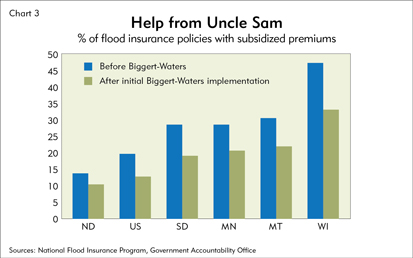

Big changes are afoot, thanks to federal Biggert-Waters legislation passed in 2012 and a federal effort to update and remap flood-prone areas. Subsidies for high-risk properties are being phased out, and flood zone remapping will require some households to buy insurance where it was previously optional. Though the number of flood insurance policies is comparatively small in the Ninth District, the shift to full-rate premiums will eventually hit policyholders here relatively hard because district states have a high percentage of subsidized policies.

Big-ticket household purchases and other financial decisions often come with a lot of cost-benefit questions. Do we need it? Can we afford it? Can we afford not to have it?

When it comes to the purchase of flood insurance, a different question comes to the fore: Do we feel lucky?

Despite the fact that floods are by far the most common and costly natural disaster, many households and firms—even those in high-risk areas—don’t carry flood insurance. The reasons vary, but many choose not to carry flood insurance for the simple reason that they believe they can do without, being lucky enough to avoid spring floods from winter’s melt or flash floods from torrential rain.

Most years the strategy works well, and households can save an average of $500 to $1,000 annually. But floods are predictably unpredictable: While they are hard to forecast in any given year, historical data show again and again that they will occur, eventually, in many places. And when they do, they are often devastating for people and communities.

There’s no better example in the Ninth District than Minot, N.D. After a major flood hit the city in 1969, flood dikes were built to ward off a similar engorgement of the Souris River, which snakes through the heart of town. Then, in June 2011, the mother of modern floods poured into town, swamping previous river crest levels and the flood barriers meant to protect the city, which remained flooded for much of the summer. More than 4,000 homes and businesses were damaged, many catastrophically. Fewer than 10 percent of structures carried flood insurance.

The historic flood did not come without warning. Residents were alerted to possible serious flooding in late spring, when major precipitation fell in the Canadian watershed that feeds the Souris, “but a lot of people believed it wouldn’t affect them,” said Lynn Klein, an agent with First Western Insurance of Minot. While the agency took numerous phone queries about flood insurance before the flood hit, Klein estimates that only about one in eight followed through and bought a flood policy.

“We can’t get people convinced that flood insurance is very, very important. ... There’s not enough education out there,” said Klein. “[People] are so afraid of [the cost], they don’t want to listen.” This despite the fact that flood insurance is a government-operated market and has long been subsidized for high-risk areas to encourage more people to protect their properties.

But in Minot and across the Ninth District, homeowners living anywhere near water would be wise to start paying more attention because flood insurance subsidies are being phased out, thanks to federal legislation passed in 2012 and a federal effort to update and remap flood-prone areas.

Some flood insurance is purchased voluntarily. But many in high-risk areas are required to have it, and when the subsidies end, these policyholders will see premiums rise substantially, bringing the cost of insurance more in line with the actuarial risk to property exposed to floods. As a result of an ongoing federal initiative to remap flood plains, some property owners are finding out not only that they have to start buying flood insurance, but at much higher, unsubsidized rates.

Though the number of flood insurance policies is comparatively small in the Ninth District, the shift to full-rate premiums will hit policyholders here relatively hard because district states have a high percentage of subsidized policies. Price hikes also will force some households and businesses to reevaluate the costs and benefits of living close to water, and will convince some who purchase insurance voluntarily to jettison their coverage, creating a shallower risk pool and potentially undermining the insurance program.

Flood policy 101

Roughly 90 percent of all natural disaster events involve some flooding, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and these events cause more damage in the United States than any other severe weather event. Estimates vary, but the average homeowner is several times more likely to experience loss from flood than from fire during the course of a 30-year mortgage; for those located in flood-prone areas, the risk ratio skews even higher.

Because of the high incidence and costly damage associated with floods, private insurance carriers historically have deemed the threat of flood uninsurable, or insurable only at great cost. Most home and business owners simply did without. But as more development migrated to the amenities of coastal, river and lake shorelines, U.S. taxpayers faced increasing costs when flooding hit properties ill prepared to absorb the financial damage.

