Access to credit can be a doorway to economic mobility. A car loan can mean transportation to a job. A mortgage can build intergenerational wealth. A credit card can help ride out an occasional rough patch in income—and help build up the all-important number that opens or closes that doorway to mobility: your credit score.

Credit scores have not been easy to study; they are private-sector and proprietary, a black box by design. In new research, MIT economist and Institute advisor Nathaniel Hendren and co-authors1 make significant strides via an unprecedented sample that combines credit score and payment delinquency data with Census Bureau and IRS records for more than 25 million Americans—including, in some cases, linked data for parents and adult children. The credit score in question is VantageScore 4.0, a product of the three major consumer credit bureaus that claims to cover 94 percent of U.S. adults.2

In “Credit Access in the United States,” the researchers examine credit score disparities for the first time “at a population scale, to really unpack the mechanisms of the determinants of access,” said Hendren, speaking at the Institute’s 2025 research conference. The results they report are extensive:

- There are stark credit score gaps by race, education, parental income, and geography—even after controlling for income.

- These gaps exist at the start of adulthood and shrink only modestly as people get older.

- The divergence in repayment history for young adults does not typically begin with mortgages, car loans, or even credit cards, but with delinquencies on smaller items like phone or utility bills sent to collections.

- Credit scores appear to suffer from two distinct forms of bias:

- Borrowers from groups with lower credit scores (including Black and Hispanic) receive higher scores than are borne out by future repayment activity.

- However, Black and Hispanic consumers with pristine past and future repayment history receive lower credit scores than White consumers with similar records.

- Credit scores of adults appear strongly related to the credit scores of their parents and the location where they grew up.

The new research is a product of the Opportunity Insights research initiative, which first formed around findings that a child’s neighborhood can affect lifetime financial and health outcomes. So it is, it would appear, with credit scores and repayment habits. “The credit differences that we observe in adulthood,” said Hendren, “we think have their roots in childhood.”

Persistent credit gaps and algorithmic biases

Age—and the accumulation of credit history—do not eliminate credit score disparities. At age 30, for example, the average credit score difference between White and Black individuals is 97 points. At age 60, the groups are still 92 points apart (Figure 1).

The gaps are similarly persistent between individuals whose parents had high and low incomes or different levels of education. There are also lasting differences between individuals who grew up in places with higher and lower average credit scores.

The researchers do not know the algorithm behind VantageScore. But knowing prior and future repayment histories of each person in the sample allows them to examine whether their credit scores accurately reflect the realized risk: how often the consumer becomes delinquent. This investigation reveals two common forms of “algorithmic bias.”

A “calibration bias” appears to favor consumers in groups that are more likely to become delinquent. Consider two consumers with the same midrange credit score of 650: One had low-income parents, and the other comes from a high-income family. On average, the consumer from a low-income background is 13 percentage points more likely to become at least 90 days delinquent on a line of credit within four years (Figure 2).

Between Black and White consumers with the same 650 credit score, there is a 14 point gap in subsequent delinquency outcomes. Hispanic individuals with a 650 score are about 5 points more likely than White individuals to become delinquent; Asian individuals are about 8 points less likely. “The credit score itself is understating the true differences in the delinquencies that it is trying to predict,” Hendren said. They found similar patterns by parental education and geography. The bias is largest in early adulthood and narrows as people build credit files in their 20s. After age 30, the gaps remain largely unchanged.

Groups that are advantaged by this calibration bias, however, are disadvantaged by a different type, or “balance bias.” This perspective focuses solely on consumers with spotless past and future repayment records. In this case, 25-year-old Black consumers are assigned an average credit score more than 30 points lower than White consumers; Hispanic scores are 13 points lower, while Asian scores are 10 points higher (Figure 3).

For Black consumers who maintain no delinquencies, the gap shrinks by more than half by middle age but remains meaningful. A comparison by parental income shows a similar trend.

