Clarence Schollmeyer, president and owner of an engineering firm in Kildeer, N.D., had thought about trying to export to Canada for years, but business conditions never seemed quite right. Last September, after attending the AgriTrade trade show in Red Deer, Alberta, Schollmeyer decided to wait no longer to make a move across the border. The Canadian dollar was valued at 89 American cents—a near-record high against U.S. currency—giving Canadian firms a compelling reason to buy Schollmeyer's products, cradles used to transport high-clearance crop sprayers on truck trailers. "[W]ith the stronger Canadian dollar, our products have become very price competitive [in Canada]," he said.

Shortly after returning from AgriTrade, Schollmeyer Engineering landed its first foreign sale, to a Canadian farming concern. Last fall Schollmeyer was planning to attend another agricultural trade show in Manitoba and was putting the finishing touches on a distribution agreement that would give the company access to customers throughout the Prairie Provinces.

A favorable exchange rate has also helped boost prospects of other Ninth District manufacturers looking to export to Canada, and not just in the agricultural equipment sector. Since the Canadian dollar started heading north five years ago, makers of everything from medical instruments to conveyer belts have seen their shipments across the 49th parallel increase. Exports to Canada from the district and individual states have tended to move in lockstep for most of the past decade.

"Since 2004, South Dakota's exports have dramatically increased, largely because of changes in the exchange rate," observed Joop Bollen, executive director of the South Dakota International Business Institute, an organization that promotes state exports.

By expanding the market reach of manufacturers beyond U.S. borders, exports increase revenues and local employment, and attract investment that can fuel additional business growth. So a strong Canadian dollar can contribute to a strong regional economy—at least in sectors that can capitalize on foreign sales. The flip side of a surging loonie is the premium importers pay on Canadian goods.

Weak greenback, strong exports

Canada is the largest U.S. export market, and it accounts for an even bigger chunk of exports from the district—just over $10 billion in goods in 2006, about $1 billion more than five district states shipped to Europe. North Dakota sent almost half of its manufactured exports to Canada, while Montana shipped 42 percent, South Dakota and Wisconsin about 35 percent, and Minnesota 24 percent.

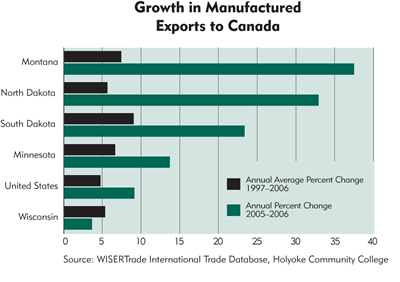

Exports to Canada are not only large; they're getting larger. Since 1997, district manufactured exports to Canada have grown an average 6 percent annually, just slightly slower than growth in manufactured exports to all destinations. From 2005 to 2006, manufactured exports grew much faster than the previous nine-year average in all states except Wisconsin, where exports grew 4 percent. Montana posted the strongest gain at 38 percent (see chart).

The currency exchange rate is just one of many factors that affect trade flows between the district and Canada. Government policies, changes in income levels and demand for goods from other countries also influence trading activity. But it's evident that a waxing Canadian dollar has stimulated export growth by making goods manufactured in the district less expensive for Canadian distributors and consumers.

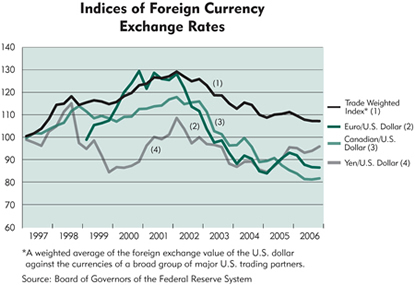

In January 2002, the U.S. dollar was riding high against its Canadian counterpart; a loonie was worth about 62 American cents. Since then, as overseas demand for U.S. dollars has slackened, the greenback has declined in value. In March American tourists entering Canada paid 85 cents for each Canadian dollar, increasing the relative cost of food, lodging and other goods and services. Conversely, Canadians who came south—or bought imported U.S. goods at home—enjoyed greater buying power.

Consumers in other countries have reaped similar rewards as a number of currencies have gained against the dollar. Since 2002, the Japanese yen and the euro have bought more and more U.S. dollars per unit of currency. The Federal Reserve Board of Governors' trade weighted index of a broad group of major U.S. trading partners shows that the U.S. dollar has recently lost value relative to many other currencies (see chart).

"The issue is not so much the strength of the Canadian dollar as it is the weakness of the U.S. dollar," said Skip Taylor, a research specialist in North Dakota State University's Department of Agribusiness and Applied Economics. "The U.S. currency is weak against the yen, the euro and other currencies." Taylor contends that a weak U.S. currency reflects how overseas investors view the U.S. economy.

A weak U.S. dollar punishes importers by increasing the price of foreign goods. Companies in the district that buy Canadian products, such as wheat, petroleum or lumber, must either absorb those extra costs or pass them along to their customers. In contrast, district exporters have made hay as the greenback lost ground against the Canadian dollar. Adjusted for inflation, the value of manufactured goods exported to Canada from five district states since 1997 has tracked the exchange rate fairly closely, taking a definite upturn when the loonie strengthened.

