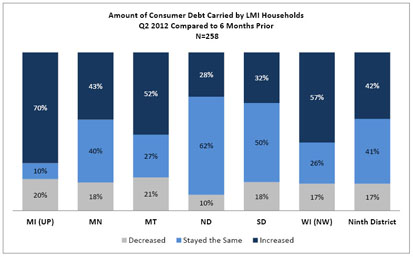

Amount of consumer debt carried by LMI households |

75 |

50 |

75 |

69 |

82 |

86 |

60 |

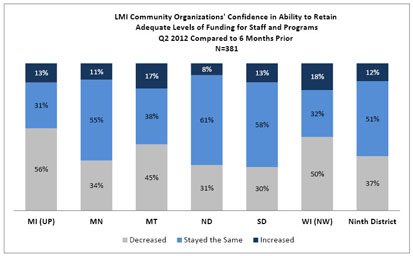

LMI community organizations’ confidence in ability to retain adequate levels of funding for staff and programs |

75 |

57 |

77 |

72 |

77 |

83 |

68 |

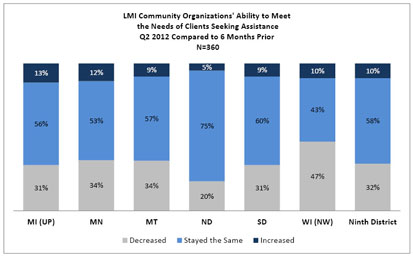

LMI community organizations’ ability to meet the needs of clients seeking assistance |

78 |

82 |

78 |

75 |

85 |

78 |

63 |

Access to credit for business owners in LMI communities |

87 |

120 |

80 |

76 |

115 |

95 |

59 |

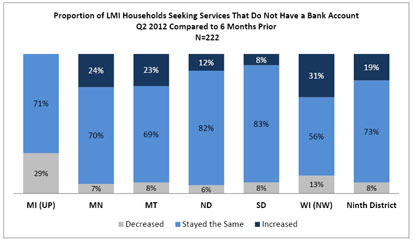

Proportion of LMI households seeking services that do not have a bank account |

89 |

129 |

83 |

85 |

94 |

100 |

82 |

Business closings and bankruptcy filings in LMI communities |

92 |

72 |

73 |

104 |

132 |

100 |

68 |

Number of vacant and foreclosed properties on the market in LMI neighborhoods |

101 |

84 |

86 |

92 |

156 |

97 |

90 |

Job training opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities |

106 |

85 |

103 |

111 |

113 |

104 |

110 |

Business openings in LMI communities |

107 |

109 |

94 |

107 |

148 |

100 |

100 |

Employment opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities |

111 |

83 |

99 |

118 |

150 |

107 |

106 |

Businesses in LMI communities seeking new loans or lines of credit |

120 |

110 |

119 |

130 |

128 |

116 |

100 |

How the LMI Economic Index is calculated |

|||||||

Following is an in-depth analysis of survey results, including state-by-state comparisons and illustrative quotes from respondents.

Employment and Job Training

Opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers

Survey results indicate overall improvement in employment opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers; however, much of that growth can be attributed to activity in the Bakken oil region that has yielded new jobs in construction, hospitality, and retail services. Not all of the byproducts of the oil boom have been positive. Respondents in the Bakken report that the industry has adversely impacted other industries by creating wage pressures and labor shortages for those that rely on workers with similar skill sets. In addition, insufficient infrastructure and the shortage of workforce housing continue to create problems for local governments and limit opportunities for families.

The majority (70%) of respondents reported that the availability of employment opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities has either remained the same or decreased over the past six months. According to respondents, federal and state budget cuts have negatively impacted job growth, the jobs that are available for dislocated workers pay insufficient wages, and unemployment remains high among older workers without post-secondary education.

