Montana’s Flathead Valley attracts well-heeled tourists, vacationers and retirees from around the country. Tony enclaves of log homes dot the outskirts of Kalispell, a city of 20,000 that is a gateway to Glacier National Park. But not everybody in the valley is wealthy; many people can’t afford regular medical care at a private doctor’s office. For years, those residents have forgone care or ended up in a hospital emergency room when struck by accident or serious illness. Since 2008, such patients have had someplace else to go when they get sick: a clinic in Kalispell that treats everybody, regardless of ability to pay.

The Flathead Community Health Center provides basic medical services such as physical exams, X-rays, immunizations and tooth fillings. Sixty percent of the clinic’s patients have incomes below the federal poverty level, and 70 percent have no health insurance. Such patients pay fees on a sliding scale calibrated to family size and income. Minimum fees are $10 for a medical visit, $20 for a dental appointment.

A medical underclass—low-wage workers in hotels, restaurants and other seasonal, tourism-oriented businesses—has long existed in the region. But economic hardship over the past two years has increased the need for the center, said Executive Director Wendy Doely. “[Flathead County] has suffered a lot during the economic downturn,” she said, noting that the county had the third-highest unemployment rate in the state in July because of layoffs in the lumber, construction and service industries. Along with their jobs, many clinic patients have lost their health insurance coverage.

The opening of Kalispell’s community health center is part of a dramatic expansion of CHCs nationwide and in the Ninth District during this decade. Formally called federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), these nonprofit clinics provide primary care for underserved populations—people with little or no health insurance, or limited access to medical care.

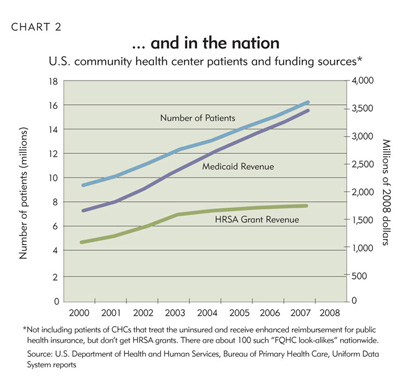

Supported by federal grants and state money—some of it in the form of increased funding for public health insurance programs—the number of patients treated nationwide at CHCs increased 65 percent between 2000 and 2007, to over 16 million annually. Federal government figures show that the community health network has grown at an even faster pace in the district, both in patients served and territory covered. In Minnesota, Wisconsin, Montana and the Dakotas, the number of patients seen by health centers each year nearly doubled between 2000 and 2008. Including the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, 22 new CHC organizations have formed in the district in this decade—an increase of 60 percent.

Many community health centers are located in low-income neighborhoods in cities such as Minneapolis, Fargo, N.D., and Billings, Mont. But they’ve also taken root in much smaller communities—Cook, Minn.; Faith, S.D.; Iron River, Wis. A number of CHC organizations have expanded their operations over the past 10 years, opening satellite clinics in surrounding towns and adding services such as dental care, on-site drug prescriptions and mental health counseling. Some health centers specialize in treating migrant workers, at-risk schoolchildren or the homeless.

This year, health centers got a shot in the arm from federal economic stimulus funding aimed at strengthening a health care system safety net frayed by economic troubles. (The Flathead CHC received $1.5 million in stimulus grants last spring.) Legislation enacted by Congress last year and several health care bills generating intense debate at the Capitol this fall call for further national expansion of CHCs, although a federal budget deficit and opposition to a major overhaul of health care may derail those plans.

Community health centers have garnered staunch government support because they’re seen as cost-effective providers of health care. They operate on a different model than the one followed by most private medical practices, focusing on basic, everyday care by teams of doctors who earn salaries, not fees for each service performed. By providing preventive care to patients who would otherwise receive less care or forgo it altogether, CHCs aim to keep them healthier, potentially avoiding expensive medical bills down the road.

“By having a health center, you catch people with medical problems in the early stages,” said Dr. Jon Berg, medical director of Valley Community Health Centers, a trio of clinics in northeastern North Dakota. “You treat them, and they avoid going to the emergency room.”