So in 1968, Congress created the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) to provide—and in some cases, require—flood insurance for structures in or near flood zones. Today, property owners are required to purchase flood insurance if they have a federally backed loan or mortgage and structures are located within a so-called special flood hazard area, which has a 1 percent annual chance of flood (also called the 100-year flood plain). Those outside special flood hazard areas can purchase insurance voluntarily.

Flood insurance policies are sold by private property and casualty insurance firms on behalf of the NFIP. Premium rates vary depending on a structure’s proximity to flood-risk zones and other factors (like a structure’s age), with insurers receiving fees for acting as the go-between. Average annual premiums run about $500 for preferred-rate policies and about $1,000 for standard-rate policies (though the premium itself does not necessarily indicate flood exposure; more on this later).

Much like homeowners insurance, flood insurance policies are in force for one year and have a 30-day waiting period before coverage becomes effective, a modest attempt to dissuade homeowners from waiting until the last minute to buy flood insurance. To encourage owners in high-risk areas to purchase flood insurance, the NFIP charges artificially low premiums for about 20 percent of policies nationwide.

The NFIP currently covers approximately 5.6 million households and businesses across the country and about 54,000 in the Ninth District. The penetration rate of flood insurance is hard to calculate exactly, because policies insure residential and business structures for which there are no hard counts. But for context, there are more than 4 million single-family and mobile homes in Ninth District states.

Logically, penetration rates are higher in and near flood zones. Ceil Strauss is the state flood plain manager at the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR). She estimated that insurance levels among all structures in flood plains likely ranged between 10 percent and 20 percent at the community level, with the large majority purchasing it because they are required to do so by virtue of having federally backed mortgages. This involves any mortgage from a financial institution that is supervised or insured by federal agencies like the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. or originated through or backed by federal agencies like the U.S. Department of Veterans Affair or Federal Housing Administration or purchased in the secondary market by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac.

“There are not very many that get it voluntarily, except maybe for a few that have memory of past [floods],” said Strauss. While the percentage of voluntary flood policies is low, their overall numbers are considerable. Districtwide, there are more policies outside high-risk areas for the simple reason that high-risk flood zones are geographically small and most people live in safer areas.

Cloudy, with a 50 percent chance of ruin

It’s common practice to hold off buying flood insurance until there’s evidence of a potential flood. The historic floods of 2011, which affected much of Montana, the Dakotas and portions of western Minnesota, offer a good illustration of this practice.

In December 2010, there were 52,500 flood insurance policies in district states. Over the coming months, heavy winter and spring precipitation prompted forecasts of widespread flooding by local meteorologists and the U.S. Geological Survey—forecasts that proved not only correct, but possibly understated.

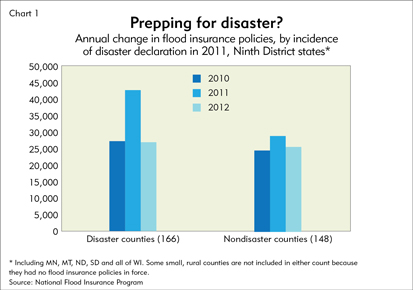

By December 2011, the number of policies in force had jumped by slightly more than 20,000—or nearly 40 percent. The increase was almost entirely among voluntary buyers living in counties declared a flood disaster sometime during that year (see Chart 1).

The following year, shortly after some of the most damaging floods in decades, the number of policies in these same disaster counties actually fell 1 percent below 2010 levels—symptomatic of a mentality that floods, like lightning, won’t strike twice in the same place. In contrast, flood policies in district counties not declared flood disasters in 2011 saw considerably less volatility from 2010 to 2012. (See sidebar for a breakdown of flood policies in Ninth District states.)

Better precipitation forecasts and analytical tools for predicting flood crests have made this wait-and-see strategy for buying flood insurance somewhat more reliable than in the past. Flood policies in 2011 rose because heavy snowpack and high moisture content were “widely advertised” leading into the spring, according to Strauss.

She added that “some people can benefit” from buying insurance in this manner, but “more and more flooding comes from events you can’t predict ahead of time”—like the torrential rains and flash floods in the Boulder, Colo., region in September 2013 and in Austin, Texas, more recently. Property owners there had little warning of the coming deluge.