“Employment opportunities in the Bakken have been a mixed blessing for northwest Montana workers and families. For those able to make the commute and find affordable housing, the oil fields offer badly needed, well-paying jobs. At the same time, the outflow of workers and equipment represents a significant loss of capacity in forestry and land management. It is becoming more difficult to find qualified contractors to do hazardous waste reduction or forest health treatments.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, MT

“We have lost several businesses in the last couple of years. We have gained a Walmart, which hires many [people] from outside of this area. We have a local hospital that has cut jobs due to cuts in Medicare and Medicaid, and our school system has also laid off teachers due to state government cuts.”—Respondent in rural area, MN

“Jobs at the lower end remain in short supply, and there is often a mismatch between the [location of] job opportunities and affordable housing, making it difficult for workers to maintain both employment and housing stability.”—Respondent in urban area, MN

Survey results show overall improvement in the number of job-training opportunities for disadvantaged and dislocated workers in LMI communities over the past six months. However, declines in state funding for job-training programs and unfavorable market conditions continue to remain a challenge. Respondents also commented on employers’ apparent unwillingness to provide on-the-job training despite their inability to fill posted positions.

“The workforce groups in our area have stepped up training opportunities for [residents in] low- to moderate-income communities.” —Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, MN

“One of the biggest barriers [to employment] is employer expectations. Employers have gotten to a point where they want a very specific combination of skills in the people they hire, and they don't want to provide on-the-job training. Nor are they willing to raise starting wages for the positions they are having a hard time filling.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, MN

Housing

Affordable rental opportunities, access to mortgage loans, and foreclosure recovery

Across the Ninth District, respondents continued to express concern over the short supply of affordable rental housing and cuts to federal housing programs, including the HOME Program. Most respondents (89%) reported that the ability of LMI households to find affordable rental housing that meets their needs has either remained the same or decreased over the past six months. Districtwide, several respondents commented on the slow or complete lack of construction of affordable rental housing in their communities.

“We work with low-income job seekers, many of whom need [affordable] housing. Few or no options exist in western Wisconsin. The waiting lists for public housing programs [are long]. For some people, living in a rundown trailer home is the only available option.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, WI

“Employment opportunities are numerous, but we have been unable to hire teachers or law enforcement personnel due to lack of housing. Numerous “man camps” have been built to provide housing for oil field workers. New homes and apartments are being constructed to provide adequate housing, [but the pace is not quick enough].”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural, ND

“We have recently experienced a major flood that impacted our housing stock. There will be more investment in the renovation of homes, but the rental housing vacancy rate is very tight and the flood has further increased the need for more decent, affordable rental units.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, MN

“We have a significant housing shortage for low- to middle-income [workers] in our community.”—Respondent in rural area, SD

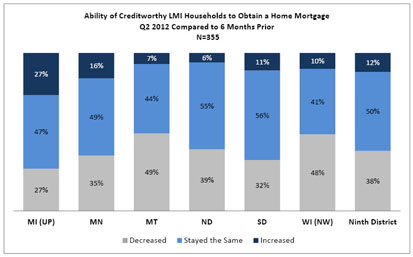

Survey responses indicate that despite low interest rates, homeownership opportunities for LMI households have either remained the same or declined over the past six months. Districtwide, more than one-third (38%) of respondents reported a decrease in the ability of creditworthy LMI households to obtain a mortgage. Community bank respondents were more likely to report no change on this measure, while non-bank respondents were more likely to report a decline. Several respondents, both community banks and non-banks, cited new regulatory and underwriting requirements as the chief reasons why households are not able to obtain a loan.

Many also commented on the large number of LMI households with underwater mortgages preventing them from refinance or sale. Also, a small number of respondents mentioned that immigrant households have been unable to take advantage of foreclosure assistance programs due to language barriers and low financial literacy.

“In rural communities it has become much harder for consumers to obtain funding for housing due to increased regulation. Also, there are fewer organizations that are willing to do residential real estate loans.”—Respondent in rural area, SD

“Our bank discontinued offering residential mortgage loans as a result of the increased regulatory burden. We are trying to find ways to meet the need, but it has been very difficult. It would serve everyone well if we could lend money to creditworthy customers at terms that are beneficial to [both] the customer and the bank without worrying about the regulatory risk.”—Respondent in rural area, ND

“Appraisals are coming in lower, especially in struggling neighborhoods. We've had a number of members contact us after FHA has lowered the appraised value of a home. This places a significant burden on homeowners who are current on their mortgage and wish to sell.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, MN

“Low-income and immigrant [residents] who do not have financial literacy skills are unable to tap into resources to assist with mortgage foreclosure relief.”—Respondent in urban area, MN

