In western North Dakota, the oil boom spurred on by soaring crude prices is big news. But a little farther to the east, folks are hoping to cash in on a different energy source: canola.

Two cities, just 20 miles apart, have seen ground broken for huge biodiesel plants this year. In Minot, a group of investors operating under the name Dakota Skies Biodiesel is working on a $56-million, 30-million-gallon plant that will be operational in August 2007. And in Velva, agribusiness and ethanol titan Archer Daniels Midland is building what will be the largest biodiesel plant in the country, pumping out 85 million gallons of the alternative fuel annually.

Everett Dobrinski, president and CEO of Dakota Skies, and a canola grower, says he got interested in the fuel years ago when he ran his farm equipment on biodiesel derived from sunflowers for two years as part of a study at the University of North Dakota. "I got pretty excited about it because I saw some really good results on that, and I was just kind of waiting for 25 years for the economics to get there to make it work," he said.

It seems the economics of biodiesel have arrived. In addition to the North Dakota plants, a number of other biodiesel ventures have sprung up across the district in the past two years. Two large plants are already operating in Minnesota, in Albert Lea and Brewster. And plants are under construction in Gladstone, Mich., Volga, S.D., and Eau Claire, Wis. The potential output of plants operating in the district is about 72 million gallons a year, with another roughly 165 million gallons of capacity under construction.

Increased investment and interest in biodiesel is part of a national trend prodded by rising petroleum prices, interest in sustainable fuels, concern over global warming and the specter of the country's "addiction" to foreign oil. Most of the interest in renewable fuels has focused on ethanol, which is alcohol made from carbohydrates, as opposed to biodiesel, which is made from fat. But biodiesel has also attracted attention, thanks in part to endorsements by high-profile advocates, such as President George W. Bush and country music icon Willie Nelson.

The district's attraction to biodiesel manufacturers is obvious: hundreds of thousands of acres of soybeans and canola, the chief crops used to make the fuel. For the same reason, Iowa is home to at least four sizable plants, with eight more under construction.

Some ag pundits point to biodiesel's phenomenal growth in recent years and tout it as the savior of the rural economy—the fuel to power America's future, grown right here in the heartland. But can the golden-hued fuel live up to this shimmering rhetoric?

A strong case can be made for biodiesel as a replacement for standard diesel fuel (petrodiesel): It's easy to make, can run in any diesel engine, burns extremely clean, has a higher cetane rating (the diesel equivalent of octane) and can be distributed through existing oil pipelines and terminals. Biodiesel is already a significant motor fuel in the European Economic Community, which produced six times the U.S. output in 2005.

However, there are reasons to be skeptical of the biodiesel-as-miracle-fuel story. If a generous federal tax credit were canceled, production of the fuel might falter. Add uncertainty over future oil prices, the technology's dependence on subsidized crops—which are also needed to produce food—and lingering worries about its effect on engine performance, and the fuel no longer looks like a sure-fire moneymaker for farmers, or an antidote to oil addiction.

Old fuel in new tanks

For all the recent buzz, biodiesel is an old fuel; transesterified vegetable oil was first developed in the 1850s. The recipe for biodiesel is not more complicated today, said Doug Tiffany, a research fellow in applied economics at the University of Minnesota who studies renewable energy policy. "You and I could make up a batch in our bathtub if we wanted to," he said. "But we'd have kind of a smelly mess there with the lye and so forth, so I wouldn't advise it."

The primary ingredient is fat, from any source. Soybeans are most common, and canola is popular in Europe (where it's called rapeseed) and the Dakotas because of the large amount grown there. But biodiesel can also be produced from "yellow grease"—used fryer oil that restaurants and food manufacturers send off for recycling—or from rendered animal fat. The heated fat is mixed with methanol and a catalyst (usually lye or potassium hydroxide) to yield biodiesel, together with some methanol and glycerin.