Policymakers desperately want to find a way to improve access to health care while curbing its increasing costs. The growing number of people receiving care from CHCs shows that they do improve access, at least for a segment of society that has little recourse under the current system. But ongoing research on treatment costs has yet to prove that further expansion of health centers in the district would reduce the overall cost of health care.

Clinics of last resort

The tug-of-war in Congress over reshaping the nation’s health care system has highlighted the fact that many people either can’t afford or don’t have ready access to medical care. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that 46 million people in the United States lacked health insurance in 2008—about 15 percent of the population. (In district states, the proportion of uninsured ranged from 8.5 percent in Minnesota to 16 percent in Montana.)

Those figures don’t count people with public health insurance, such as Medicaid or Medicare, who have difficulty getting treatment because of the federal government’s relatively low reimbursement rates for those programs. And in some rural areas, even those with private insurance may not have easy access to health care, because of local shortages of primary care physicians and dentists. Berg and one other doctor at Valley Community are the only physicians practicing in the small towns of Northwood and Larimore, N.D.

It was this unmet need for basic health care that President George W. Bush addressed by pushing for a major expansion of community health centers, created in the 1960s to improve medical care in inner cities. During the Bush administration, Congress doubled federal funding for health centers to more than $2 billion a year, leading to a rapid increase in the number of clinics and patients served.

To qualify for grants from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), health centers must show that they’re meeting an unsatisfied local need for primary care. They must also operate as nonprofits and accept all patients, charging on a sliding fee scale for those at or below 200 percent of federal poverty guidelines.

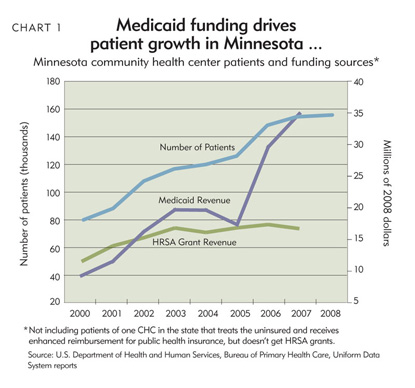

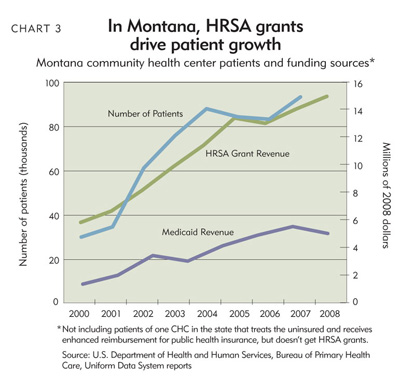

Nationally and in the district, the number of patients treated by CHCs has risen in tandem with revenue increases from HRSA dollars and Medicaid, which provides health care coverage for the poor. But district states differ in the degree to which these respective sources of funding have driven growth in health center capacity (see Charts 1 and 2).

Montana and the Dakotas have seen big increases in Section 330 grants in this decade, according to data tracked by HRSA’s Bureau of Primary Health Care. In Montana, HRSA funding surged from $5 million in 2000 to about $15 million seven years later. During that time, the number of HRSA grantees in the state increased from seven to 15, and the number of patients seen annually more than doubled to almost 85,000 (see Chart 3).

New clinics such as the Flathead center were sorely needed even before the recession, noted Mary Beth Frideres, deputy director of the Montana Primary Care Association in Helena, an organization that promotes CHC development. The state has historically had a large proportion of low-income residents as well as a big helping of uninsured. The Census estimated in 2004 that over a third of Montanans had incomes under twice the federal poverty level, the target population for CHCs.

Said Frideres: “The people who don’t have insurance, the people who make little money—they’re the ones who are going to come to a place where they’re not going to get a huge bill and be unable to pay it. That’s what community health centers are about.”

In 2000, North Dakota had just one health center, in Fargo; $17 million in grants since then has helped launch five CHC organizations and 47 clinics serving about 26,000 patients. However, between 2004 and 2008, inflation-adjusted HRSA funding in the state and in South Dakota declined because many communities have had trouble qualifying for new health centers and satellites in the face of fierce national competition for federal funding.

