Everybody wants to be green these days. A popular farmland conservation program is getting greener, yet some farmers enrolled in it are nonetheless seeing a different shade of green: the color of money.

The Conservation Reserve Program is a federal program that pays farmers and other landowners to withhold environmentally sensitive (and often marginally productive) land from production for a decade or longer. Enacted in 1985, CRP has become popular among farmers, environmental groups and policymakers for achieving the difficult dual objectives of protecting the environment while helping to stabilize farm income.

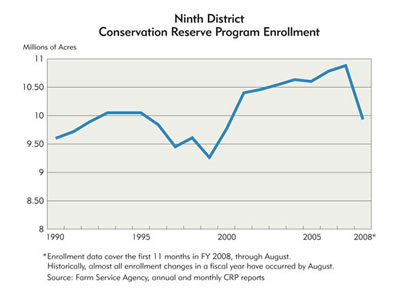

The program is undergoing a change, however. The number of acres in CRP fell significantly this past year, which grabbed headlines in district newspapers. The main reason is a booming farm economy, which has given farmers an incentive to put acres once enrolled in the program back into production.

At the same time, and largely unnoticed, the program's emphasis has been slowly shifting away from the protection of large swaths of farmland and toward strategic coverage of land with higher environmental value. The sum of these coincidental trends: Total acreage in CRP is dropping and will likely continue to fall, yet environmental outcomes might improve nonetheless.

ABCs of CRP

In the past year, CRP acreage declined by the largest margin ever. From September 2007 to August 2008, CRP acres nationwide declined by 2.1 million acres, the biggest annual drop since 1998, according to data from the Farm Service Agency (FSA), the branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) that runs the program. (CRP contracts expire in September. At the time of this analysis, a full-year comparison—September to September—was not available. However, based on past sign-up history, almost all landowners have made their enrollment decisions in a given year by August.)

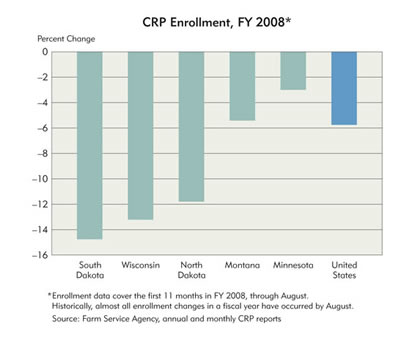

Ninth District states enroll a disproportionate number of acres in the program—about 30 percent. The decline in CRP acreage over the past year is also more pronounced in the region, dropping by about 950,000 acres, easily the highest annual decline in the district since the program's inception. CRP acreage declined in all district states, but the drop was particularly large in the Dakotas, where more than 600,000 net acres were pulled out. (See charts below.) Michigan was not included in this analysis because the only portion in the district, the Upper Peninsula, has a tiny share of the state's CRP acreage.)

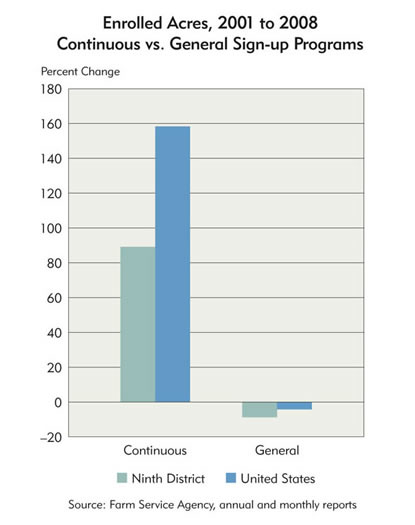

While overall CRP acreage is declining nationally and in the district, a closer look at the program reveals two separate and divergent trends. First, a little background. Broadly speaking, CRP has two separate programs: The "general sign-up" program targets large swaths of production acreage; a second program, dubbed "continuous sign-up," protects smaller, more environmentally sensitive parcels, like those bordering waterways.

The two programs are mostly headed in different directions. The general sign-up program encompasses almost 90 percent of all CRP acres, but is shrinking. In contrast, the smaller continuous sign-up program has been growing like gangbusters, but involves a comparatively small patch of grass.

REX doesn't fetch farmers

Most of the decline in the general sign-up program has taken place in the past fiscal year and is the result of a strengthening farm sector since 2006 that has changed the economics of idling farmland. By coincidence, that same year the FSA got a sneak preview of farmer intent regarding CRP when it unveiled a sign-up program to spread out the number of contracts that expire annually.

