The New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC) Program provides tax credits to individuals or corporations that invest in job creation or material improvements in low-income communities, including Native American communities. A close look at Native communities’ use of the NMTC reveals that some have success in attracting NMTC investments, despite unique challenges involved in implementing the program in Indian Country.1/

Costs and complexities

The NMTC Program was enacted by Congress as part of the Community Renewal Tax Relief Act of 2000 and is administered by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund. Through a competitive application process, the CDFI Fund allocates NMTCs to intermediary vehicles called Community Development Entities, or CDEs. A CDE is a domestic, nonprofit, or for-profit corporation or partnership with a primary mission of serving low- and moderate-income persons or communities. To qualify to receive NMTCs, investors must channel their investments into CDEs. The CDEs, in turn, are required to direct substantially all of the proceeds to Qualified Low-Income Community Investments, including investments in Qualified Active Low-Income Community Businesses (QALICBs). The investors then claim NMTCs over a seven-year period. The total credit for each investor equals 39 percent of the original investment.

The program is governed by a web of rules that can be costly and complex for any entity to navigate and that may deter some small, minority-owned CDEs, including Native CDEs, from applying for allocation authority. After spending substantial amounts of money to apply for and obtain allocations, CDEs need to set up an investment infrastructure and monitor program compliance. To facilitate the process, CDEs may need a great deal of consultation with accountants and attorneys, and the resulting fees, added to a reduction in the price that the investor pays for the right to claim the tax credit, can reduce the amount of capital left in the project after the seven-year period by 35 to 50 percent.2/

Additional challenges in Indian Country

Parties involved in structuring an NMTC deal in Indian Country should understand that they might face additional challenges. One example is the difficulty of involving tribal corporations in NMTC transactions. The Internal Revenue Service has ruled that a tribal corporation owned by a Native American tribe shares the same tax status as its parent tribe and, as such, is not a separate entity.3/ Consequently, some in the field conclude that tribally owned corporations may not be considered corporations for NMTC purposes and thus cannot be considered QALICBs.

Another challenge stems from the interpretation of a Treasury regulation that prohibits NMTC-funded properties from being used for gambling, among other purposes. Depending on how the regulation is interpreted, community development practitioners might conclude that if a tribe that owns and operates a casino leases office space in an NMTC-funded building, the arrangement might taint the NMTC transaction.

Then there are the long-standing barriers to lending that reservation residents face. For instance, the complexities of land ownership in Indian Country make it difficult to use reservation lands as mortgage collateral.4/ Also, on many reservations, commercial codes governing business lending are absent or insufficient, leaving financial institutions with uncertain recourse in the event of a loan default.5/

Small numbers, significant benefits

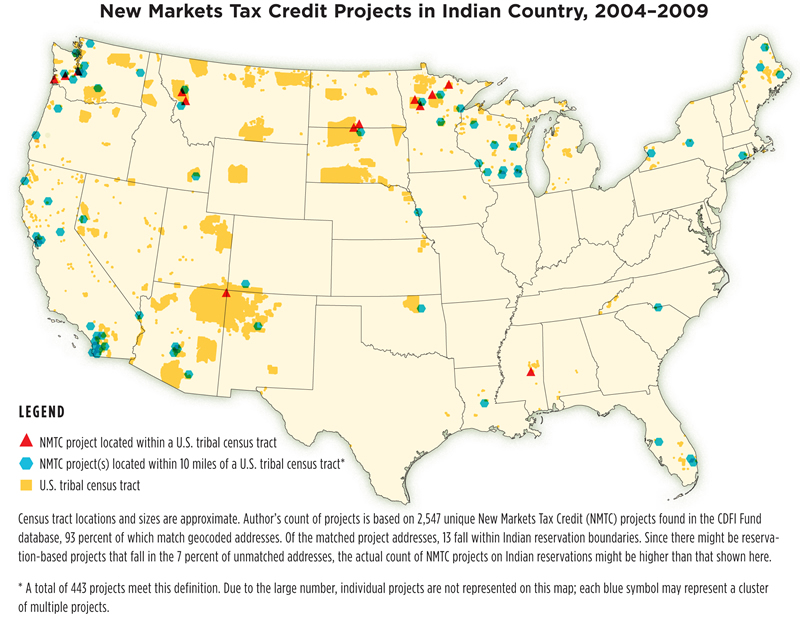

Despite the challenges, some applicants have succeeded in deploying NMTC investments in Indian Country. Since its first round of allocations in 2002, the NMTC Program has made 594 awards totaling $29.5 billion in allocation authority. Out of the 594, 18 awards totaling $977 million in allocations have gone to organizations that plan to invest some or all of the funds in rural reservations or highly distressed urban communities with significant Native American populations. As of 2009, CDEs reported making about $15.8 billion in NMTC investments to about 2,900 projects located in all 50 states. American Indian reservations received about $62 million of these NMTC investments, or 0.39 percent of the total. (To view the distribution of NMTC qualified investments and projects on or near Indian reservations in the contiguous 48 states, see the map below. The map shows projects from the CDFI Fund’s NMTC database that match geocoded addresses on or in close proximity to reservations.)

