Fabrizio Perri

The Great Recession was remarkable for both its depth—slumping economic output, plummeting asset prices, heavy job losses—and the similar way it played out across the industrialized world. Output, spending, investment and employment were all hit hard in 2008, both in the United States and in other industrialized countries such as Canada, Japan, Germany and France. It was as if many of the world’s leading economies had jumped off a cliff together.

Recent research by University of Minnesota economist Fabrizio Perri, a consultant to the Minneapolis Fed, and Vincenzo Quadrini, an economist at the University of Southern California, offers an explanation for why nations marched in lock step into the downturn.

In “International Recessions” (Minneapolis Fed Staff Report 463), the authors describe a self-reinforcing process in which tighter credit conditions arise from expected low values for company assets. Tighter credit in turn stunts economic growth. Cross-border financial ties ensure that pessimism takes hold globally, triggering widespread economic woe.

“In a financially integrated world, these expectations are coordinated across countries,” Perri said in an interview. “If a crisis of this type happens, it’s necessarily a global crisis.”

All together now

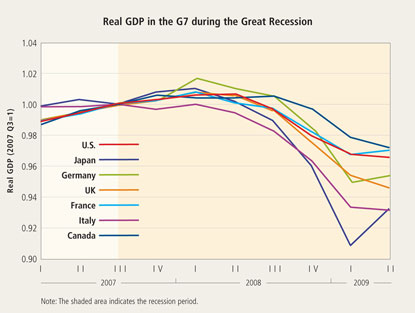

Not since the Great Depression of the 1930s have so many countries moved in such macroeconomic unison as they did during the 2007-09 recession. Perri and Quadrini show, for example, that economic output in the seven largest industrialized countries followed a nearly identical path (see accompanying chart); gross domestic product in the United States and in other Group-of-Seven nations peaked in the first quarter of 2008, then nosedived that fall. Financial markets on three continents also moved as one; in both the United States and the G7, stock prices tumbled and commercial lending fell sharply in the midst of the recession.

Why did the Great Recession affect so many countries at the same time, with similar consequences for firms, workers and investors? The economists attribute this striking global synchrony—and the severity of the recession—to a broad and deep contraction in lending.

Other investigators have studied credit shocks—unexpected changes in the liquidity of capital—as the impetus for international business cycles. But most studies have treated such shocks as originating outside the economy of a particular country. An “exogenous” shock may entail a change in credit conditions—tighter credit access, for instance—in one country that affects the economic performance of other countries.

But such a scenario, in which shocks are transmitted from one country to the next, doesn’t fit the pattern of deteriorating credit conditions during the downturn. If credit had tightened only in one country, domestic firms could have borrowed instead from unconstrained lenders in other countries. But during the recent recession, access to credit diminished in London, Tokyo, Frankfurt and New York, roughly at the same time and in equal measure.

Perri and Quadrini attempt to explain this worldwide credit contraction by proposing an additional “endogenous” mechanism for multinational credit shocks—a seismic shift in the global credit environment made possible by financial bonds among countries.

Altered states

To make their case, the researchers develop a two-country economic model representing the United States and the rest of the G7 in which companies rely on credit to finance hiring and to pay dividends to shareholders. Access to credit in the model depends on how lenders perceive the value of firms’ physical assets—facilities, inventory and other holdings that would be liquidated in the event of a loan default.

When lenders anticipate low resale values for these assets, they withhold credit, fearing that they won’t be able to recover the full amount of loans made to defaulting firms. Constrained credit deprives healthy firms of capital they need to buy the assets of defaulting firms, depressing market prices—and confirming the expectations of lenders. Credit remains tight, forcing firms to lay off workers and causing declines in consumer spending and investment.

Conversely, when lenders expect high resale values for the assets of defaulting firms, they lend freely, keeping market prices high and stimulating hiring and economic growth.

Thus, rational expectations for asset values become self-perpetuating, locking the economy into one of two possible stable states, or equilibria—one with loose credit and the other with tight credit. Crucially, in the model, altered price expectations in one country instantly change expectations and credit conditions in the other, because of the web of cross-border ownership, investment and banking arrangements linking financial markets today.

Perri and Quadrini don’t address why expectations change, but point to the bankruptcy of the Lehman Brothers investment house in September 2008 as a watershed event in the Great Recession. “The Lehman default could be interpreted as the trigger that switched the world economy from an equilibrium with globally loose credit to an equilibrium with tight credit and shortage of liquidity, causing widespread contraction in economic and financial activities,” they write.

Macroeconomic impacts in the model match up well with the behavior of real-world economies wracked by financial crises. Increasing use of credit before the crisis gradually increases employment, helping to lift the economy. But when credit suddenly tightens, firms are forced to quickly shed workers, causing a marked downturn in economic activity. The longer the period of credit expansion, the harder the fall when lenders’ expectations change. Hence, the sharp drop in employment and GDP in the G7 countries during the last recession, after several years of strong—but perhaps unsustainable—credit growth.

The idea of global economic upheaval resulting from a worldwide shift in expectations has important policy implications, the economists note. If the greatest danger in a financially borderless world is fear of economic distress, then governments can take coordinated action to restore calm by, for example, providing financial markets with liquidity to support asset prices.