Bailing out

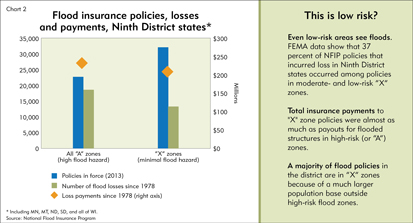

Does it matter that people don’t buy flood insurance? Certainly not when rivers and streams stay within their banks. But when floods inevitably strike, insurance provides a financial security blanket. Since 1978, the NFIP has paid policyholders more than $500 million for flood claims (see additional policy information in Chart 2).

But given the regularity of floods in some district states, that blanket is perilously thin. Since 1970, according to FEMA, there have been more than 120 declared disasters in five district states involving some degree of flooding (many also include other events like severe storms); Minnesota has averaged close to one flood disaster per year over this period.

And it’s not just those directly affected who get a soaking when flood losses are uninsured. Since 1978, for example, the NFIP has paid out $256 million to flood policy holders in North Dakota—easily the most among Ninth District states. But that figure is minuscule compared with uninsured losses and disaster assistance provided by the federal government in repeated floods. From the 2011 flood alone, uninsured costs to government, private residents and business owners easily surpassed lifetime NFIP-insured losses. That year, almost 7,500 households in North Dakota received $96 million in direct grant assistance from FEMA (by definition, they were uninsured). FEMA spent another $93 million on other housing assistance, including bringing in 2,200 trailers to shelter those displaced from their homes in Minot.

While it’s easy to support helping people in need, emergency assistance from FEMA and other government agencies ultimately discourages the use of flood insurance because it introduces what economists call moral hazard—the tendency of people to take risks because they don’t bear the full consequences of their actions.

“The people that did the right thing [by buying flood insurance] are not getting rewarded,” said Strauss, with the Minnesota DNR. Instead, people with flood insurance “are seeing their neighbor [without insurance] get bailed out. That kind of assistance that rewards bad decision-making is a problem.”

Emergency flood aid to uninsured households is not particularly generous. For those hardest hit in South Dakota during the 2011 floods, roughly 1,200 households received an average of just $4,000 in grant aid, according to FEMA records. Average grant aid was higher in North Dakota because of the devastation in Minot, but still averaged just $13,000—a small fraction of the damage sustained by most households. In Minot, 4,100 structures were inundated, about 80 percent of which saw at least six feet of water on their main floor. The NFIP estimates that the average damage from four feet of water is $75,000.

But such details are not widely understood. Disaster news coverage often focuses on government recovery assistance, with congressional leaders passing additional aid packages in the hundreds of millions, even billions, of dollars for natural calamities such as hurricanes Sandy and Katrina. Failing to respond to a disaster spells political calamity for elected and appointed government officials. But low subscription to flood insurance programs suggests that responding with aid undermines a program specifically designed to cover losses from floods, and at much more comprehensive levels.

The NFIP has tried to persuade more consumers to buy flood insurance by subsidizing premiums for those in flood-prone areas. But that has consequences of its own. While it has increased participation, it offers another helping of moral hazard, because premiums charged don’t reflect the real, actuarial risk of living in flood-prone areas. As a result, artificially cheap insurance has encouraged households and businesses to build or expand in areas where they historically had not (because of the high potential for personal financial loss) and transferred much of the financial risk to taxpayers.

This strategy worked for a while. Until 2003, the NFIP did a reasonably decent job of balancing the annual ledger of profits and losses despite the subsidies. But since then, major catastrophes—most of them coastal hurricanes—have put the program deeply in the red as more and more development was allowed along the coasts and near other water bodies, driving up damages when disasters hit. Once claims related to Hurricane Sandy are settled, the NFIP expects to have program debt—borrowed from the U.S. Treasury with permission from Congress—of about $28 billion. The program has imposed surcharges on policies to buy down the debt, but it’s not nearly enough given the size of the deficit and the recent frequency of disasters.

The Ninth District isn’t hurricane territory, but it gets its share of subsidies. In fact, the percentage of subsidized policies is higher among most district states than the national average of 20 percent (see Chart 3), in part because many structures located in flood hazard areas were already built (and then grandfathered) when flood plain mapping and management went into effect in the 1970s. Only North Dakota, at 14 percent, has a lower share of subsidized policies among district states, and that is likely because the state has much higher participation overall in flood insurance.