It's an efficient process; burning biodiesel produces more than three times the energy used to make it. (In contrast, ethanol manufacturing uses almost as much energy as is produced by the end product.) And the byproducts of biodiesel production are valuable: Glycerin can be refined and sold for use in food, pharmaceuticals and soaps; leftover crushed soybeans or canola seeds are sold as animal feed.

After testing and quality control, biodiesel is shipped to distributors, who blend it with regular diesel fuel for sale. Fuel blends are designated similarly to ethanol blends, with B2 being 2 percent biodiesel, all the way up to B100—pure biodiesel.

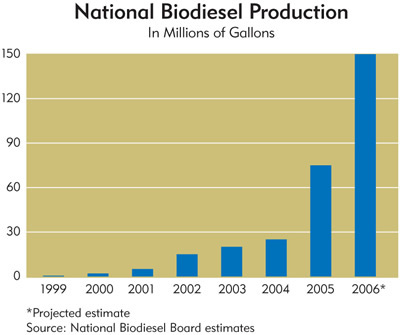

The escalating price of oil in the past two years has been a driving force in the national surge in biodiesel production. As recently as 1999, total U.S. production was about half a million gallons. Production increased to 25 million gallons in 2004 and then tripled in 2005. In a February survey by the U.S. Department of Energy, the price of a gallon of B20 in the Midwest was $2.51, close enough to the diesel price of $2.48 to bring in many consumers on the margin who want to use the fuel because of its perceived benefits.

Ken Astrup, manager of the Dakota Plains Cenex co-op in Valley City, N.D., which sells more than 400,000 gallons of biodiesel a year, says the fuel is especially appealing to farmers. "A number of them [use] it just because they believe in supporting their own product," he said. In July, Dakota Plains was selling biodiesel blend for the same price as standard diesel.

In addition to its favorable energy yield, biodiesel boasts other environmental plusses. A gallon of B20 emits 15 percent less carbon dioxide, which contributes to global warming, than a gallon of standard diesel. The fuel also produces much less particulate air pollution when burned, which has led some local governments to consider using it in buses and city vehicles to improve urban air quality.

Nelson, the country star behind the Farm Aid concerts of the 1980s, has capitalized on both farmer pride and environmental consciousness, marketing his own brand of B20 called BioWillie at truck stops around the country.

But there are other reasons to burn biodiesel besides its price and environmental benefits. It's an excellent engine lubricant—a key advantage over petrodiesel, thanks to federal regulations effective since July that limit sulfur in diesel to 15 parts per million. The previous limit was 500 ppm—a marked reduction from a 2,000 ppm ceiling just a few years ago.

Removing sulfur from diesel not only incurs extra expense, but it also sacrifices lubricity, crucial for proper engine performance. Adding as little as 1 percent biodiesel restores that lubricity. Other fuel additives serve the same purpose, but given biodiesel's favorable price, producers expect to see demand for the fuel increase even more.

Pay at the pump, or on April 15

The new sulfur regulations, which enhance the competitiveness of biodiesel, are just one example of governmental action that has given biodiesel a fighting chance in transportation markets long dominated by oil.

The biggest boost for biodiesel is the federal tax credit included in the 2005 energy bill. Modeled on a similar tax credit for ethanol, the credit takes the form of a per-gallon write-off for biodiesel blenders. For fuel produced from recycled grease, the credit is 50 cents; if it's produced from fresh vegetable oil, the credit is $1. This is effectively a subsidy to oilseed farmers, since yellow grease is cheaper and would be the feedstock of choice for most producers otherwise.

The effect of the credit on biodiesel prices isn't clear, since it is indirect. The credit effectively lowers the cost of the fuel to distributors, which in a competitive market should reduce the price of blended fuel at the pump. But biodiesel prices actually rose after the credit went into effect, because of demand for limited supplies of biodiesel as a substitute for increasingly expensive standard diesel. It's an open question whether biodiesel prices would have increased even more without the tax credit.