In Minnesota and Wisconsin, patient growth has had more to do with increasing Medicaid revenue at established centers than HRSA grants for new clinics. These states have gained proportionately fewer new delivery sites than Montana and the Dakotas because their demographics—relatively high incomes and rates of insurance coverage—handicap communities in the national competition for startup grants. Since 2000, Wisconsin has gained only three HRSA grantees, for a total of 16.

But CHCs in Minnesota and Wisconsin have drawn large numbers of low-income patients enrolled in Medicaid and state health insurance programs. Health centers are disposed to accept patients enrolled in these public plans because the government—recognizing the financial strains under which CHCs operate—reimburses them for treatment at a higher rate than private clinics and physicians receive. (Medicare services for seniors and the disabled are also reimbursed at a higher rate.)

Relatively high income ceilings for Medicaid coverage in Minnesota and Wisconsin make it easier for residents to qualify for the federal/state program—avoiding paying for care out of their own pockets—than those of other states with stricter requirements. In Minnesota, CHC patient revenue from Medicaid has increased at a much faster pace than HRSA grant funding. Between 2000 and 2007, Section 330 funding increased 46 percent, adjusted for inflation. During the same period, Medicaid funding almost quadrupled in real dollars.

In addition, expanded eligibility in the past five years for state health insurance programs—MinnesotaCare in Minnesota, BadgerCare in Wisconsin—has encouraged more low-income adults to get treatment at CHCs.

Just the basics, doc

Health centers have attracted billions of dollars in government funding over the years because they’re widely viewed as effective health care providers that save the health care system billions more in the long run. The National Association of Community Health Centers and other proponents claim that CHCs more than recoup their operating costs by efficiently delivering primary care to people who would otherwise do without.

Health centers have attracted billions of dollars in government funding over the years because they’re widely viewed as effective health care providers that save the health care system billions more in the long run.

Certainly the health center model seems promising as a way to reduce overall health care expenditures. A number of studies have shown that health centers provide primary care that is typically as good and in some cases superior to that provided by private doctors’ offices and clinics. Little reliable data exist on comparative costs of care—whether CHCs achieve the same health outcomes for less money than private primary providers. But efficiency is inherent in the health center model, which emphasizes basic care by salaried doctors and nurses who often collaborate on diagnosis and treatment.

Typically, private practitioners earn fees for each service performed—an MRI, a hip replacement, a root canal. This fee-for-service system fosters a powerful incentive for medical providers to perform more treatments and tests—a major driver of escalating health care costs. “You get what you pay for,” said Berg of Valley Community Health Centers. “If you’re paying for more tests and procedures, that’s what you’ll get.”

Putting health center providers on salary eliminates this incentive. At Valley Community, doctors earn productivity incentives, but the extra pay—up to 5 percent of annual salary—is for seeing more patients, not carrying out more procedures, Berg said.

Ironclad protection against litigious patients also reduces the urge for doctors to order tests of questionable value, just in case. Health center staff enjoy the same immunity from malpractice lawsuits as federal employees; the U.S. government acts as their primary insurer. Liability protection also saves CHCs millions of dollars a year in private insurance premiums. (The downside of such protection is that it may result in less than the optimum amount of testing, harming patients and increasing legal costs.)

Advocates of health centers say that they achieve their greatest health care cost savings by treating the medical problems of underserved populations before they become more serious—and expensive. It’s well established that timely preventive care reduces costly trips to hospitals and emergency rooms (the costliest form of care in the health system) by patients suffering from chronic maladies such as heart disease, diabetes and asthma. In the case of low-income or geographically isolated patients, CHCs often provide the only means of such vital intervention, said Dr. Ann O’Malley, a senior health researcher at the Center for Studying Health System Change, a health care think tank based in Washington, D.C.

“Community health centers are very good at providing access to patients, and we know that good access to primary care helps avoid certain types of hospitalizations for certain types of conditions,” she said.

However, empirical studies that purport to show the salutary influence of health centers on “downstream” illness and medical costs are tricky to interpret. For example, in studies that found that health center patients incur lower total health care costs (including treatment at hospitals and drug prescriptions) than non-CHC users, it’s unclear whether the savings are due to better preventive care or simply more limited care.