Make them pay

Thanks to these colliding trends—low participation, high subsidies, steep program debt—significant change is afloat for flood insurance, especially for those with subsidized policies. In late 2012, Congress passed the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act in hopes of eliminating the moral hazard of artificially low flood insurance costs and putting the NFIP on a sustainable financial path. It does so by eliminating subsidies for flood insurance and dramatically increasing premiums for policies in high-risk areas to reflect true flood risk.

Biggert-Waters provisions won’t all happen at once, and there are a lot of quirks to the law, so its full effect will likely come in waves—some small, others larger. For example, though passed more than a year ago, the first major changes legislated by Biggert-Waters are just now taking root.

This summer, subsidized rates for nonprimary residences, secondary residences, businesses and repetitive-loss properties were phased out, and subsidies for some other, targeted types of properties were eliminated in October. This will affect roughly 438,000 flood insurance policies, or one-third of all subsidized flood insurance policies nationwide. In the Ninth District, the initial implementation of Biggert-Waters is expected to impact more than 5,000 property owners, or about one-third of the 16,000 subsidized policies in the district, according to data and calculations from the NFIP and the Government Accounting Office.

To help with the financial adjustment for these properties, premiums for existing subsidized policies will be gradually raised, with annual increases capped at 25 percent until rates reflect actuarial risk, which FEMA believes could take more than five years for some properties.

A flood of confusion, controversy

For the remainder of subsidized policyholders, there is both good and potentially terrible news, depending on where they call home.

Those with existing flood policies on their primary residence will continue to pay the same rates—including those with heavily subsidized premiums—until they decide to sell the property or the insurance policy lapses or the property suffers repeated flood losses. But those in high-risk areas where flood policies have lapsed or are being sought for the first time (say, due to the sale of a home) face immediately higher premiums going forward. There is limited grandfathering of rates for some policies, most of which are expected to expire in 2014.

Compounding matters is Section 207 of Biggert-Waters, a controversial element that codifies an ongoing FEMA effort to modernize flood maps by remapping (and digitizing) the nation’s flood plains to more accurately gauge risks. The remapping initiative was started more than a decade ago and subsequently reauthorized and backed with congressional appropriations. Many areas of the country and district are currently undergoing remapping.

That sounds like an important, if mundane, task. But the effort is redrawing the boundaries of many flood zones; consequently, an unknown number of homes and businesses previously believed to be in low-risk areas (with cheaper insurance rates) are being (or will be) recategorized to high-risk zones once remapping efforts are completed.

The combined effect of FEMA remapping and Biggert-Waters means that some home and business owners will be required to buy flood insurance where none was necessary before and forced to pay high, unsubsidized rates to boot.

The changes have caught existing homeowners and prospective home buyers by surprise. In Minnesota, Strauss said that insurance for structures near high-risk zones might see only small increases. Others clearly in the path of future floods with basements and walk-outs more vulnerable to flood damage might see “increases of three, four, five times” their current rate, running into the thousands of dollars, said Strauss.

Steve Marquart, owner of Marquart Insurance Agency of Fargo, N.D., recently fielded a call from a woman looking to buy a house in Grafton, N.D., about two hours north of Fargo. The purchase price of the home was $110,000, and the woman had already put nonrefundable escrow money down on the house. In the past, he said a preferred-risk policy in that region would have cost $458 for $250,000 in coverage. But because the house was in a newly mapped flood zone, Marquart said the policy premium was over $3,000. “She said, ‘I didn’t know that. What am I going to do?’” according to Marquart.

Not surprisingly, higher premiums have created political controversy, especially for home and business owners newly required to buy flood insurance as a result of Section 207. There have been multiple efforts in Congress to delay, scale back or even eliminate portions of Biggert-Waters. The most recent, in mid-November, introduced a bill (the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act) that requires FEMA to complete an affordability study on rate increases—a study expected to take a year or more—and would delay many premium hikes until two years after the study’s completion. As of the deadline for this article, the measure had only been introduced in the House of Representatives and sent to two separate House committees.