The researchers conduct additional exercises to demonstrate that the biases they find are not intrinsic to VantageScore “or any other particular scoring method, but rather reflect a fundamental property of the information contained in the credit file.” They further note the much-cited theoretical finding from Institute advisor Jon Kleinberg that it is impossible for any risk score to simultaneously eliminate both forms of algorithmic bias as long as groups have underlying differences in delinquency rates.3

Payment patterns and the power of place

What can explain the underlying differences in repayment the researchers document across groups?

Financial circumstances, not surprisingly, play some role. The researchers draw on their extensive administrative data to control for income, savings, wealth, home equity, job stability, and more. Many of these do help explain repayment behavior, but far from fully.

Moreover, these financial controls do not resolve two observations from the data: Parental credit history is one of the strongest predictors of grown children’s repayment patterns, even when controlling for the child’s credit score, income, and wealth. This suggests, they write, “a channel of intergenerational transmission of repayment propensity that operates within the family,” such as children observing how parents handle the family finances.

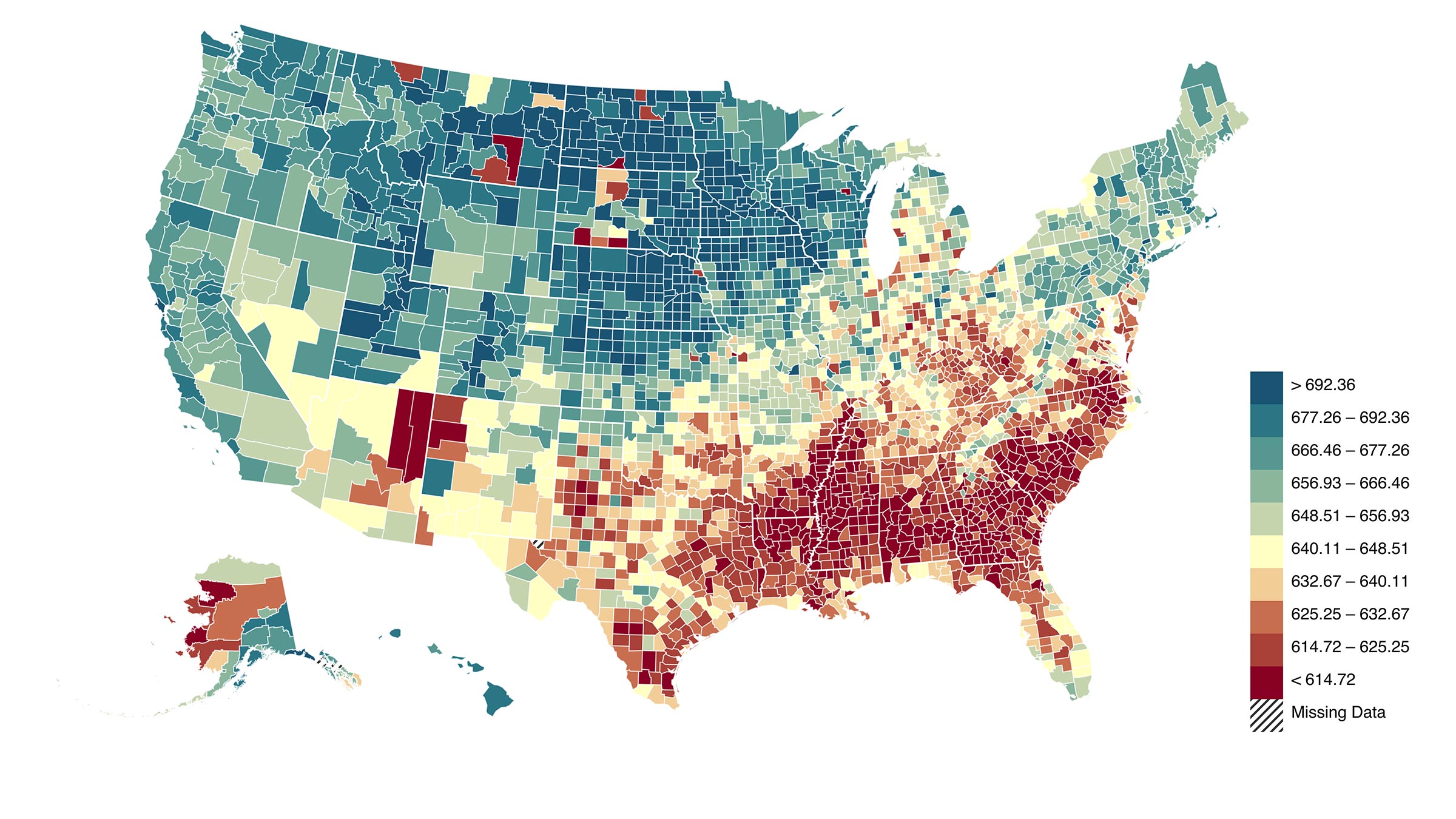

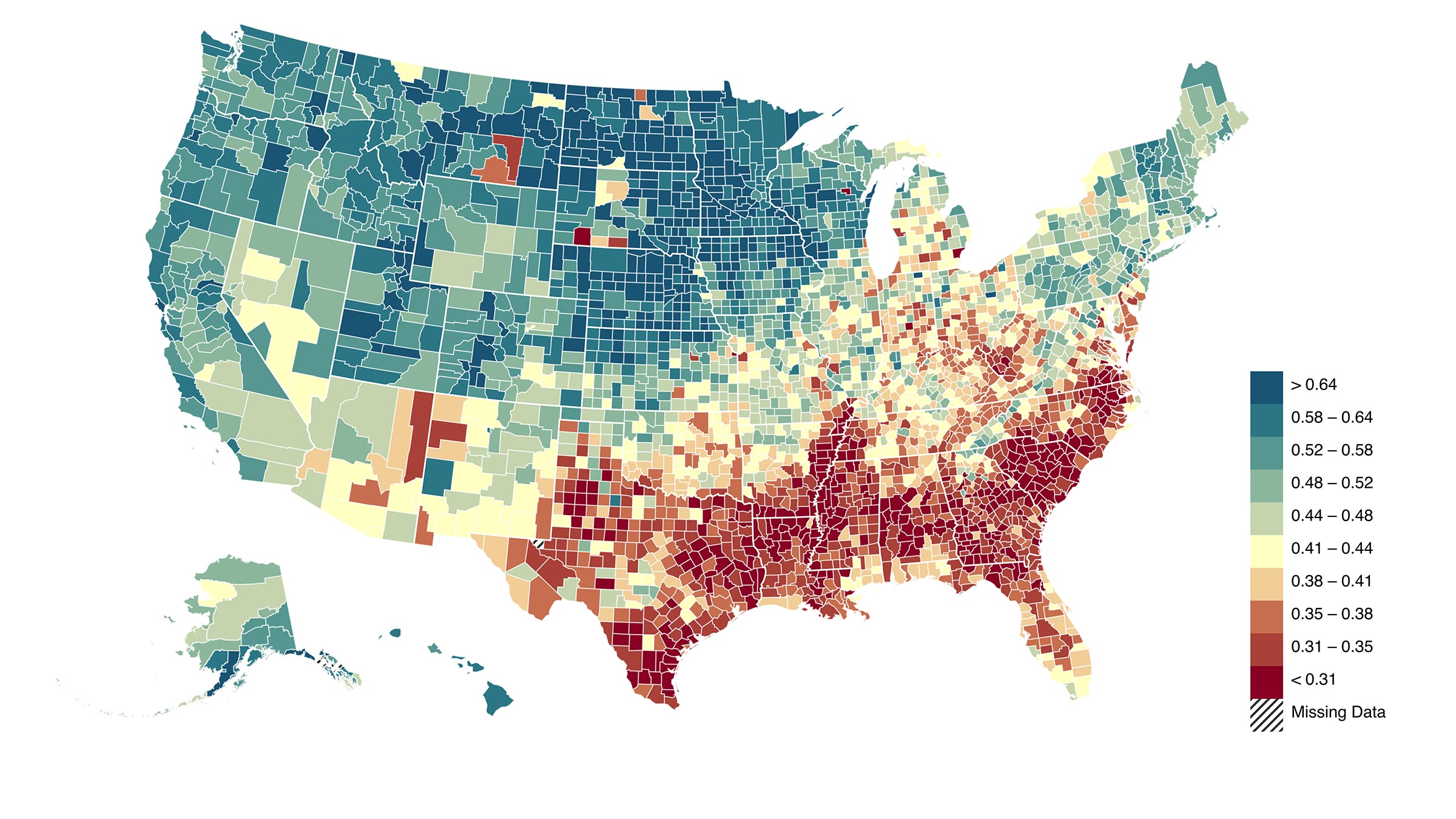

Second, consumers with similar financial profiles—but from different hometowns—have different credit scores and repayment tendencies, on average (Figure 4).

Similar incomes, different credit history

Source: Bakker et al., “Credit Access in the United States,” July 2025, using anonymized Census Bureau, IRS, and credit bureau data.