The rising loonie has been a shot in the arm for North Dakota exporters, said Susan Geib, executive director of the North Dakota Trade Office. "A few years ago, when the exchange rate was less favorable, Canadian business almost dried up. Now it's entirely different. Our export volume has increased by about 36 percent over the last few years."

Got plastic, eh?

The pattern of a rising Canadian dollar spurring export growth is particularly noticeable in certain industrial sectors such as plastics and transportation equipment. In the plastics industry, for example, district exports to Canada increased steadily after the U.S. dollar started falling in 2002 (see chart below). In Wisconsin, home to scores of plastics firms, 2006 exports to Canada of food packaging, auto components and other plastic products exceeded 2002 exports at an annual average rate of 9 percent. Districtwide, plastics exports in the same four-year period rose at an annual average rate of 12 percent to $331 million.

Exports of transportation equipment such as Schollmeyer's cradles have hewed very closely to the prevailing exchange rate over the past nine years, continuing to rise as the U.S. dollar wanes. The five district states shipped about $2.3 billion in transportation equipment to Canada in 2006, a 23 percent increase from 2005.

In other industries, export levels don't correlate as neatly with exchange rate fluctuations. For example, district exports of computers and electronic products correlate with the Canadian exchange rate to a lesser degree than other manufactured exports. Other factors, such as the strength of national economies and differing sensitivities to price changes, influence manufacturers' export decisions.

Nevertheless, in major sectors of the district economy such as food and non-electrical machinery, a strong relationship exists between exchange rates and exports. Between 2002 and 2006, district exports of non-electrical machinery to Canada rose at an annual average rate of 9 percent. Over the same period Wisconsin, a national leader in food processing, increased its exports of food and kindred products to Canada at an annual average rate of 12 percent.

Regardless of the sector, changes in the U.S.-Canadian exchange rate tug export levels in one direction or the other to some degree. Both Taylor and Bollen emphasized the price elasticity of exports: Shipments to Canada and other countries inevitably increase once prices adjust to a weaker U.S. dollar.

However, a fairly strong correlation between exports and exchange rates doesn't mean that exchange rates alone determine export levels. For example, exports to Japan correlate only weakly with the value of the yen. How can that be, given the relatively strong link between district exports to other countries and exchange rates with those nations? In the case of Japan, slack demand for district exports in a sluggish economy has likely trumped the price advantage of district goods due to a stronger yen.

Some trade experts discount the impact of the U.S.-Canadian exchange rate on exports. Economist Timothy Kehoe, an adviser to the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank, noted that imports from Canada have been growing at a faster clip than U.S. exports to that country. Oddly, this import growth is occurring despite a weaker U.S. dollar, which makes Canadian goods more expensive for Americans. Taylor attributes this apparent contradiction to the vastly different sizes of the U.S. and Canadian markets. The population of Canada is 28 million, less than one-tenth that of its southern neighbor. On balance, Taylor said, Canadian goods are more likely to find American buyers than vice versa. So it's not surprising that growth in Canadian exports to the U.S. should outstrip increases in the flow of goods headed the other way.

Opportunity knocks

Behind the statistics are companies such as Heatmor Inc., a manufacturer of industrial heating equipment in Warroad, Minn. Since the loonie began coming on strong five years ago, the company has shipped more and more of its output across the nearby border. "The Canadian market has grown," said Sales Manager Darrell Shaugabay. "In the past 10 years, we have seen an average annual sales increase to Canada of 75 percent. Our network of dealers has grown too."

A strong Canadian dollar has allowed Heatmor's Canadian distributor to keep a lid on retail prices, making the company's equipment price-competitive with Canadian products. As a result Heatmor has steadily increased its sales in eastern Canada, which in turn has required ramping up production capacity; the firm has doubled its manufacturing workforce to about 50 people in the past decade.

Kolberg Pioneer Mining, a manufacturer of mining and industrial equipment in Yankton, S.D., has also capitalized on the weak dollar by increasing its exports to Canada. "We've been doing really well selling conveyer materials-handling equipment into Alberta, and the exchange rate has helped," said Mark Mulloy, a sales manager responsible for Canadian exports. He said that the company plans to add crushing equipment used in road construction to the list of products—conveyor systems, washing and screening equipment—that it already sells in Canada.

Without a favorable exchange rate, Schollmeyer Engineering might not have ventured into the district's largest foreign market. The soaring Canadian dollar provided the impetus for the novice exporter to negotiate a Canadian distribution agreement, which Clarence Schollmeyer expects to boost sales. A Manitoba company will sell the firm's sprayer cradles throughout Canada's farm belt and smooth the export process by preparing customs forms and other documents.

For these and other district companies developing new business in Canada, a favorable exchange rate in recent years has been a crucial ingredient of success, stoking demand for U.S. goods. Today, with the Canadian loonie hovering 15 cents below parity with the U.S. dollar, manufacturers of a wide range of products are poised to make further inroads into Canadian markets.

But can district firms pursuing Canadian customers rely on a weak U.S. dollar in the future? Probably, according to trade experts. Taylor expects the dollar to stay on a downward course as overseas worries about the vigor of the U.S. economy persist. Kehoe doesn't anticipate much movement in currency values in the near future. So export opportunities will continue to knock for Schollmeyer Engineering, Heatmor and other manufacturers, not just in Canada but also in other foreign markets where the greenback is losing ground.

Associate Economist Rob Grunewald contributed to this article.