Small business is the economic version of Darwinism. Compete or die. And many do die, by the thousands every day. Equally important, many thousands are also born every day. As a society we love to celebrate new business openings and mourn most every closing—with the local media often in tow at both events. Yet there is little understanding, short of anecdote and intuition, of which side is winning or losing, and by how much.

Economists call this birth-and-death cycle "churn" and cite it as a critical component of a dynamic economy because new businesses bring innovative ideas, replacing old businesses that can't adapt to changing market needs and tastes. While there is certainly hardship for some, in the broader view efficiency, innovation and productivity win out, and society is more prosperous as a result.

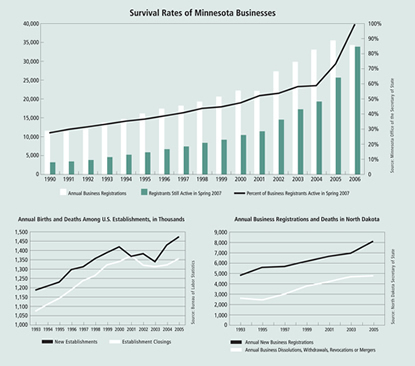

Broad measures at the national level track establishment births and deaths. Figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that births have been rising steadily, but so have deaths. The result has been a steady increase in the number of new businesses, although net gains lessened during the 1990s, turned negative in 2001 when the country went into recession and finally rebounded by 2004 and 2005 (see chart).

But despite the seeming importance of business churn to the economy and to policymaking—government wants to promote births and limit deaths—very little is known about churn at the state level. This is somewhat unusual, given that births and deaths are tangible, recordable events.

North Dakota offers a unique window on births and deaths through its business registration records. Though all states register various businesses (corporations and other legal entities) upon their start-up of operations, not all of them keep particularly detailed annual records of new registrations. North Dakota happens to do so, and it also tracks firms that are dissolved or merged with other businesses (a useful, if imperfect proxy for deaths, given that mergers typically do not involve the closing of a business).

The total number of registered businesses in North Dakota increased 122 percent from 1993 to 2005, according to data from the secretary of state's office, so it's obvious that there have been more births than deaths. (Note: Registration data do not include the multitude of sole proprietorships that are not required to register with the state.)

But in terms of business churn, it's instructive to see that new annual registrations grew from about 4,800 in 1993 to over 8,000 in 2005. On the flip side, businesses that were dissolved, merged or otherwise stopped doing business grew from roughly 2,600 to 4,700 over the same period. Though proxy deaths grew at a slightly faster rate than births, the annual net gain in new businesses nonetheless increased from about 2,200 firms to 3,300 firms (see chart).

Survival of the fittest

Although there is no perfect substitute for business births and deaths, other sources of information offer some insight into survival rates of small business.

Amy Knaup of the Bureau of Labor Statistics made one of the few formal attempts to define small business survival rates in 2005. Tracking a sample of firms over a four-year period from their founding in the first quarter of 1998, Knaup found that 66 percent of start-ups survived their first two years and 44 percent lasted at least four years. Survival rates varied across the sector, with information technology firms having the lowest survival rate, and health and education firms the highest.

In a follow-up study, Knaup and Merissa Piazza tracked the same businesses for an additional three years. Their results, released last December, showed that death rates after four years of business slowed considerably. After seven years, one-third of the original businesses were still operating.

The state of Minnesota tracks business registrations in a way that demonstrates a similar pattern of business survival, although its methods aren't exactly comparable to Knaup's research. The secretary of state records the annual number of newly registered businesses and also keeps an annual tab on how many are still operating. So instead of a longitudinal survey that tracks a group of firms over time, Minnesota records offer a survival snapshot of businesses registered in a particular year (see chart). Going back to 1990, this collection of snapshots suggests—much like Knaup's research and conventional wisdom—that the first year or two see a high number of business casualties. After that, the survival rate ebbs very gradually.

Don't know what we don't knowDon't bother looking for many more numbers on births and deaths or survival rates of small firms. Despite society's interest in the matter, and crucial to its economic well-being, very few data exist on business churn at the state level, and even national data leave much to be desired. Federal agencies have published some information, but there are some eye-popping inconsistencies. For example, data from the Small Business Administration (culling information from the Statistics on U.S. Businesses from the U.S. Census Bureau) suggest that 1,864 firms with 500 or more workers were born in Minnesota from 2002 to 2003. Never mind that fewer than 500 firms with that many workers exist in the entire state. Back in May, the National Research Council released a voluminous report on the data-gathering machine in place to track churn (also called business dynamics). It pointed out that current surveys and other data efforts were put in place mainly to track large, mature companies in order to better understand total output and job creation—not a bad idea, the report said, given that a relatively small proportion of firms is responsible for a large share of both. Call it the glass-half-full perspective. But the report also points out the empty half of the data glass, noting that "the U.S. business data system is inadequate for understanding many of the mechanisms leading to greater productivity and innovation" that stem from the creation and destruction of both firms and jobs. Although this country is considered an entrepreneurial leader because of its ability to create new markets and economic sectors, "there is very little precise information about how this mechanism actually works." While one might argue that such market mysteries don't need divining, government has been very interested of late in facilitating business creation. Without a better understanding of business dynamics and churn, the report added, efforts to encourage entrepreneurship and help sustain small business might be not only misdirected, but harmful to the very phenomenon that policymakers cherish. |

Ron Wirtz is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Ron tracks current business conditions, with a focus on employment and wages, construction, real estate, consumer spending, and tourism. In this role, he networks with businesses in the Bank’s six-state region and gives frequent speeches on economic conditions. Follow him on Twitter @RonWirtz.