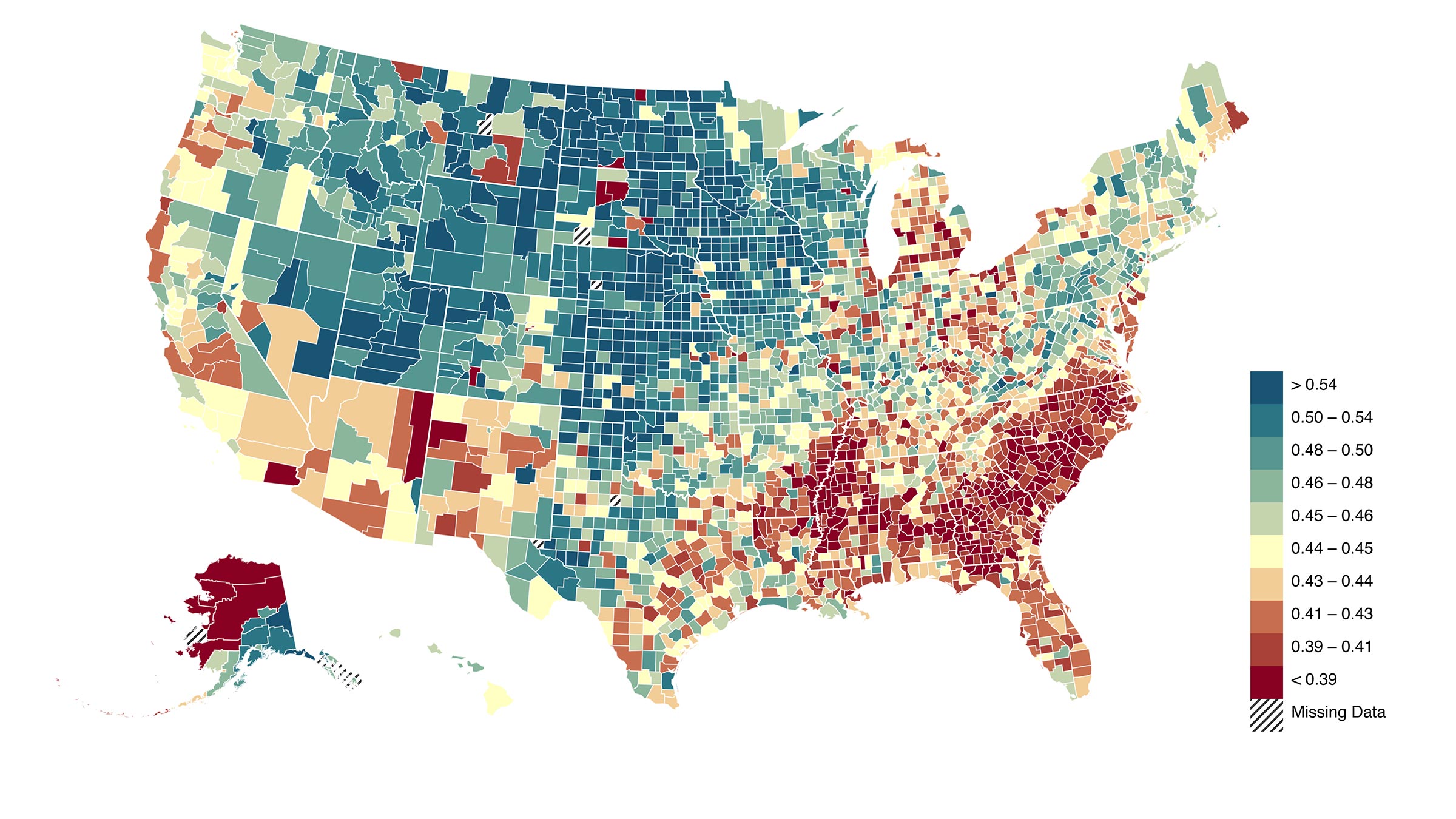

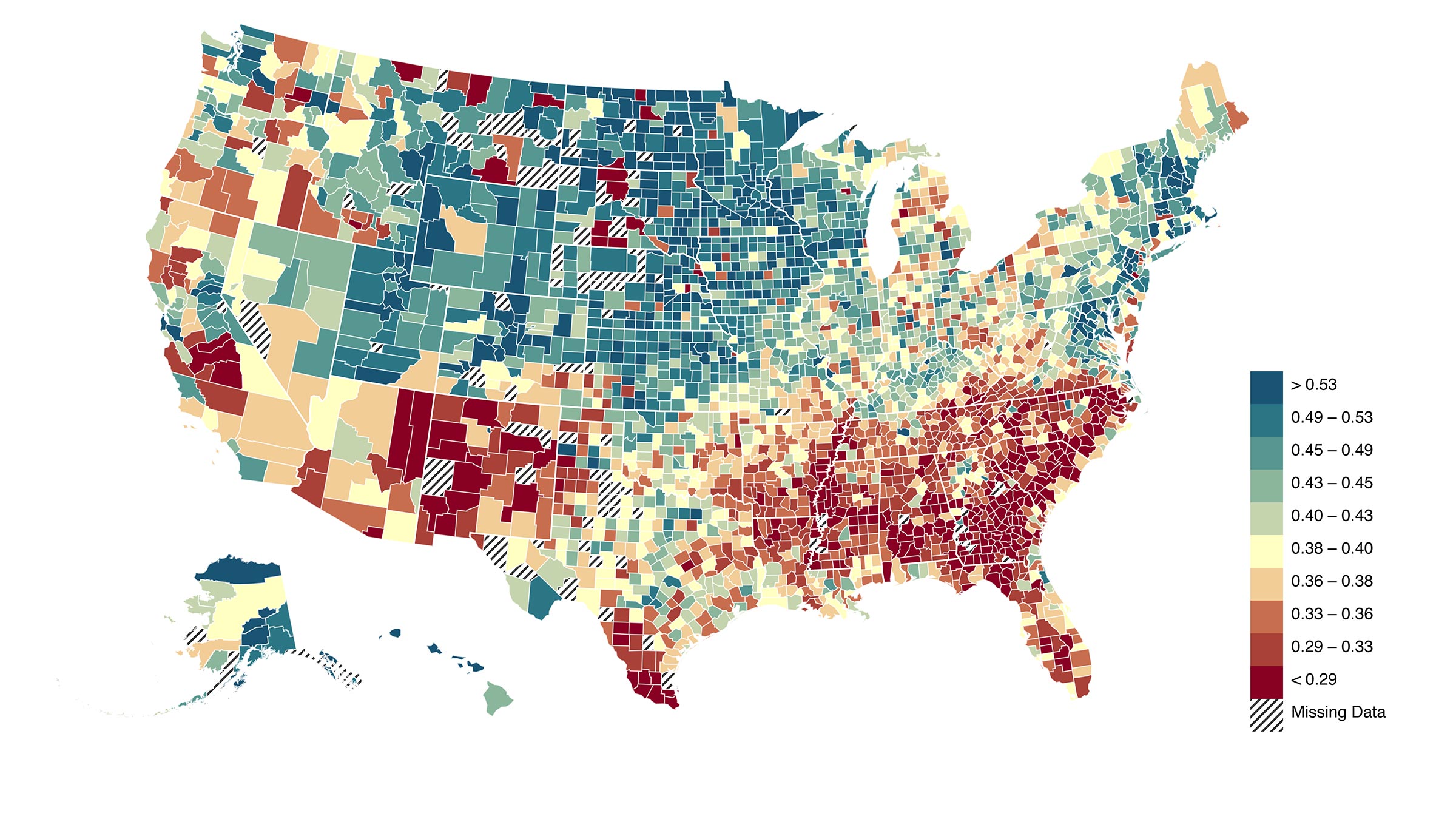

To estimate the causal effect of location on repayment, Hendren and his co-authors revive a technique from their well-known Moving to Opportunity research. They exploit the variation in outcomes between siblings who make a family move at the same time, but at different ages. “Children who spend more time growing up in a place where other people repay their debts are themselves more likely to repay,” they find, “even conditional on their income in adulthood.” They estimate, for example, that growing up in a low-credit-score area like Baltimore, Maryland, and the highest-credit-score county of Bergen County, New Jersey (just across the Hudson from New York) amounts to a 10 percentage point difference in the likelihood of having no delinquencies as an adult.

Why does place matter? A deeper explanation is left to future research. Initial investigations by Hendren and his co-authors do not find clear evidence of distinct causal effects from financial literacy or economic instability, though these are strongly correlated with credit habits. They suggest there is more potential in various mechanisms related to “social capital”: social networks, sharing of