A sea change is coming to the Ninth District labor force. In many communities, employers are already coping with an altered landscape in which established assumptions about labor availability no longer apply and strategies for hiring and retaining workers must be reassessed.

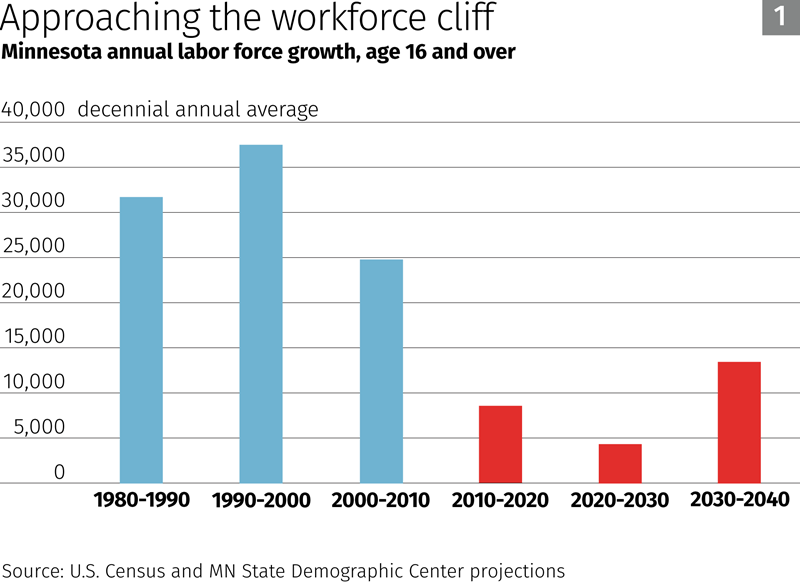

Minnesota State Demographer Susan Brower has done extensive research on the effects of population changes on the state’s economy and workforce. Largely due to the aging of the baby boom—the large generation born between the end of World War II and the early 1960s—Minnesota’s working-age population is projected to peak in 2021 and then decline before recovering after 2030. As a result, Minnesota’s total workforce will grow much more slowly than in the past (see Chart 1), increasing only because of greater labor force participation by seniors.

These changes—also under way to varying degrees in other district states—have profound implications for state economies and labor markets, including potential worker shortages and dampened economic growth.

A Minneapolis native and a member of Generation X (the demographic group that followed the boomers), Brower frequently travels around the state to talk about demographic shifts and what they mean for Minnesotans.

Brower spoke to the fedgazette about the ramifications of these changes for the workforce and the broader economy, both in Minnesota and in other district states.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

fedgazette: How could a declining working-age population and slower-growing workforce affect the Minnesota economy?

Brower: The concern is that employers would be constrained in growing their companies if they’re not able to find the workers that they need. A limited supply of workers, now and in the future, could translate into overall lower economic output and growth. There’s a bunch of things that make the picture more nuanced than that, of course, but at the base, if you think about the number of people who go to work every day to produce goods and services, if that number isn’t growing as fast as we’ve become accustomed to in the past, it’s just much harder to grow the economy.

fedgazette: So is the state’s economic output—and Minnesotans’ standard of living—expected to grow more slowly or stall over the next decade?

Brower: Not necessarily. There are other potential sources of economic growth to counter slower workforce growth, such as increases in productivity through automation. Another way to boost productivity, one that you don’t think of as much, would be to produce goods and services of greater value, even though you might have the same number of people.

fedgazette: Do other states in the region face a similar economic scenario because of demographic change?

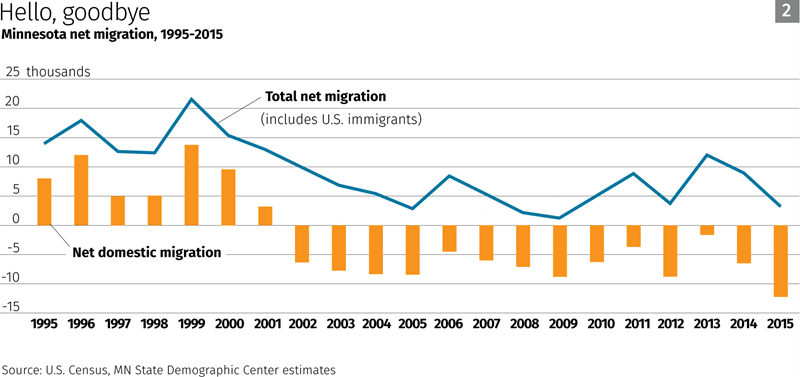

Brower: Part of what is producing the workforce slowdown is the expected exit of the baby boomers from the labor force. The baby boom didn’t just take place in Minnesota; it took place across the United States and in a lot of the rest of the globe. So many other states have large shares of their populations moving into the retirement years. Domestic and international migration is one way you potentially make up for some of the losses of the baby boomers, and some states have done better with respect to in-migration than others.