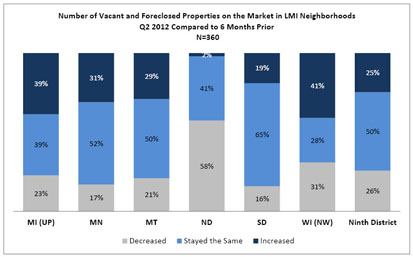

Survey responses indicate little or no change in the overall number of vacant and foreclosed properties on the market in LMI neighborhoods over the past six months. However, conditions appear to vary across the District. More than half (58%) of the respondents based in North Dakota reported decreases compared to less than one-third of the respondents for all other states. According to respondents, LMI households are continuing to fall into foreclosure due to loss of income and a lack of qualified buyers is preventing the absorption of foreclosed properties. Community banks were more likely to report a decrease in vacant properties than non-bank respondents.

Household Financial Well-Being

Consumer debt, financial counseling, and the use of alternative financial services

Most respondents (83%) said that, in the LMI communities they serve, the amount of consumer debt households are carrying has either stayed the same or increased over the past six months. According to respondents, many LMI consumers are relying on credit to pay for basic living needs such as food, transportation, and health care. Community banks were less likely to report an increase in consumer debt than non-bank respondents.

“[LMI] consumers are using their credit cards for living expenses more than ever before.”—Respondent in rural area, MI

“Many consumers continue to turn to credit cards and spend beyond their ability to repay. In turn, they default on that credit, which results in [a decline in] their ability to obtain credit in the future. This is a real crisis.”—Respondent in rural area, MN

In surveying consumer credit conditions, we also asked about households’ use of alternative financial services, such as payday lenders. In all states except Montana, more than 90 percent of respondents reported that the use of alternative financial service providers by LMI households has either remained the same or increased over the last six months. While in-state payday lending in Montana has essentially disappeared as a result of state legislation passed in 2011, respondents’ comments indicate that some LMI households in Montana are now turning to online payday lenders instead.

“Payday lenders across the river from us in Wisconsin are proliferating.”—Respondent in urban area, MN

“Payday lending has been regulated out of business in Montana, but we have not seen a rash of individuals looking for micro-loans so [it is likely] that payday borrowers have simply shifted to online channels.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, MT

“People are getting caught up in a debt trap by payday lenders offering small dollar loans. We have interviewed clients and most are getting $200 to $500 for emergencies and then can’t pay it off. We asked people if they have emergency savings and most do not.”—Respondent in reservation area, SD

Survey responses suggest that the proportion of LMI households without a bank account continues to remain steady or is on the rise in comparison to six months ago. Districtwide, nearly 1 in 5 respondents reported an increase in the proportion of clients seeking services who do not have a bank account. Among the few who reported a decrease, the move toward electronic deposit of benefits was cited as one reason why more LMI households are utilizing mainstream financial services. Anecdotally, one community bank respondent reported that new requirements have made it more difficult to open accounts for undocumented residents.

Survey results indicate that the demand for financial counseling services in LMI communities across the Ninth District has either remained the same or increased over the past six months. Districtwide, about half of respondents (51%) reported seeing an increase. According to respondents, tighter lending requirements have made people increasingly aware of the need to have good credit and to seek credit repair if they do not. In this respect, some financial educators viewed the increase in the demand for financial counseling as a positive indicator, at least in the short term. As demand has increased, so has the need for more financial counselors. In some rural areas, access to financial counseling is very low.

A few respondents said they have witnessed actual decreases in the demand for financial counseling services in the past six months. According to respondents, in some areas the actual need is low. However, in areas where consumer debt is high, it appears that current programs are not meeting the needs of consumers. Survey responses indicate a need for counseling that is more individualized; counseling that is culturally appropriate, especially in the case of Native American households; and counseling that is designed for households facing emergency financial situations.

“The housing crisis and lack of quality employment opportunities has impacted individual credit and increased the need for financial counseling.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, WI

“Low-income families are stretched to their limit using credit cards for day-to-day living. The only free [financial] counseling available is in the next town over—30 miles away. It is not possible for many [LMI households] to travel there for financial counseling. We need it here.”—Respondent in rural area, MT

“People who could not afford housing before can suddenly do so with the high wages they are pulling in from oil field work. However, because they previously did not manage their credit, they have a lot of repairing to do before they can actually purchase the things they can afford now, [such as a truck or a house].”—Respondent in rural area, MT

Business Conditions

Start-ups and closings, access to credit, and the ability to find qualified workers

Survey results show a continued decline in access to credit for business owners in LMI communities, although conditions appear to be somewhat less negative than they were six months ago. Districtwide, more than one-quarter of respondents (29%) said that the ability of business owners to obtain the amount of credit they need has decreased over the past six months. Community banks were less likely to report a decrease than non-bank respondents.