But the credit clearly provides a strong incentive to producers. Because Dakota Skies didn't break ground until after the credit was in place, it's hard for Dobrinski to gauge the market for his product without it. "Put it this way, we could have probably made it work, but I don't know whether we would have been able to find any investors," he said. "So I would say it's huge."

There's one catch with the tax credit: It's set to expire in 2008. Although legislation to extend the credit has already been introduced by some members of Congress, including Rep. Earl Pomeroy of North Dakota, the possibility looms that the subsidy could end, making biodiesel less attractive.

If the credit is allowed to expire, biodiesel may lose much of its competitive edge, but the nascent industry would still probably survive. It's true that a surge in national production (see chart) has come during a period when the fuel was federally subsidized; biodiesel received a different subsidy designed to encourage production from 2001 through 2005. But not all of that huge increase in production was subsidized, and the unsubsidized portion—about 20 percent—still represents a production increase over previous years.

The bad news for district farmers is that without the tax credit, yellow grease will become the cheapest source of biodiesel, due to its availability and low price. So without the $1 tax credit working in their favor, soy and canola farmers lose market share, and biodiesel contributes less to their annual income.

For the most part, state government in the district has not heavily subsidized biodiesel, restricting its support to grants for research and development and plant construction. The exception is Minnesota; the state has put its weight behind biodiesel by requiring that most diesel fuel sold in the state contain at least 2 percent biodiesel.

Effective last September, the biodiesel mandate is a primary reason two large plants opened in the state, making it the nation's largest producer of the fuel. "It was very important," said Tom Kirsting, commercial manager at Minnesota Soybean Processors in Brewster. "It gave some validity to biodiesel as a fuel, and helped establish a local demand for the product."

The mandate, which was briefly suspended last winter after truckers complained that biodiesel gummed up fuel filters, creates a built-in demand for about 17 million gallons a year. Without this law, in-state demand for biodiesel would presumably be much lower.

A large indirect subsidy to biodiesel producers comes in the form of crop support programs, which show no signs of going away. From 1995 to 2004, soybean farmers received an average of more than $1.3 billion a year in subsidies. Canola, which by comparison makes up a tiny share of the total oilseed market, received about $17.3 million per year.

Since subsidies depress crop prices, they also reduce the market price of biodiesel, although it's uncertain by how much. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that feedstock accounts for 86 percent of the cost of producing biodiesel, so any reduction in crop prices can be significant.

Warning signs ahead

Apart from public policy issues, market factors also have a bearing on biodiesel's prospects. These market conditions and constraints are interrelated, making it difficult to predict how quickly the industry will grow and when (or if) the fuel will reach its full potential.

The most obvious market shift that would slow biodiesel's momentum is a decline in the price of oil. It's reasonable to look at biodiesel production, note how it's risen with soaring oil prices and conclude that if oil prices return to pre-2004 levels, then so would biodiesel production.

Certainly, a number of biodiesel producers would be in trouble if petrodiesel prices dropped significantly. However, it's estimated that biodiesel would remain competitive as long as crude oil prices didn't fall very far below the current level (about $75 per barrel in July). "If crude oil is in that $50 range, then biodiesel makes sense at today's market price for canola and soybeans," said Dale Enerson, economist for the North Dakota Farmers Union. "Of course, if we get back to $30-a-barrel crude oil nationally, then neither ethanol nor biodiesel is competitive without subsidies."

Such a decline in oil prices is unlikely; most energy analysts don't see the price of petroleum coming down dramatically in the foreseeable future. Moreover, there's now an established market for the fuel that includes socially conscious consumers and diesel producers who value it as a lubricity agent.

Another potentially serious limiting factor on industry growth is rising crop prices due to supply constraints. Most vegetable oil is used for food, so biodiesel producers would have to pay a premium to divert it to biodiesel plants. At recent production levels, there's enough surplus oil on the market to keep prices low, but some economists predict soaring soybean prices as soy biodiesel nears 500 million gallons, enough to require almost 19 percent of current soybean oil production.