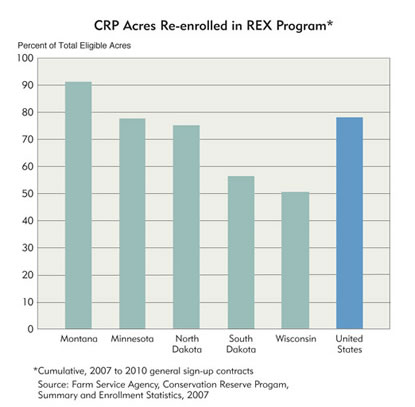

Historically, CRP contracts have expired in large bunches at the end of each decade because there was a huge initial sign-up for the program in the latter half of the 1980s and contracts were for 10 years. In an effort to smooth expirations, the FSA introduced a re-enrollment and extension program (REX) for all general sign-up contracts expiring between 2007 and 2010, which involved about 80 percent of all CRP acres, both nationally and in the district.

The REX program did nothing to change CRP acreage at the time. Even those who planned to exit CRP still had to wait until the original contract expired. But REX opened a window to the likely enrollment trend that lay ahead for CRP, because farmers haven't been given a second chance to re-enroll in the general sign-up program after declining through REX.

After REX deadlines passed, the FSA found that only about 82 percent of general sign-up acres were renewed or extended nationwide; in the district, the renewal rate was even lower, 78 percent. The re-entry rate varied significantly among district states and was particularly low in South Dakota and Wisconsin (see chart).

Mike Held of the South Dakota Farm Bureau said the drop in CRP acreage in that state was due mainly to landowners looking for a better return on crops. In South Dakota, corn is the number one crop, followed by wheat and soybeans, all of which are commanding high prices.

In South Dakota, for example, the average payment per acre of CRP land was about $39 as of August 2008. By comparison, a South Dakota State University analysis in February calculated average returns to management and labor at more than $200 per acre of corn using a corn price of $4.24 per bushel.

Nonfarming landowners and retired farmers-folks who don't turn the soil themselves-also are finding incentives to pull land out of CRP because farmland rental rates are rising along with crop prices. In 2007, average farmland rental rates in South Dakota were 20 percent higher than the state's average CRP payment in almost two-thirds of the state's counties, according to data from the USDA. There are also widespread reports that rental rates have risen significantly in some areas this year because of high commodity prices.

(One caveat: CRP land tends to be less productive and therefore less valuable from a rental standpoint. But no data are available on rent differences between land previously enrolled in CRP and other farmland. For more discussion of trends in rental rates and other farmland issues, see the July issue of the fedgazette.)

The new CRP

A slow and relatively quiet transition also has been afoot within CRP, one that emphasizes the protection of the most environmentally sensitive land.

The continuous sign-up program is made up of smaller programs that target different types of sensitive land, particularly wetlands. Such parcels are not competitively bid (as with general sign-up, where the FSA accepts low bids to idle land) but are automatically enrolled provided the land and producer meet certain eligibility requirements.

The government pays considerably more per acre to have these sensitive tracts taken out of production. In Minnesota, payments for general sign-up acreage averaged $52 per acre last year, while payments for continuous sign-up were about $91.

The payment disparity is a big economic reason that acreage in the continuous sign-up program has ballooned since 2001, while acreage has dropped in the general sign-up program (see chart). However, the average parcel in the continuous program is significantly smaller—again, because it targets the most sensitive lands-which is why overall CRP acreage is down. Last year, the general program lost almost 1 million acres in the district, while the continuous program added about 26,000 acres.

Some states rich in environmental assets are seeing a more dramatic impact from increasing emphasis on the continuous program. For example, CRP acreage in Minnesota, the land of 10,000 lakes, fell the least of any district state last year—just 3 percent. In 2008, 22 percent of the state's CRP acreage was enrolled in the continuous program, compared with the national average of 12 percent.

The trend line for both CRP programs appears unlikely to slow down or veer anytime soon. For example, the FSA extended this year's annual deadline to transfer general sign-up land into the continuous program from September to May, giving landowners an extra eight months to choose that option after their original contracts had expired.

For the general sign-up program, high commodity prices have ratcheted up pressure to farm all available land, and the program is not actively seeking new general sign-ups. For the past two years, USDA Secretary Mike Johanns announced there would be no new sign-ups for the general program, and a Wisconsin FSA representative said there will be no general sign-ups offered in the next few years.