North Dakota, for example, has seen a great deal of in-migration due to the oil boom, although if we looked at the most recent population projections, we would likely see a drop-off in domestic migration to North Dakota because of cutbacks in oil production.

fedgazette: You’ve talked about the importance of attracting and retaining talented workers, especially younger people in high-tech and creative occupations. But since the early 2000s, Minnesota has experienced a net loss of people to other states (see Chart 2)—most of them, your research has shown, young people in their college years who leave the state and don’t return. What can be done to reverse this net outflow? Is there a role for public policy here?

Brower: There’s been more and more interest by the corporate sector in attracting people to Minnesota. There’s been this initiative by Greater MSP in the Twin Cities to attract young professionals, to understand the factors informing their decision to move here. What is it about Minnesota that’s important to them once they get here? They’ve worked to try to create, in a really genuine way, the social connectedness that’s important to young adults. I think it’s too soon to tell how effective it’s been, but it’s an example of a concerted effort by a group of people to do something about this issue.

One thing that’s a potential public policy concern is the role of Minnesota public colleges and universities in retaining young people in the state. Do we incentivize leaving? Are young people moving away to go to college elsewhere because it’s less expensive? We don’t know enough about the decision-making process of young people who choose to leave. Filling that hole in our collective knowledge about young people’s migration decisions could be especially useful to us over the next 10 to 15 years as we try to stop some of these losses.

fedgazette: When labor is scarce, the traditional way for employers to compete with other firms is to offer higher wages and benefits. In the future, to cope with even tighter labor supplies, will employers have to develop new approaches to hiring and retaining workers?

Brower: There are a number of different ways in which employers are doing that. There are all kinds of creative approaches that employers are taking to being more flexible, whether it’s offering flextime, contracting with workers, accommodating people with physical limitations. Maybe there are older adults who are thinking about retirement, but don’t want to fully commit to retirement or work. They want something in the middle, and a flexible schedule or the ability to take periods of leave would make staying on the job more palatable.

Employers have looked at how they can attract and keep parents; again, that might require flexible work schedules, or some help with day care. Another strategy is developing untapped potential or talent where it’s been underutilized in the past, particularly in populations of color or immigrant communities.

My department with the state has looked at creating career pathways to increase retention. We’re a relatively old agency; we have a lot of people who are just around the age of retirement. We’ve been looking at creating jobs that provide opportunities for advancement, that give entry-level employees a chance to graduate to higher positions in the organization.

fedgazette: In a presentation you made earlier this year to the Minnesota High Tech Association, you said that demographic change in Minnesota will “bring new opportunities, and a new license and impetus for innovation.” Could you elaborate on that statement? What are some upsides to slower labor force growth in coming years?

Brower: We can think of innovation in terms of finding efficiencies that we didn’t find before. Are there technologies that we can adopt that make individual workers more productive? If labor is in scarce supply, and expensive because of increasing wages, the relative cost of taking on a new technology is reduced. I’m hearing from manufacturers that they’re choosing to move toward automation because they see that the time is right, that the labor supply is such that it makes sense to invest now. Potentially, there can be solutions that we’re kind of pushed toward, because of this labor situation, that improve efficiency and productivity. Service industries in which tasks are physical and repetitive—I’m thinking about retail, food service, food preparation—could also benefit from innovation.

Another policy implication of all of these trends is the importance of education and training; when you have a scarce supply of potential workers, how do you increase the skills of the workers that you do have, so that they can produce more valuable goods and services?

fedgazette: Are employers, educators, lawmakers and others in our region still adjusting to the idea of these changes we’re talking about? Do ingrained assumptions about population trends and labor availability make it harder to find solutions to workforce challenges?

Brower: Many times we are somewhat encumbered by our ability to keep doing what we’ve done in the past, out of habit. Some of these demographic changes will force us out of those habits and move us toward change. I don’t think it needs to be a gloom-and-doom situation. I’ve been talking about this since I’ve been in this position, and compared with five years ago, when we were coming right out of a recession, I get many more nods of recognition from people who are experiencing labor scarcity. I think it’s starting to resonate with people as they’re receiving fewer and fewer job applications.

fedgazette: Thank you, Susan.