Recent heavy rains have brought relief to drought-stricken parts of the Ninth District, but months of dryness have exacted a heavy toll on crops, cattle herds and natural resources that is likely to weigh upon regional and local economies for months to come.

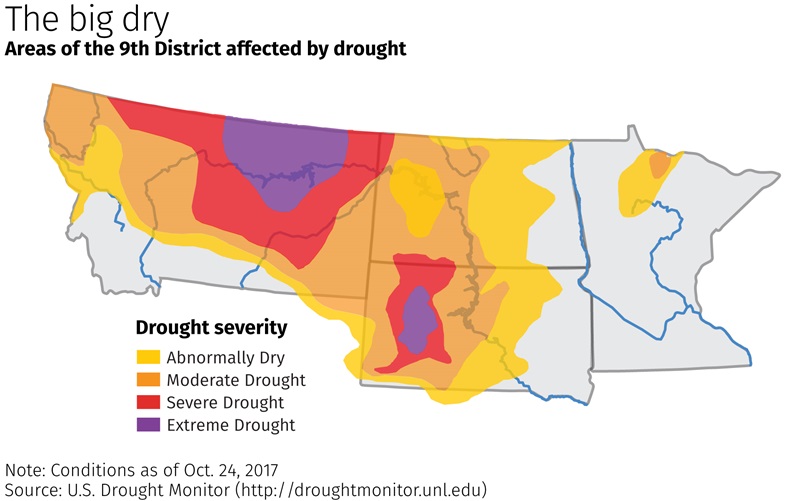

In late October, two-thirds of the district was still experiencing some degree of drought, according to the latest U.S. Drought Monitor (see map), a weekly overview of affected areas of the country.

A so-called flash drought hit the Northern Plains in early May; the sudden onset of high temperatures coupled with scant rain sucked moisture from the soil, first in a few counties in eastern Montana and southwestern North Dakota, then in other parts of those states and in South Dakota.

Drought conditions spread and intensified over a scorching summer and into the fall. In media reports, farmers and ranchers have said that the drought is the worst they’ve ever seen. The governors of Montana and North Dakota have declared drought disasters in their respective states.

Heat and dryness hit Montana especially hard; in mid-September, every county was drought-stricken, and half the state was in extreme or exceptional drought, the severest categories tracked by the Drought Monitor. North Dakota wasn’t much better off, with over half its area in severe or extreme drought. The state’s southeastern corner, including Richland and Sargent counties, was the sole area untouched by drought.

September rains eased conditions in many parts of Montana and the Dakotas, but as of late October, two-thirds of Montana was still in severe drought or worse. Most of South Dakota was experiencing some level of drought, with the worst conditions west of the Missouri River.

Minnesota, Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan were relatively unscathed by drought. Moderate drought afflicted northwestern Minnesota over the summer, but by the fall, most of the state was drought-free. In late October, the western U.P. and parts of Wisconsin in the district remained abnormally dry.

Too little, too late

The persistent dryness has imposed hardship on agricultural producers. In many areas, rains have come too late to stave off major crop losses. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) predicts dramatically lower production of spring wheat, corn and other crops this fall compared with 2016 (see table). North Dakota’s spring wheat production is projected to drop by almost one-third year over year to 186 million bushels. Montana farmers are on pace to harvest 76 million bushels of winter wheat in 2017, the lowest production since 2004—another drought year.

| Montana | North Dakota | South Dakota | Minnesota | U.S. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter wheat | -28% | -74% | -61% | n.a. | n.a. |

| Durum wheat | -66% | -56% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Spring wheat | -39% | -31% | -32% | 4% | -25% |

| Alfalfa hay | -13% | -21% | -13% | -21% | -4% |

| Corn | n.a. | -17% | -16% | -11% | -6% |

| Soybeans | n.a. | 1% | -6% | -2% | 3% |

|

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture * Corn and soybean projections based on Sept. 1 yields per acre; other crops Aug. 1. |

|||||

But there’s an upside to the drought for farmers who manage to harvest a respectable crop this year. Tightening supplies of wheat and hay have driven up prices of these commodities since the spring (Chart 1), reversing three years of flat or declining prices that have depressed farm incomes in Montana and the Dakotas, leading U.S. wheat-growing areas.

In June, the price of North Dakota hay rose almost 70 percent year over year, according to USDA figures. In contrast, prices for corn and soybeans haven’t risen appreciably during the drought; these important district crops are mainly grown in areas of the district that have received more rain, such as southern Minnesota and eastern South Dakota.

Much of the region affected by the drought is prime cattle country, and ranchers are struggling with harsh conditions. Drought has ravaged pastureland in Montana and parts of the Dakotas (Chart 2), shriveling grass and forcing ranchers to buy expensive hay to sustain their herds.

In response, the USDA announced in June that it would allow emergency grazing on environmentally sensitive Conservation Reserve Program lands in the Dakotas and Montana. And North Dakota agriculture officials have organized a “hay lottery,” the first of its kind in the country; ranchers who apply to the program have a shot at hay donated by farmers in other parts of the country.

Parched pastures and elevated hay prices have led some cattle producers to cut their losses. More than 40,000 cattle have been sold in auction barns in Miles City and Billings, Mont., since July, according to the USDA Marketing Service. That’s about 18 percent more animals auctioned than during the same period last year.

The drought has also increased wildfires and degraded wildlife habitat—a blow to regional economies that depend on recreation and tourism. Montana has suffered one of the worst fire seasons in its history, with over 1 million acres burned and more than 70 structures lost so far this year, according to the Northern Rockies Coordination Center, a clearinghouse for fighting wildfires. In North Dakota, over 6,000 acres have been blackened by fire.

In addition to crops and rangeland, flames have consumed properties in national parks, including the historic Sperry Chalet in Montana’s Glacier National Park, which was destroyed in August.

Pheasant and waterfowl hunters represent a major source of revenue for hospitality and other businesses in Minnesota and the Dakotas. On the heels of a cold and snowy winter, the drought dried up duck ponds and stunted nesting cover for pheasants, reducing hunting opportunities.

Pheasant roadside counts in South Dakota were down 46 percent year over year in August, according to the state Game, Fish and Parks department. Pheasant numbers also fell in Minnesota, although 2017 losses were likely due in part to a statewide decline in nesting cover since the mid-2000s.