A forthcoming research brief by the Robert Graham Center, a primary care research group affiliated with the American Academy of Family Physicians, found that average annual medical spending for patients who rely on CHCs for most of their care was 12 percent lower than for people who are seen mostly by private primary care doctors. But there’s a crucial difference between the two patient groups: If you’re a CHC patient with no private insurance, you’re going to have a hard time getting referred to a specialist outside the clinic for a complex or life-threatening condition.

If health center patients had equal access to the expensive services of surgeons, cardiologists and other specialists, their total medical costs could equal or exceed those of the private primary care patients.

Also, comparative cost studies don’t capture the full costs of health center care, which include HRSA grants to pay for treatment of the uninsured and malpractice jury awards or settlements paid by federal taxpayers on behalf of CHC practitioners. The real cost to society of health center care may be higher—or lower—than estimates based on average household medical expenditures.

Carry that weight

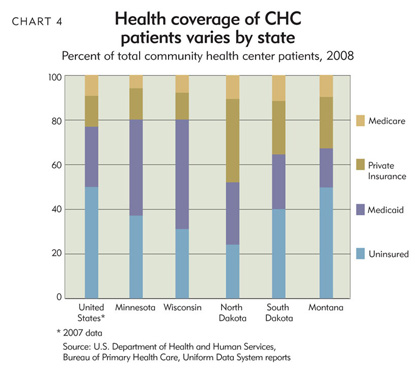

Health centers’ mandate to treat all patients is a heavy burden, because revenues often fail to cover the cost of caring for the uninsured. A large proportion of CHC patients have no health coverage of any kind, public or private. In Minnesota, 37 percent of health center patients had no health insurance last year, according to HRSA data. In Montana, more than half of CHC patients had no coverage in 2008 (see Chart 4). Those figures are even higher at clinics in low-income urban neighborhoods or on American Indian reservations.

Some CHC patients have private insurance, but it affords little protection against sickness and mishap. In North Dakota, for example, many farmers and small-business owners carry insurance deductibles of $5,000 or more, said Scot Graff, CEO of the Community Health Care Association of the Dakotas. “It’s not health insurance; it’s catastrophic, save-the-farm insurance,” he said. “Functionally, they’re uninsured for primary care.”

Federal grants are supposed to cover the cost of treating the uninsured, but a clinic’s Section 330 funding doesn’t necessarily increase when more uninsured patients come in the door. Funds to expand service capacity at existing health centers are hard to come by.

In Minnesota, the costs of treating uninsured patients have outstripped increases in HRSA funding for years, according to data compiled by the Minnesota Association of Community Health Centers. Last year CHCs in the state spent $32 million caring for the uninsured, but received only $17 million in HRSA grants. Sliding scale fees don’t make up the difference; the portion of costs covered by patient fees has dropped by half since 2001.

Patients covered by comprehensive private insurance subsidize the uninsured—a practice called cost shifting. But the chunk of CHC patients with private insurance is fairly small—about 22 percent in Montana, 13 percent in Wisconsin. And patients with solid health plans are even scarcer at clinics serving large numbers of poor or minority patients. West Side Community Health Services, a CHC with 18 sites in Minnesota, was forced to close a clinic in south Minneapolis three years ago when the number of uninsured patients became overwhelming. “We can sustain a significant percentage of uninsured, but that’s not unlimited,” said Terry Hart, interim executive director of the health center.

To fill budget gaps, CHCs depend on state and local government grants, and charitable contributions from foundations and corporations. Health centers throughout the district have benefited from nonfederal support, but such funding varies from state to state. For example, Minnesota CHCs received $18 million in state and local government funding in 2007—slightly more than they received in HRSA grants. In contrast, CHCs in North Dakota gleaned only $25,000 from that source—a tiny fraction of over $3 million in Section 330 funding received that year.

The national recession has further strained the resources of CHCs. A number of health centers in the district have reported increased traffic over the past year as people who were once covered by employer-sponsored health insurance search for other medical options. “There’s a lot of pressure being put on all parts of the health care system right now,” said Stephanie Harrison, executive director of the Wisconsin Primary Health Care Association. “You see people who are using [hospital] emergency departments, you see people who are using health centers more vigorously, and a lot of that is because these folks have lost their jobs.”