Click on graph to view larger image

While the share of NMTC investments in Native communities is relatively small, the benefits of the much-needed funds can be significant. For example, Travois New Markets LLC (www.travois.com), a Native economic development financing organization in Kansas City, used an NMTC allocation to help the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority build electrical substations in the towns of Shiprock and Cudeii, N.M. The project enabled the Navajo Nation to double its electrical capacity in the Shiprock and Cudeii areas to support economic development efforts. According to Phil Glynn, vice president of economic development at Travois, “This investment is a remarkable example of how the NMTC Program can be used to address infrastructure issues in Native communities.”

Ninth District Insights

Several CDEs in our own Federal Reserve District have attracted NMTC investments for Native-led projects and have insights to share about making the projects work. For example, Minneapolis-based Community Reinvestment Fund, USA (CRF, www.crfusa.com) used NMTC financing to fund a Native-owned pharmacy and retail store on the Flathead Reservation in Montana. The project created two jobs, bringing the pharmacy’s total number of employees to ten, in a community where the unemployment rate at the time was 30 percent above the national average. According to Warren McLean, CRF’s vice president of development, the organization partnered with the Missoula Area Economic Development Corporation to close and fund the project.

“This was a good business strategy for us because it allowed the local organization to take advantage of the NMTC program without applying for an allocation. It also allowed them to bring their Indian Country economic development expertise to the table to smooth out any compliance-related issues,” McLean says.

Another allocatee in our district, Midwest Minnesota Community Development Corporation (MMCDC, www.mmcdc.com) in Detroit Lakes, Minn., provided low-cost financing through the NMTC program for the White Earth tribe’s Oshki Manidoo Center, a healing center for at-risk Native American youths. This $8.2 million project involved the purchase and renovation of a 40-acre facility in Bemidji, Minn. Julia Nelmark, NMTC program director for MMCDC, credits the successful closing of the allocation to the relationship MMCDC and the White Earth tribe established.

“The federal tax laws are complex, but the parties involved in an NMTC transaction can understand and deal with them. What’s really important is for tribal members to get comfortable with the practitioner. It boils down to trust and patience to successfully fund and close transactions such as this one in Native communities.”

More to come?

In June 2011, the CDFI Fund announced the availability of $3.5 billion for the 2011 tax credit allocation round of the NMTC Program. How much of that total will be invested in Indian Country remains to be seen. Thanks to a small but determined group of development organizations and tribes, including those mentioned here, entities that are interested in using the NMTC program to benefit Native communities have some good examples to follow.

Michou Kokodoko is a senior project manager in the Minneapolis Fed’s Community Development Department.

1/ “Indian Country” refers to all self-governing tribal lands in the United States, including American Indian reservations, dependent Indian communities, and Indian allotments, whether restricted or held in trust by the federal government. See 18 U.S.C. §1151(a)–(c).

2/ New Markets Tax Credit: The Credit Helps Fund a Variety of Projects in Low-Income Communities, But Could Be Simplified, Government Accountability Office Report 10-334, January 2010, page 21.

3/ See Revenue Ruling 94-16, March 21, 1994. Available at www.irs.gov.

4/ There are multiple ways land ownership is structured in Indian Country, including tribal trust, tribal fee, allotted trust held by individual Indians, and fee held by non-Indians.

5/ For more on this, see “A super model: New secured transaction code offers legal uniformity, economic promise for Indian Country,” Community Dividend, Issue 1, 2006.

For more informationDetails about the New Markets Tax Credit Program and application process are available via the “What We Do … Programs” tab at www.cdfifund.gov. |

Michou Kokodoko is a senior policy analyst in the Minneapolis Fed’s Community Development and Engagement department. He leads the Bank’s efforts to promote effective community-bank partnerships by increasing awareness of community development trends and investment opportunities, especially those related to the Community Reinvestment Act.