According to survey responses, the deterioration in access to credit remains particularly challenging for start-ups and less established business owners. Respondents report that some small business owners are continuing to turn to community development financial institutions (CDFIs) to meet their credit needs in place of traditional lending institutions. According to some community banks, tighter regulatory requirements have prevented them from making loans.

Overall, business credit conditions are much more favorable in North Dakota than in other parts of the District. Only 12 percent of respondents in North Dakota reported a decrease in access to credit for business owners in LMI communities over the past six months, compared to one-third or more of respondents in all other states. Additionally, respondents reported that credit conditions have continued to remain favorable for agricultural businesses across the District.

“Because of the tightening of credit by banks, which may finally be loosening a bit after three years, we have seen an increase [in the credit quality of our loan applicants]. Longtime, established businesses and other entrepreneurs are coming to us. Historically, [as a CDFI] we have been a lender of last resort. However, as we have seen better credit [scores] and larger deals, we have been able to partner with banks by matching, or nearly matching, their interest rates. Ultimately, this is a win-win for borrowers.”—Respondent in urban area, MN

“Access to credit is very challenging for small businesses and start-ups. They don't meet the new standards of creditworthiness that it takes to acquire funding. [The same is not] true for larger organizations and businesses that have a good financial track record. Business expansion has definitely increased in the past 12 to 18 months so there is lending occurring. However, this is predominantly being driven by lending to medium and large businesses.”—Respondent in rural area, WI

“Regulatory requirements have had a huge impact on an existing business’s ability to obtain operational credit. Allowance for loan loss requirements and what is now considered an 'impaired loan' by regulators has [decreased] what we can do for our customers. [The fallout] over the last four years has resulted in our lending staff being extremely cautious in their evaluation of all new loan requests.”—Respondent in rural area, MN

“The agricultural [sector] of our economy is very strong and credit is easily secured by requesting borrowers.”—Respondent in rural area, MN

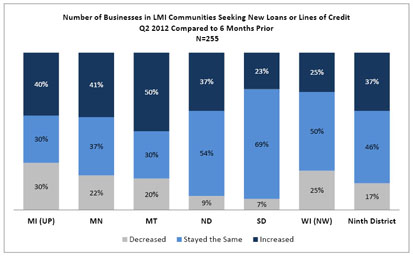

Other indicators of business vitality in LMI communities vary across the Ninth District. Survey responses show an overall increase in the number of businesses seeking new loans or lines of credit over the past six months. Districtwide, more than one-third (37%) of respondents reported an uptick in the number of businesses seeking loans or lines of credit, and in Montana, half (50%) reported seeing an increase. Community banks were less likely to report an increase than non-bank respondents. In areas where loan demand has decreased, respondents cited regulatory and credit issues.

“Commercial loan demand in our area has been fairly strong.”—Respondent in rural area, ND

“We have seen loan demand fall this year, but our percentage of approvals is at an all-time high. Manufacturers are trying to ramp up and are having trouble regaining the credit they had pre-recession due to falling collateral values and decreased profitability in recent years.”—Respondent in rural area, MI

“Business owners are continuing to reduce debt and increase cash reserves until regulatory and tax environments settle down.”—Respondent in rural area, MN

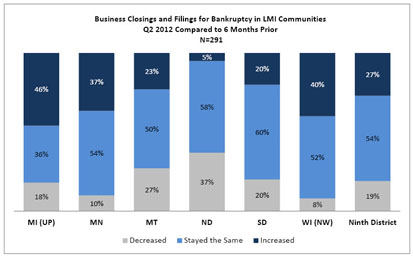

Districtwide, one-quarter (27%) of respondents said that the number of businesses closing or filing for bankruptcy has increased over the past six months, while roughly half (54%) reported that conditions remain about the same. Overall, the Dakotas and Montana appear to be faring better than other states.