Harrison—and several other sources at CHC organizations—said that demand is especially high for dental services, because many low-income people lack dental insurance and few private dentists accept Medicaid or state insurance plans. Moreover, dentists are thin on the ground in rural areas of the district such as northwestern Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula and eastern Montana.

Earlier this year, besieged health centers got some relief from economic stimulus funding. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) authorized $2 billion to pay not only for new health centers but also for expanded services and facility upgrades at existing clinics. In addition to a long-sought $1.3 million grant to cover uninsured patients, the Flathead CHC received $241,000 in capital improvement funding. Doely said that the clinic plans to spend the money on medical and dental equipment, an electronic records system and upgrades to phone systems, signage and building security.

Horizon Health Care, a CHC serving 10 small communities spread across South Dakota, was awarded $1.1 million in ARRA funding to buy new X-ray equipment, expand its telemedicine capability and hire extra staff, including a full-time family nurse practitioner.

Rx for rising costs?

Another wave of health center expansion may sweep across the nation and the district under enacted or proposed federal legislation. In reauthorizing the CHC program last year, Congress called for a 60 percent increase in funding through 2012. And this fall, amid a vigorous debate over revamping the health care system, lawmakers envisioned a greater role for health centers. An early version of one House bill would create dedicated funding for CHCs and boost nationwide HRSA funding to more than $8 billion annually over the next 10 years.

Other proposals being considered as part of health care reform would expand Medicaid eligibility and subsidize the cost of private insurance, encouraging more low-income people to come into health centers (or seek care at private doctors’ offices and clinics).

Health center advocates in the district are optimistic that the political winds are blowing in their direction. “The community health care model is cost-effective, quality primary care,” said Frideres of the Montana Primary Care Association. “You can’t beat it. So I think there’s going to be even more need for community health centers.” Graff speculated that increased funding for CHCs might help mid-sized cities in the Dakotas such as Minot and Aberdeen secure HRSA grants to open health centers.

But prospects for more health centers and satellites depend on appropriations from Congress to fund CHC initiatives, and at the moment money is tight in Washington. For the 2010 fiscal year, the Obama administration has proposed no funding increases for health centers.

Supporters of health centers as part of the solution to rising health care costs point to estimates of how much money would be saved under proposed health care legislation. A recent study by researchers at The George Washington University calculated that under one health care reform scenario, doubling CHC capacity would save the U.S. health care system $37 billion annually by 2019.

That impressive figure is questionable, because it uses the same methodology as the Robert Graham Center study, extrapolating from average figures on lower total cost of care for CHC patients. If health care system legislation extended private health insurance coverage to low-income health center patients, they might use more specialist care, raising the treatment costs of CHC users.

But the study’s conclusion that investing in community health centers can “bend the curve” of future health expenditures raises the question of how much money might be saved if more people—those with well-paying jobs and private insurance in addition to the medically underserved—went to CHCs for their basic medical needs.

Broadening the health center model to cover the general population appears unlikely in the near term. Current and proposed health center legislation focuses on catching people who slip through the cracks of the health care system, not extending public medicine to the middle class. But it might make sense to take certain elements of the CHC approach, such as salaried doctors and collaborative care, and apply them to other health care settings.

“There are certainly lessons that the rest of the health care system can learn from community health centers in terms of their organization, their facility in dealing with a vulnerable, low-income population, their use of teams,” said O’Malley of the Center for Studying Health System Change.

She noted that some private health organizations such as Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and Kaiser Permanente, a managed care organization in California, already employ salaried physicians and take a team approach to diagnosis and treatment. Not coincidentally, these institutions are also leaders in keeping a lid on health costs; Mayo’s Medicare spending per patient is among the lowest in the country.

Community health centers use the term “medical home” to describe their hands-on, one-stop-shopping treatment model. Berg, an unabashed champion of CHCs, sees that approach as one way to maintain quality of care while curbing seemingly inexorable increases in health care costs. “The patient-centered medical home—that whole idea is the thrust we want to achieve, and it’s an idea that would well play across the country,” he said.