Several requests to FEMA for official comment and clarification on a number of issues were not returned, though several FEMA sources responded off the record and for background purposes. FEMA sources acknowledged that remapping has been complicated and delayed by a variety of issues, sowing local confusion about changes to flood risks and subsequent effects on insurance premiums. The mapping effort itself is fraught with sinkholes. Data in some areas are poor and can change when new data sources become available (like from a city or watershed district); funding to keep local remapping projects moving can be inconsistent, and there are frequent local challenges to preliminary flood maps.

The public review process of remapping will now most likely be dragged out even longer because homeowners are learning that the financial implications might be severe, according to a FEMA official, pointing to map updates in Boulder County, Colo., that took almost six years because of continued appeals from people with technical information to dispute the map revisions.

Mapping for major population areas is reportedly done, according to FEMA, but there are still many pockets where mapping still needs to be completed. Marquart, the Fargo insurance agent, said FEMA maps have not yet been completed in some areas of the state, “and I don’t have a good idea of when” they will be made available to agents. Right now, Marquart said he calls a FEMA office in Kalispell, Mont., to get accurate quotes based on the mapping completed to date. Those places that have not yet been mapped are still receiving traditional quotes. Insurance agents know rates are going up, but the “biggest thing would be to get us a map. Then, are we going to stabilize rates?” said Marquart.

According to the Minnesota DNR, as of early fall, roughly half of the state’s counties were still waiting for final maps to be put in force (not including 36 counties where no new map is scheduled due to the lack of significant flood risk). Even areas already remapped have experienced challenges getting the public to understand the changes.

Clay County, Minn., lies across the Red River from Fargo and is home to Moorhead. The county was remapped, effective April 2012, according to Tim Magnusson, county planning director. He said the special flood hazard area (SFHA) “did enlarge somewhat in some areas and shrank in some others. I believe that we did have a net increase of homes in the SFHA, but the exact number has not been determined.” There was also a substantial increase in the size of the 500-year floodplain.

Despite the finality of new maps, Magnusson said “not all owners have been made aware of their [flood-risk] status. We held public meetings and have made it well known that if a party wants to know the flood status of their property, all they need to do is contact the county planning office.” But in some cases, Magnusson said policyholders found out about changes through their mortgage lender within a few months of the maps going into effect, often to tell borrowers they needed flood insurance. “I was very surprised at how quickly mortgage lenders caught on to the new maps,” Magnusson said, adding that some policyholders “will probably see annual rate increases of $800 to $2,000 or more depending on their specific circumstances and elevations.”

Will it hold water?

Short of repealing Biggert-Waters, or portions of it, eventually all subsidies will be eliminated for all policies, but it could take a decade or more, in part because the real estate market is likely to make adjustments on properties with high flood insurance costs as buyers drive a harder bargain for those properties.

Whether this becomes a broader problem for real estate markets, particularly in communities with significant business and residential property in flood plains, is just starting to unfold. Marquart pointed out that the average homeowner’s insurance policy is about $1,000, and flood insurance for some might be three times that amount—an extra monthly payment that could otherwise buy $50,000 to $75,000 more house. “It makes it very difficult to buy a house” in the flood plain, said Marquart.

For many communities, however, the more immediate concern is completing a new flood map. In Minot, insurance agent Klein said the city was scheduled to have new flood plain maps in 2011, but completion was postponed after the devastating flood. “I don’t think maps are done here yet. If it is done now, I’d like to know.” A FEMA website shows that only 22 counties in the state have completed digital maps. Ward County is not one of them.

But even once maps are completed, Klein was skeptical that city residents would change their behavior when it came to the threat of flood. She said she sold a few additional policies this year, but not enough to warrant a trend despite the tangible hardship experienced by many in 2011.

It’s a good illustration of the public’s desire to roll the dice on flood risk, rather than to prepare for and manage that risk. People consistently underestimate the threat of floods and other natural disasters, and government is often too willing to come to the rescue when they occur. While there are understandable reasons for doing so in an immediate sense, both tendencies undermine any ability for insurance to mitigate the financial risk of floods over the long run.

Living next to water “is a choice,” Klein said. She acknowledged that flood insurance “is a unique beast. I’m not sure how any one organization can get a handle on it.” Requiring flood insurance wasn’t the answer, she said. “But if you live closer to water, you need to pay more.”

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.