“Small businesses are continuing to close in [our county] due to the economic conditions. They are out of cash reserves after the long downturn. However, bankruptcy filings tracked by our institution have declined since the high point in 2009.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, MT

“In [our community], some longtime retail stores are closing, but there are more [Latino-owned] businesses opening.”—Respondent in rural area, MN

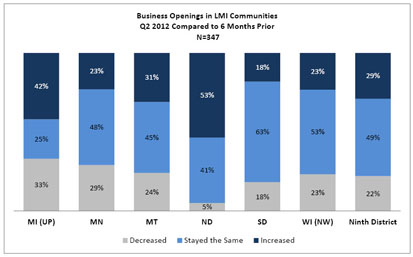

Survey responses indicate overall improvement in the number of business openings in LMI communities across the District. More than one-quarter of respondents (29%) reported an increase in the number of business openings in the communities they serve in comparison to six months ago. For counties located in or near the Bakken oil region, new business is booming. In areas where business openings remain flat, respondents cited the tight credit market, lack of infrastructure, and population decline as primary factors preventing new business growth.

“Business activity is increasing in LMI neighborhoods along emerging transit corridors, [including the] Central Corridor.”—Respondent in urban area, MN

“This past quarter, recreational areas saw growth in the food and beverage industry. Second quarter 2012 resulted in a number of new businesses opening and a warm spring produced strong sales.”—Respondent in rural area, MN

“Business vitality is very good at this time. We have seen many new businesses come into our community and some existing businesses expand. Our bank has programs available for new businesses and business expansions. We have not seen any economic downturn.”—Respondent in rural area, ND

“Business start-ups have slowed [due to] an overall lack of confidence in the economy and more stringent credit requirements.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, MN

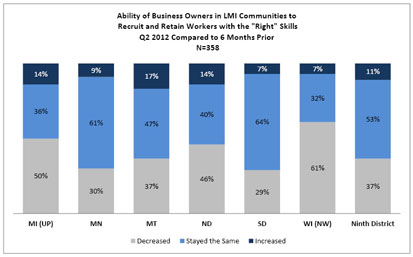

The ability of business owners in LMI communities to recruit and retain workers with the “right” skills continues to remain a challenge, although conditions appear somewhat less negative than in fourth quarter 2011. Districtwide, more than one-third (37%) of respondents reported a decrease in business owners’ ability to recruit and retain workers with the “right” skills compared to six months ago.

In rural communities, there exists an unmet demand for both college-educated professionals and workers with highly specialized manufacturing skills. According to respondents, workforce housing shortages and declining populations make it difficult to recruit qualified applicants. In some areas, even jobs that require less education are going unfilled. Respondents mentioned workers’ apparent unwillingness to work for lower wages and/or relocate for employment. Survey results indicate that North Dakota and Wisconsin may be experiencing greater difficulty with recruitment and retention than other states.

“In our region, it is difficult to attract employees that fit the requirements of technical positions. Engineers, nurses, and other high-wage jobs are posted for months. Low unemployment creates an opportunity for new outside workers to move here, but it has been difficult to recruit and retain them.”—Respondent in rural area, MN

“We have businesses that are eager to move in or expand, but are having trouble locating workers. Part of this is [due to the lack of available] housing. Also, these new jobs pay in the $12 to $15 per hour range and it seems that people are not willing to move for salaries in that range.”—Respondent in rural area, SD

“In western North Dakota, it is becoming more difficult to hire and retain good employees due to the high-paying oil field jobs available.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, ND

“[Lack of] proper job training remains an issue. [Some candidates] are even lacking the soft skills deemed to be important.”—Respondent in rural area, MN

“There exists a large gap between the skills of LMI [job seekers] and the minimum skills required for the jobs that are available.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, WI

Capacity of Community Development and Service Organizations

Funding levels and the ability to meet LMI community service needs

In addition to sharing their perspectives on current economic conditions for the LMI communities they serve, we asked respondents to share their perspectives on their own organization’s financial outlook and ability to meet ongoing community service needs.

Districtwide, more than one-third (37%) of respondents reported decreased confidence in their organization’s ability to retain adequate levels of funding for staff and programs in comparison to six months ago. Survey responses indicate continued concern over government spending cuts. In particular, respondents mentioned the loss of stimulus funding provided by the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and cuts to federal housing programs. A decline in the amount of funding available from philanthropic sources was also a concern. Despite a strong economy and a state budget surplus, it appears that community organizations in North Dakota are not faring any better than those in other states. One-third (31%) of respondents in North Dakota reported decreased confidence in their ability to retain funding for staff and programs.