This news goes hand-in-hand with the latest provisions outlined in the 2008 farm bill passed last May that capped CRP acreage at 32 million acres nationwide, a 7 million acre reduction from the 2002 farm bill. August enrollment stood at 34.7 million acres. The new cap must be achieved by 2010 and will remain in place until 2012.

Looking for cover

Despite pressures driving down overall CRP acreage, a stampede out the door is unlikely. First, opting out of CRP contracts early carries stiff penalties: All CRP payments over the lifetime of the contract must be repaid, along with a penalty fee.

Getting out of a contract is even more problematic for most landowners who, back in 2006, participated in REX. Through the program, roughly three-quarters of contracts—many of which would now be expired or nearing expiration—were extended for two to five years. Sounds innocuous enough, but lengthening the contract increased the cost of opting out. The most environmentally prized land received new contracts in the REX program, which reset the repayment ticker for contract holders who decide to terminate early.

Current farm conditions have put added pressure on the FSA to allow CRP contract holders to opt out early without penalty; with considerable acreage tied up in CRP, the farm sector hasn't been able to respond to rising global demand for a variety of commodities, but especially for corn, which is being driven by increasing ethanol production. Many states that before were not known as ethanol producers are experiencing a boom.

“Six or seven years ago, Wisconsin did not have any ethanol plants,” said Paul Zimmerman, from the Wisconsin Farm Bureau. “Today, we have seven plants in our state.”

Despite considerable lobbying earlier this year for the USDA to waive early opt-out penalties for CRP contracts, Johanns indicated that the agency would not oblige. Environmentalists and sportsmen's groups oppose early opt-outs. Many bird hunters, for example, believe that CRP has been critical to improved hunting conditions. In the Prairie Pothole Region of the Dakotas, CRP land has contributed to measurable gains in wildlife populations. An FSA-commissioned study last year of grassland bird populations in the region credited CRP with increases of roughly 1.1 million bobolinks and 320,000 sedge wrens.

Agricultural considerations also play a role in CRP enrollment in district states. Montana, for example, saw only a 5 percent drop in CRP acreage this year. Despite good moisture this year, Montana is not far removed from drought conditions, which makes it economically difficult for farmers to take their land out of the program, according to Glen Patrick from the Montana FSA office. He pointed out that it takes a great deal of inputs to get land back into production in the first year when the ground is dry. (An analysis this past summer by Dwight Aakre of the North Dakota State University Extension Service calculated the startup costs of bringing CRP back into production in that state at almost $55 an acre.)

The type of crops grown in a state also has a bearing on how much CRP acreage gets plowed up. Though crop prices have been high virtually across the board, corn and soybeans tend to offer better returns, particularly in certain areas. That's probably another reason CRP exits have been lower in Montana, according to John Youngberg of the Montana Farm Bureau, because neither corn nor soybeans are a major crop in the state.

“In areas where they plant higher-value crops such as corn and (soy)beans, it may be more economically feasible to plow up CRP. In Montana, where the majority of our cropland is wheat or barley, it might not be as compelling an argument,” Youngberg said.

Looking for more green

There has been much speculation about the future of CRP in light of strong farm commodity prices.

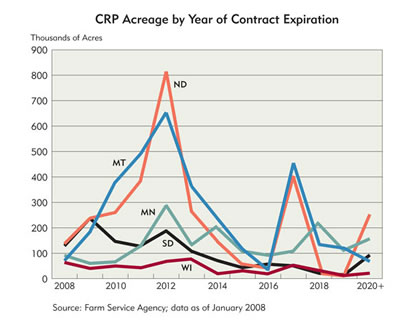

Thanks to the many thousands of CRP contracts that saw short-term extensions under REX, better than half of all contracts will expire between 2009 and 2012. From now through 2020, each district state will see a varying trend of expiring acreage, but a clear and growing spike awaits in 2012 (see chart). The question is how much of that acreage will be re-enrolled.

In the long run, farm prices will dictate the level of participation in the general sign-up program. Should prices stay high, enrollments are likely to decline unless the program raises average payments.

At the same time, however, states are starting new programs that coincide with federal interests in targeting more environmentally valuable land for retirement. Earlier this year, for example, the South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks proposed enrolling 100,000 acres in the James River Watershed Basin—widely recognized for its great potential as a wildlife habitat—into a specific CRP environmental program. This would be the first program of its kind in the state, and supporters hope that it will improve water quality and help reduce soil erosion as well.

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.