A recent study by USDA economists tried to divine the effects of the 2005 energy bill on crop price movements. Encouraged by subsidies, ethanol production is roughly 50 times that of biodiesel, at some 4 billion gallons in 2005. Grain byproducts are also generated by ethanol and used as livestock feed, and the study predicts that ethanol byproducts will reduce the demand for traditional soybean meal as livestock feed, resulting in lower soybean prices and production. If the USDA analysis is correct, the price of soy biodiesel should climb as its increasing production puts pressure on tighter supplies of soybean oil. But the complex interplay of market factors for different commodities means it's tough to make a firm prediction.

A few other market conditions pose a threat to the industry's continued growth. One is the refusal of farm equipment manufacturers to honor warranties if blends higher than B5 are used, because of uncertainty about the harmful effects of biodiesel on engines.

This uncertainty may have been compounded by Minnesota's troubles with biodiesel last December. It isn't known for sure what caused the clogged fuel filters on trucks; two leading candidates include improper blending at low temperatures and dirty diesel—caused by the refining crunch after the Gulf Coast hurricanes—aggravated by biodiesel's action as a solvent. But the episode cast doubts on the fuel's technical merits.

If those doubts remain, it may be hard for the industry to take off. "If they're not willing to go above a 5 percent blend on the warranty, I don't think you're going to see the huge growth in it, because farmers aren't going to take that chance," Astrup said.

Don't bet the farm on it

Any new market for crops is good news for farmers, but the district is unlikely to see a rural renaissance based on biodiesel in every tank. A look at the numbers helps to explain why.

The National Biodiesel Board estimates that if all the current and proposed projects in the country get built, they would be capable of producing 1 billion gallons of the fuel a year. A federal biodiesel mandate (some members of Congress have proposed requiring U.S. vehicles to burn 2 billion gallons annually by 2015) would certainly stimulate demand for that much biodiesel.

But Tiffany, at the University of Minnesota, believes that a lower production ceiling is more realistic. "If we just had a low-blend strategy for the whole country, maybe we could use about 500 million gallons of biodiesel [annually]," he said. Pushing production beyond that level risks driving up prices for soy and canola, thereby raising production costs and making biodiesel derived from fresh oil less competitive, even if the federal tax credit is renewed two years from now.

If demand for biodiesel takes off, producers are likely to turn to yellow grease as their preferred feedstock. Most recycled grease goes unused, and prices are lower and more stable. So grease renderers, not farmers, are in a better position to capitalize on any long-term growth in biodiesel usage.

The same economic constraints will likely prevent biodiesel from weaning the country of its dependence on imported oil. Even if nationwide biodiesel production rises to 1 billion gallons annually, that represents only 2 percent of diesel consumption in 2005.

Biodiesel's limited horizons raise the question of whether the fuel is worth subsidizing. Compared with other energy and agricultural subsidies, the cost of the federal biodiesel tax credit is a drop in the bucket, but because it's indexed to consumption, the subsidy will grow with biodiesel output.

All of this is not to say that biodiesel doesn't have a bright future in the district. Fundamentally, biodiesel is an effective, environmentally beneficial motor fuel that many consumers want to use. It provides farmers buffeted by low commodity prices with an additional market for their crops. Equally important, it gives those with an entrepreneurial bent the opportunity to add value to their produce, as in the case of the Minnesota Soybean Processors cooperative in Brewster.

Even if biodiesel won't eventually provide a market for all the soy and canola farmers can grow, or displace regular diesel from the nation's gas tanks, it's likely to continue to grow, with or without subsidies.

Tiffany pointed out that the fuel still has a long way to go before production hits a plateau. His conservative projection of 500 million gallons a year, based on finite amounts of feedstock, is five times this year's estimated production. "Biodiesel's just getting started in this country," he said, noting that the European Union produces more than 500 million gallons a year.

Joe Mahon is a Minneapolis Fed regional outreach director. Joe’s primary responsibilities involve tracking several sectors of the Ninth District economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, energy, and mining.