Some organizations have sought to weather government cuts by diversifying their funding streams, while others have opted to merge with like organizations or develop other strategies for collaboration.

“Federal cutbacks in [funding for] community development programs have impacted LMI community organizations significantly on all fronts, and state cutbacks have exacerbated the issue. Also, foundations have shifted their focus away from capacity building within organizations and decreased the amount of capital available for community organizations. This scenario does not bode well for the future vitality of community service organizations that LMI households rely on for assistance.”—Respondent in rural area, SD

“Like most anti-poverty programs, our funding has been reduced or frozen while costs and demands for service have risen. We have had to lay off staff and consolidate services. Anxieties about future funding have negatively affected morale and inhibited our ability to do reliable strategic planning.”—Respondent in rural area, WI

“Nonprofits are struggling due to lack of funding opportunities, particularly grant funds. The need for services has increased and so has the cost of food pantries, transportation vouchers, and emergency housing. North Dakota is flush with money but little is done with that surplus to assist LMI households directly.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, ND

“We’ve recently lost funding for workforce training. We are looking for ways to [maintain] the capacity we've built up. [The] movement to get workforce training programs to collaborate continues in full force.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, MN

Overall, organizations’ ability to meet the ongoing service needs of LMI communities has either worsened or remained unimproved over the last six months. Despite an increasing demand for services, several organizations have been forced to reduce the number of clients they serve. Others have simply tried to do more with less.

Some entities that provide services to business owners in LMI communities, including technical assistance providers and community banks, also expressed concern about their capacity to meet client needs. For these organizations, increasing operating costs coupled with declining profitability have posed uncertainty regarding sustainability.

“Less funding means less services. Unlike private business, the cost of doing business cannot be passed on to the consumer of our services since financial insecurity is what brought them to us in the first place. We have implemented new ventures to change the dynamics of our funding, but [these measures] will never replace what the state or federal government [previously] invested in these efforts.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, MN

“Our funding sources are fairly stable, but we are trying to do more with less.”—Respondent in reservation area, MT

“We had an influx of service requests in the first half of 2012—nearly double that of last year. We have been forced to select clients that appear to have the most potential for job creation, which leaves many determined entrepreneurs of color without the kind of technical assistance they need in order to succeed in the long term. We work with a continuum of economic development colleagues across the metro in order to try and match people’s needs, but we are all under pressure.”—Respondent in urban area, MN

“We are a typical small-town community bank that was strong enough heading into the recession that we expect to survive it. However, of bigger concern are increasing operating costs, decreasing non-interest income, stale loan demand, and added regulatory expense. It is our belief that the future of small town community banks is in jeopardy.”—Respondent in rural area, MN

Districtwide, more than half (53%) of respondents reported an increase in the number of “formerly middle-class” households seeking assistance in comparison to six months ago. The proportion of respondents who reported seeing more “formerly middle-class” households was highest in Minnesota and Wisconsin (66% and 68%, respectively).

“Demand for services is increasing. Many people with disabilities lost their jobs during the recession and most of [them] need re-training in order to be employable.”—Respondent in mixed urban-rural area, MN

“We have seen an increase in formerly middle class families applying for assistance.”—Respondent in rural area, MN

“The disparity in wealth appears to be widening. More people are dropping out of the middle class as they lose jobs and come back into the market at a lower level of earnings. We have tried to help people by addressing short-term needs, but longer-term solutions remain elusive.”—Respondent in urban area, MN

About Ninth District Insight

The Ninth District Insight Survey is designed to capture front-line observations about issues that affect the economic health of LMI communities. Participants’ responses serve as leading indicators of change in conditions that are otherwise difficult to measure or are not measured through other existing data sources. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis senior leadership and Community Development staff use Ninth District Insight to help identify regulatory and policy issues that deserve attention and to decide how Community Development program resources should be targeted. We hope that the community-based perspective that Ninth District Insight provides also serves as a valuable resource for decision makers outside the Federal Reserve System.

Participation in Ninth District Insight is entirely voluntary and no individually identifiable information is reported. If you would like your organization to be considered for inclusion in the next survey, contact Ela Rausch at ela.rausch@mpls.frb.org.