financial knowledge, and direct exposure to neighbors and friends with higher socioeconomic status. Their new maps of credit score and repayment overlap well with prior Opportunity Insights work to measure upward mobility and economic connectedness (Figure 5).

Geography matters

Source: Bakker et al., “Credit Access in the United States,” July 2025, citing prior research published by Opportunity Insights.

They further discuss the possible role of alternative credit sources, specifically pawn shops and payday lending, where exposure and availability vary greatly by geography.

In the modern economy, a good credit score and strong repayment habits are all but essential for economic opportunity. Using massive datasets to dissect these credit disparities is one large step toward knowing where—and when—to focus policy efforts. “Because these habits form early and are reinforced by parents and social networks,” the economists write, “policies that cultivate sound credit practices during childhood and young adulthood appear to be promising policy pathways.”

Endnotes

1 Co-authors: Trevor Bakker, U.S. Census Bureau; Stefanie DeLuca, Johns Hopkins University and Opportunity Insights; Eric English, U.S. Census Bureau; Jamie Fogel, Harvard University and Opportunity Insights; Daniel Herbst, University of Arizona.

2 Specifically, VantageScore 4.0 aims to predict the likelihood of an individual falling at least 90 days delinquent on a line of credit within two years. The researchers’ analysis uses VantageScore report information pulled at four-year intervals between 2004 and 2020. VantageScore is a joint product of Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. U.S. purveyors of credit scores are prohibited from using information other than reported credit activity (including race, location, age, or income). Credit, tax, and demographic data are anonymized and linked by the researchers at the individual level.

3 VantageScore has published its own findings of a lack of statistical bias against protected classes in its 4.0 model, using ZIP code data as a proxy for ethnicity.

Jeff Horwich is the senior economics writer for the Minneapolis Fed. He has been an economic journalist with public radio, commissioned examiner for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and director of policy and communications for the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority. He received his master’s degree in applied economics from the University of Minnesota.